Health & Medicine

We need to talk about chlamydia

More than a century ago, Melbourne was at the forefront of measuring the spread of syphilis using principles which remain relevant today as the disease makes a comeback

Published 31 March 2019

Congenital syphilis has re-emerged as a problem in Australia, with health authorities now urging pregnant women to get tested for the disease. Far from being eradicated, syphilis has been on the rise steadily in Victoria since 2002, almost a century after Australia’s anxiety about the spread of syphilis reached its peak.

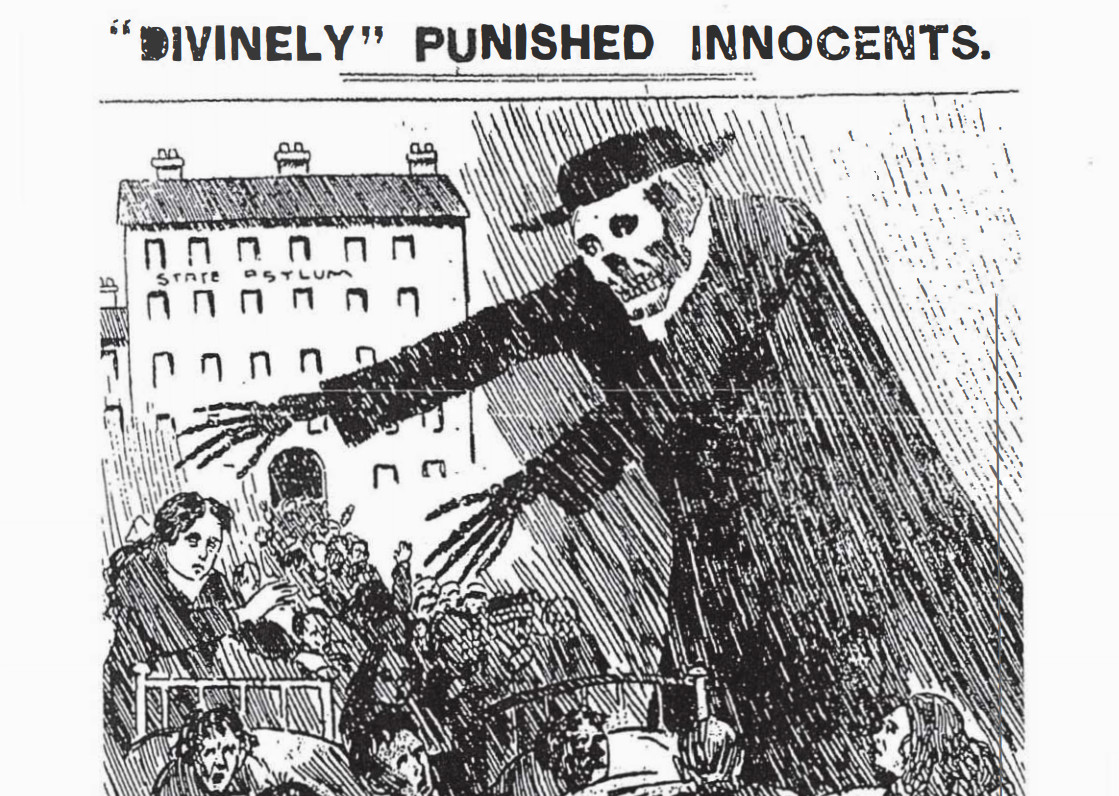

Back in the early 20th Century, newspaper headlines like The Social Evil and The Menace in our Midst provoked fear about a rising tide of immorality, and about infection of the innocent – such as co-workers who shared blow-pipe equipment in a glass factory or young women kissed by an infectious young man during a party game.

A sexually transmitted disease, syphilis spreads through skin-to-skin contact during unprotected sex or is acquired congenitally when a pregnant mother with syphilis infects her unborn infant through the placenta.

But 100 years ago, the mechanics of the infection were poorly understood and symptoms were often misdiagnosed as another disease or condition.

THE DIAGNOSTIC BREAKTHROUGH

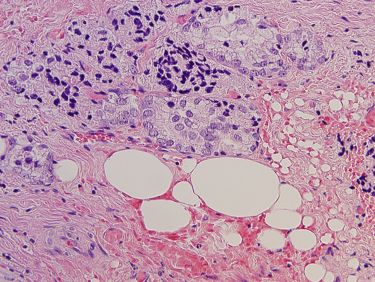

In 1905, the discovery of spirochete Treponema pallidum - the bacterium that causes syphilis - allowed for the microscopic examination of skin or mucous membrane lesions that identify the early stages of syphilis.

Health & Medicine

We need to talk about chlamydia

Just a year later, German bacteriologist August Paul von Wassermann and his colleagues designed a test that examined biomarkers in the blood following damage by the infection.

This was a giant leap forward in syphilis diagnosis but Wassermann’s test had limitations, as it also produced a positive result to a number of diseases uncommon in Australia as well as the commonly found scarlet fever and acute diabetes. For the test to be useful, a doctor needed to firstly exclude the presence of these other diseases, so a positive test result could be interpreted as a sign of syphilis infection.

A negative result didn’t necessarily guarantee a person was syphilis free because the biomarkers were not always present in the first few weeks of infection or in the very last stages of syphilis, so test results needed to be interpreted with this in mind.

THE MELBOURNE EXPERIMENT

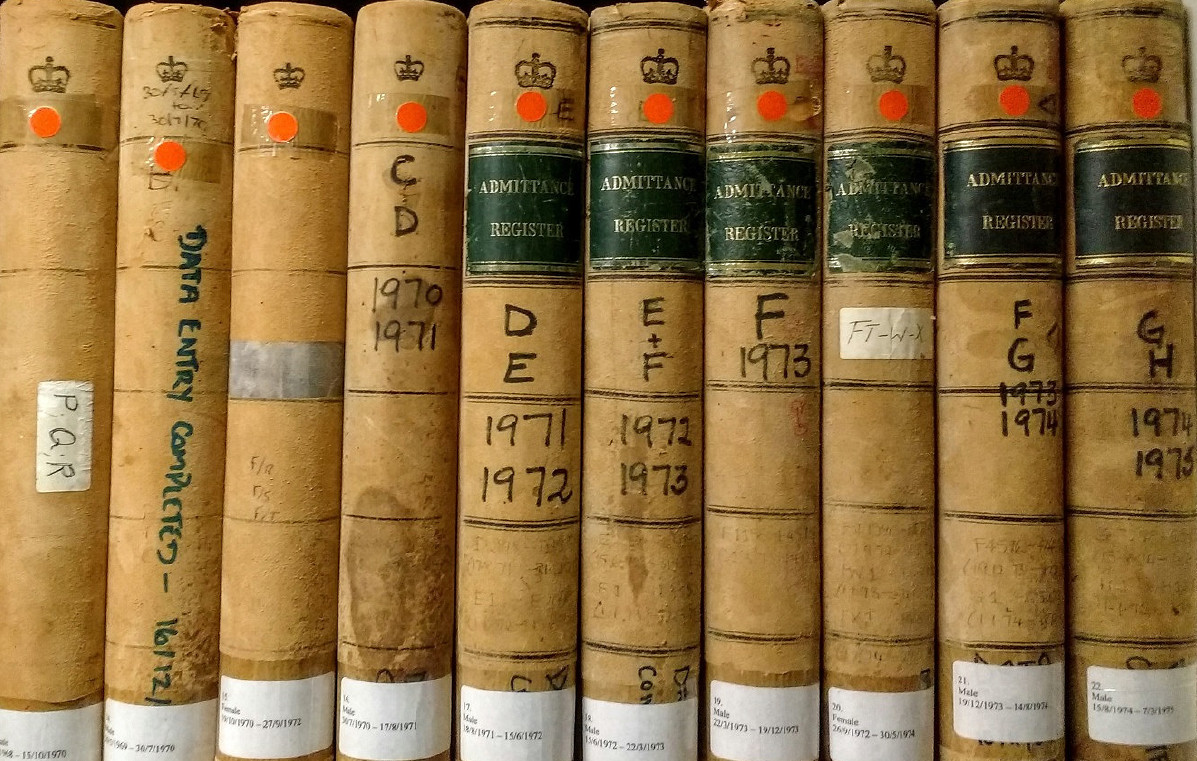

The Melbourne Experiment, which began in 1910, was claimed to be the world’s first scientific collection of community-based syphilis data. Up until then, most data collection had been haphazard.

For example, in 1904, President of the now superseded Australasian Medical Congress, Sir Harry Brookes Allen, performed 100 consecutive autopsies at the Royal Melbourne Hospital looking for evidence of syphilis.

Health & Medicine

Why is no-one talking about safe sex for the over 60s?

He reported clear signs in 34 cases, “doubtful signs” in 19 cases, and one case “open to suspicion”. But while Sir Harry was investigating syphilis as a cause of death, these cases were not representative of those living with, and potentially transmitting, the disease.

At the Australian Medical Congress in 1908 it was noted “we have no statistical basis for statements regarding the prevalence of syphilis and can only rely on our own experience”.

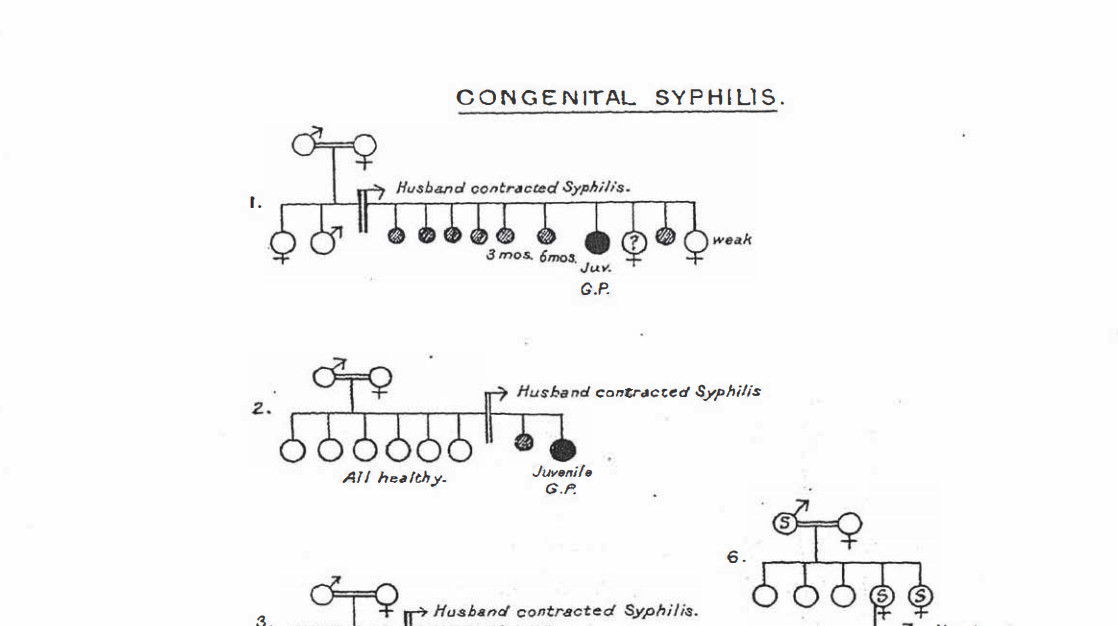

Eye and skin doctors, as well as doctors who saw children, were “profoundly impressed both with the prevalence of the disease, and especially with the gravity of its remoter manifestations”. They saw eye problems, blindness and a variety of general medical conditions which they believed were a result of, or magnified by, congenital syphilis.

Pathologists also noted evidence of syphilis in many autopsies but had mixed opinions on its prevalence. On the other side of the debate were physicians and surgeons who viewed the prevalence of syphilis as “not so grave”.

But the rates of miscarriage, stillbirth, and deaths of children thought to be caused by syphilis fuelled concerns of many about the strength and vitality of the Australian population.

THE STIGMA OF SYPHILIS

Children with signs of syphilis were over-represented at the Royal Children’s Hospital, according to paediatrician Dr P.B. Bennie, with very few in the mid-1890s but an increase of around30 per cent only a decade later.

Health & Medicine

Prostate cancer: Starving out the enemy

He noted that any child with a syphilitic parent seemed to be less resistant to disease than children born without ‘taint’, and it was believed that around 10 per cent of all children in Melbourne had syphilis.

But hospital statistics were of no value in determining syphilis prevalence because the stigma attached to the disease was so great that it was rarely included in a patient’s medical record.

Community-based data collection was needed.

On 1 May 1910, medical practitioners in Victoria received a letter from Mr B. Burnett Ham, Chairman of the Board of Health. It stated that syphilis would be proclaimed an infectious disease from 1 June 1910 to 31 May 1911 for those living within a ten-mile radius of the General Post Office.

This meant that during that year, anonymous blood samples of any cases of certain or doubtful syphilis had to be sent to the Board for a Wassermann test, along with details of the patient’s symptoms, sex and age.

Doctors were also asked to send notifications of mothers who may have given birth to a child with syphilis, suffered two antenatal deaths, or lost three children under the age of five. One shilling and sixpence was paid for each notification.

ADDING TO THE GLOBAL SYPHILIS PICTURE

In using the Melbourne Experiment to determine prevalence of disease, assumptions were made that people with syphilis would seek treatment and that a doctor would correctly suspect syphilis.

It’s now impossible to know whether the approximately one-third of doctors in the catchment area who did not notify cases, had none to notify or were not keen to participate.

Health & Medicine

Protecting the world from the threat of pandemics

In an extraordinary effort to maintain test quality, University of Melbourne medical graduate and bacteriologist, Dr Konrad Hiller, conducted every Wassermann test himself. Results were reported on a four- point scale from clearly positive to clearly negative. Only ‘true’ – or clearly positive – reactions were counted. He conducted 5,500 tests and 1,900 gave a clear reaction to the test – which enabled an estimate of the severity of the syphilis problem in Melbourne.

At the 1911 Medical Congress, Mr Ham stressed that control of syphilis required separation of the moral aspects from the medical. There followed a number of pioneering attempts to achieve this through a public education campaign that included the National Council of Women as advisors, voluntary inpatient treatment, night clinics and, ultimately, legislation.

The Melbourne Experiment was reported internationally and was presented to the 1913 British Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases.

The Commission, though, rejected the idea of compulsory notification, arguing that early diagnosis, better treatment and education were more essential and that compulsory notification might prevent people from seeking treatment.

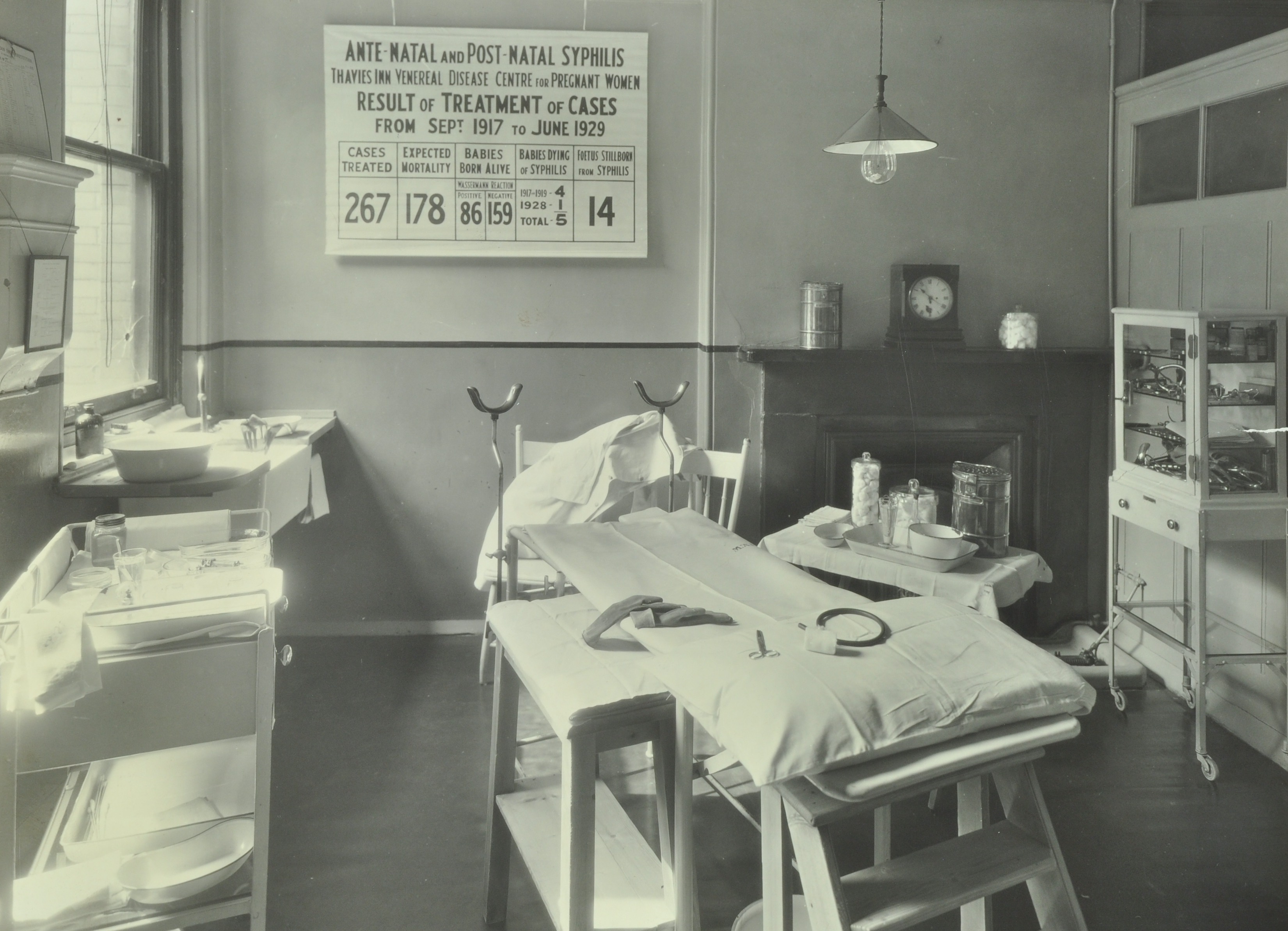

Despite this view, syphilis surveillance was adopted in Australia in 1917, Sweden in 1918, Canada in 1924, England, Scotland and Wales in 1937, France in 1942, Belgium in 1945, Ireland in 1947 and the US in the late 1940s.

More than a century on from the Melbourne experiment, monitoring these kind of disease trends is standard practice. And current surveillance of syphilis shows it’s an increasing problem in Australia – with an outbreak last year spanning three states and a territory.

Data collection remains the first step in disease prevention. While today’s infection rates are lower than last century, the rising rates are concerning. Both then and now, understanding the behaviour underpinning syphilis transmission is a major challenge to keeping those numbers down.

This work was conducted during Professor Meredith Temple-Smith’s residency at Fondation Brocher in Switzerland.