Sciences & Technology

Q&A: Victoria’s monster mosquito explosion

A mosquito trap that could significantly reduce egg numbers may be the answer to controlling mosquito-borne diseases – like the Buruli ulcer – in Victoria

Published 1 February 2024

Mosquito-borne diseases like dengue and Japanese encephalitis may feel like far-distant nightmares for many Victorians.

Here, the warmer summer months coinciding with the mosquito season are more synonymous with backyard BBQs and backyard cricket than the smell of tropical strength repellents and mosquito coils.

But in recent years, climate change has brought higher temperatures, higher humidity and extreme rain events to the south that’s increasing the risk of mosquito populations exploding.

And with it, an increased risk of mosquito-borne diseases.

What’s more, changing climatic conditions are giving previously overlooked local mosquito species, like the Australian backyard mosquito (Aedes notoscriptus), a leg up.

Sciences & Technology

Q&A: Victoria’s monster mosquito explosion

Not only is this species the main vector for heartworms in dogs, it can also transmit some diseases to people. For instance, the backyard mozzie has recently been suspected of transmitting Buruli ulcer, a skin infection caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans.

As this summer’s rainfall events and high humidity present ideal mozzie breeding conditions, we should start to become more cautious in dealing with mosquitoes and treat them as something more serious than just a nuisance pest.

Typically, mosquito management in Victoria involves a combination of surveillance and control. Mozzies are collected regularly across Victoria in traps and screened for pathogens, which can provide early warnings of potential health risks to local communities.

Chemicals designed to control mozzies can target specific sites – either the larvae (larvicides) or adult mosquitoes (adulticides), but can also be applied over large areas, in a process known as fogging.

Physical control methods focus on seeking out and removing potential breeding sites for mosquitos – like standing water on public land – and can be adopted at a local scale.

Households can reduce backyard mosquito populations by removing standing water from plant pots, old tyres, tarpaulins, bird baths or any other containers, as well as ensuring that any screening covering water storage containers is intact.

Sciences & Technology

Dengue-blocking bacteria endure the heat

But, physical control methods and targeted chemical treatments will often miss hidden breeding sites like cracks in drainage pipes and inaccessible gutters where water can accumulate.

Additionally, chemicals that are used for fogging and that target adults can harm other insects like bees and butterflies that often provide benefits to gardens such as through pollination.

So, what other solutions are there that can tackle our escalating mozzie problem?

The Pest and Environmental Adaptation Research Group at the University of Melbourne is working towards an answer.

In a small-scale field trial in the backyards of outer Melbourne residents, our research group set out to demonstrate how a new type of mosquito control system, a product known as an In2Care station, could reduce Aedes notoscriptus mosquito numbers.

This, in turn, would reduce mosquito biting and help control the spread of Buruli ulcer.

And our preliminary trial was well received by locals and successfully reduced the mosquito population by around a half.

Sciences & Technology

Tracking the movement of mosquito stowaways

The best part about this method is the mosquitoes themselves do all the dirty work without any harmful effects to the surrounding environment.

The In2Care stations work through two active ingredients: a mosquito-specific growth regulator and a naturally occurring fungus.

The ingredients are transferred to a female mosquito when she enters the In2Care station to lay her eggs. It then harnesses the natural breeding behaviour of the mosquitoes.

When a female mosquito lays her eggs in a station, the growth regulator prevents any of her offspring from emerging as biting adults. The dying and decomposing larvae within the station create an even more attractive site for other mozzie females on the hunt for a good breeding site.

In the process of depositing her eggs, the female also picks up ingredients from the stations, taking them with her as she continues to search for additional breeding sites. These sites might include those that are inaccessible or hidden from people, like clogged gutters or storage tanks with cracked screens.

Once the mozzies lay their eggs there, they also spread the growth regulator which affects larval development and reduces the number of new mosquitoes. Then the second active ingredient – a natural fungus called Beauveria bassiana – kicks into gear.

This fungus, a natural insect pathogen found in soils worldwide, reduces biting behaviour in mosquitoes and, after a few days, the mosquitoes succumb to the infection.

Sciences & Technology

5 slightly disgusting facts about mozzies

This process overcomes the two main hurdles faced by current mosquito control methods in urban settings.

Firstly, the In2Care stations put the mozzies to work in delivering the growth regulator to hidden or inaccessible sites. Secondly, the effects on beneficial insects like bees are minimal because they are not in direct contact with the mosquito-specific In2Care stations.

People, pets, birds, and pond fish don’t suffer any negative impacts either - the growth regulator only affects insect larvae.

As our climate continues to warm and rainfall becomes more variable, we need to discover and test new environmentally friendly and sustainable ways of dealing with mosquito outbreaks and the diseases they can transmit.

Currently in Melbourne’s inner west, Buruli ulcer cases are on the rise.

This infection, caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans, affects the skin and soft tissue, causing the destruction of skill cells, small blood vessels, and underlying fat. The severity of the damage can be extensive if diagnosis is delayed.

Recently, research conducted locally has found evidence that the Buruli ulcer is transmitted from possums to humans though mosquitoes – with the Australian backyard mosquito emerging as the most likely culprit.

The Beating Buruli in Victoria teams’ latest publication provides compelling evidence to support this hypothesis.

Health & Medicine

Blood for science: Putting the bite on mosquito viruses

In tandem, our team is launching an expanded trial of In2Care stations starting in early 2024 which will continue until the end of the peak mosquito season in late April this year.

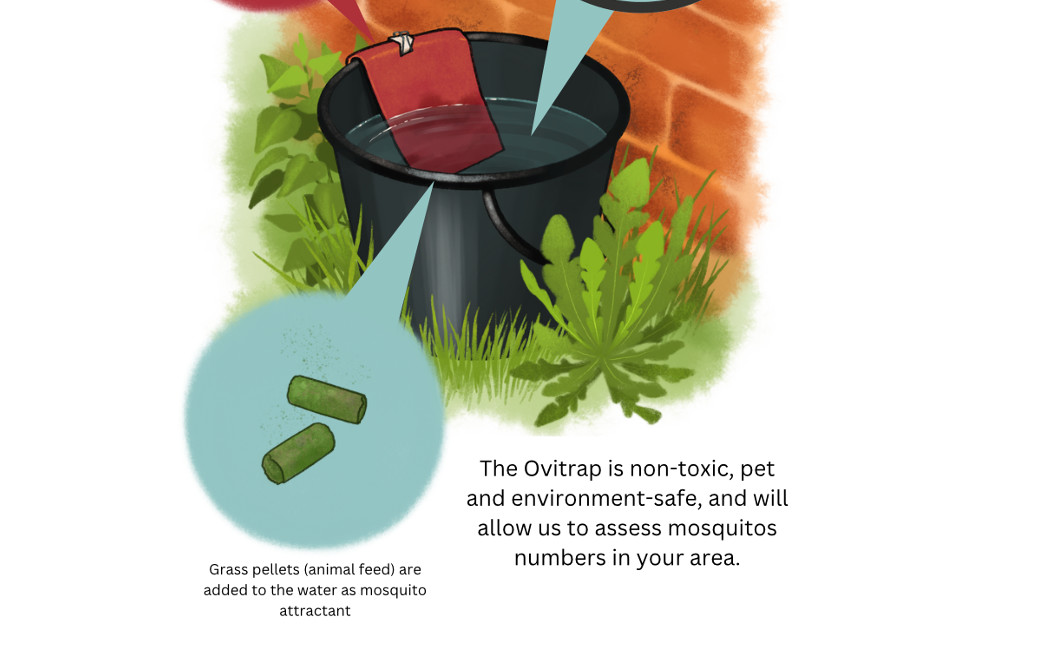

Monitoring traps (known as ovitraps) are already in suburbs thought of as Buruli ulcer ‘hotspots’ to evaluate the size of the current mosquito population there.

During the next phase of the project, In2Care stations will be deployed in public spaces and residential backyards.

So, if one of our research team knocks on your door in early February, please consider hosting one or two stations around your property. This not only supports our ongoing study but is also likely to reduce the mosquitos around your house and in the local area.

Your cooperation is crucial in combating the spread of mosquito-borne diseases like the Buruli ulcer and advancing our understanding of effective mosquito management strategies.

The In2Care station is a smart solution that minimises harmful outcomes on our already stressed environment.

And more innovations like this mean that we can enjoy our summer evenings (mozzie free) in the future.

Banner: Marianne Coquilleau