Sciences & Technology

Talking dirty: The conversation between plants and soil

Ethylene is famous as the chemical that tells bananas to ripen, but new research shows it also helps maintain plants’ circadian clocks

Published 20 October 2017

Each of us goes through a daily cycle. We wake up, spend the day eating, working and playing, and then we sleep. Messing with this cycle by not sleeping, doing shift work, travelling to a different time zone or living where there is 24 hours of light or dark can really interfere with our wellbeing and our long-term health.

Most plants have similar cycles. During the day, little solar farms in a plant’s leaves ‘wake up’ and convert sunlight and carbon dioxide to sugar through photosynthesis, then at night this system switches off. Many other plant processes follow a similar cycle, with some more active in the day, and some more active at night.

New research is shedding light on the impact of these cycles on plant aging processes, and vice versa.

The day-night cycle is regulated by what are known as circadian clocks. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Dr Jeffrey Hall and Dr Michael Rosbash from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, alongside Dr Michael Young, at Rockefeller University in New York City, for their work on uncovering the mechanism behind circadian clocks in fruit flies.

Circadian clocks are 24-hour cycles responsible for controlling basic biological functions in living beings like metabolism, blood pressure, sleep and hormone levels.

Plant signalling researcher Dr Mike Haydon, from the School of BioSciences at the University of Melbourne, says since the discoveries of Drs Hall, Rosbash and Young, there has been a lot of research into the health impacts of disruptions to our circadian clocks as we age.

“We know the clock changes as we age, and it has been implicated in metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity. However, we don’t know much about how the clock affects ageing in plants,” Dr Haydon says.

In plants, research has shown that environmental cues like temperature and sunlight regulate circadian cycles. However, put a plant in a dark cupboard, and many of these day-night processes continue. But how? Researchers like Dr Haydon are fascinated by this mystery.

“The earliest reported experiments demonstrating circadian rhythms in complete darkness were done in plants in the 18th century,” he says.

“These biological rhythms have evolved multiple times, in plants, animals and other organisms, so they are clearly important.”

Plain old sugar, or sucrose, plays a part.

“In humans, we know our circadian rhythm can be affected by when we eat, and in plants it’s the same,” says Dr Haydon.

“A few years ago my colleagues and I showed that sucrose (which is produced by photosynthesis) is required to maintain circadian rhythms in the dark.

“We then found that in continuous light, sugar can shorten the circadian rhythm, and these kinds of feedback loops help plants maintain the ideal cycle.

“But we didn’t really understand the mechanism behind this.”

Ethylene, known as the ‘ageing hormone’, is commonly produced by plants and is best known for promoting fruit ripening, but it also has important roles in growth and responses to pathogens or other stresses.

Plants release ethylene as a gas, which is why putting a yellow banana next to an avocado can help it ripen faster.

“Ethylene gas is a way for plants to communicate with each other, ensuring, for example, the fruit all ripen at the same time,” says Dr Haydon.

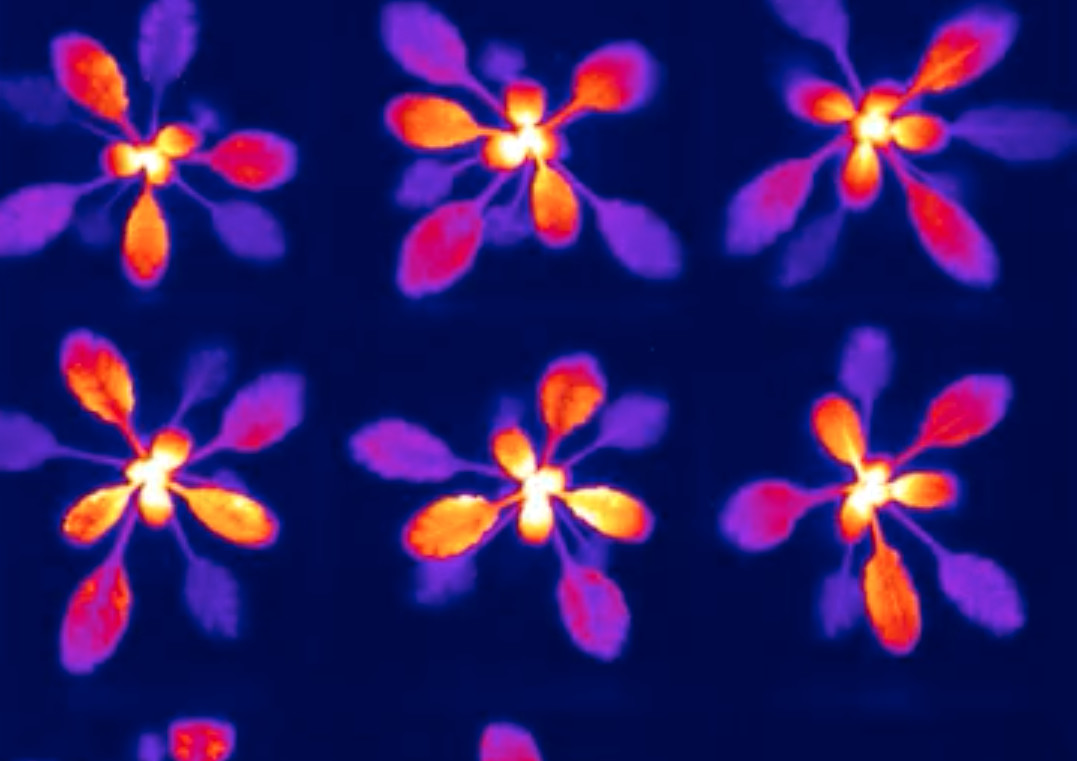

While exploring the genes and proteins that regulate the circadian clock in Arabidopsis (a small flowering plant related to cabbage and mustard), a research collaboration led by Dr Haydon and Professor Alex Webb at the Universities of Melbourne, Cambridge and York discovered that ethylene is one of the keys to maintaining the plant’s circadian rhythm.

The work was funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and is published in the journal Plant Physiology.

Sciences & Technology

Talking dirty: The conversation between plants and soil

“We knew that ethylene production follows the day-night cycle, but we didn’t know that it also feeds back in to help regulate this cycle,” says Dr Haydon.

“There is a well-defined network of receptor proteins and transcription factors that mediate ethylene signalling in plants. This ethylene signalling pathway promotes circadian rhythms by acting on the clock-regulating genes, GIGANTEA, which is also regulated by sugar.

“We found that ethylene reduced the circadian period, but this effect was blocked by sugar.”

Circadian clocks regulate the 24-hour cycles of plants, but Dr Haydon says there are other ‘clocks’ that respond to longer time-scales, like seasonal cycles, and these long-term ageing processes, which are heavily influenced by ethylene, could be impacted by disruptions to circadian clocks.

Health & Medicine

Scaring the daylights out of our body clocks

“By manipulating these we could fine-tune development rates to optimise crop yields or shelf-life,” he says.

“Bananas, for example, are cut green to reduce damage during transport and then shipped around the world. Once they reach their destination, they are often sprayed with ethylene to ripen them.

“Previous research has shown that vegetables and fruits depend on their circadian rhythms even after harvesting,” says Dr Haydon.

So this raises the question, should we store our fruit and veggies in the fridge, or should we allow them to maintain their natural day-night cycles out on the kitchen bench?

Dr Haydon’s advice is to leave your fruit and veggies out of the fridge.

“Even after they are cut, your veggies are still living plant cells. They are best kept as fresh and as close to their natural environment as possible.”

Banner image: Clock activity in Arabidopsis as visualised by a clock gene fused to the Firefly Luciferase gene / Laboratory of Plant Physiology