The complex cultural politics of writing fiction in ‘someone else’s language’

The work of author Ian Hideo Levy, the first Westerner to write literature in Japanese, questions the links between language, nation and ethnicity

Published 4 July 2025

When people cross national borders in areas such as politics and economics, it may not seem especially remarkable.

But when it comes to fiction writing, the decision to work in another language can prove confounding.

As American author Ian Hideo Levy has often remarked, much of the media attention he receives for writing in Japanese is not about the content of his work, but why he would choose to write in his non-native language.

Although there is a relative acceptance of authors who move from ‘peripheral’ languages to ‘major’ ones – from Salman Rushdie and Joseph Conrad to Vladimir Nabokov and Milan Kundera – the reverse can seem mystifying.

Hideo, named after a Japanese-American family friend, has lived in Japan for the past few decades and has produced award-winning fiction as well as essays and criticism.

Since his 1992 debut, A Room Where the Star-Spangled Banner Cannot Be Heard, all his work has been written in Japanese.

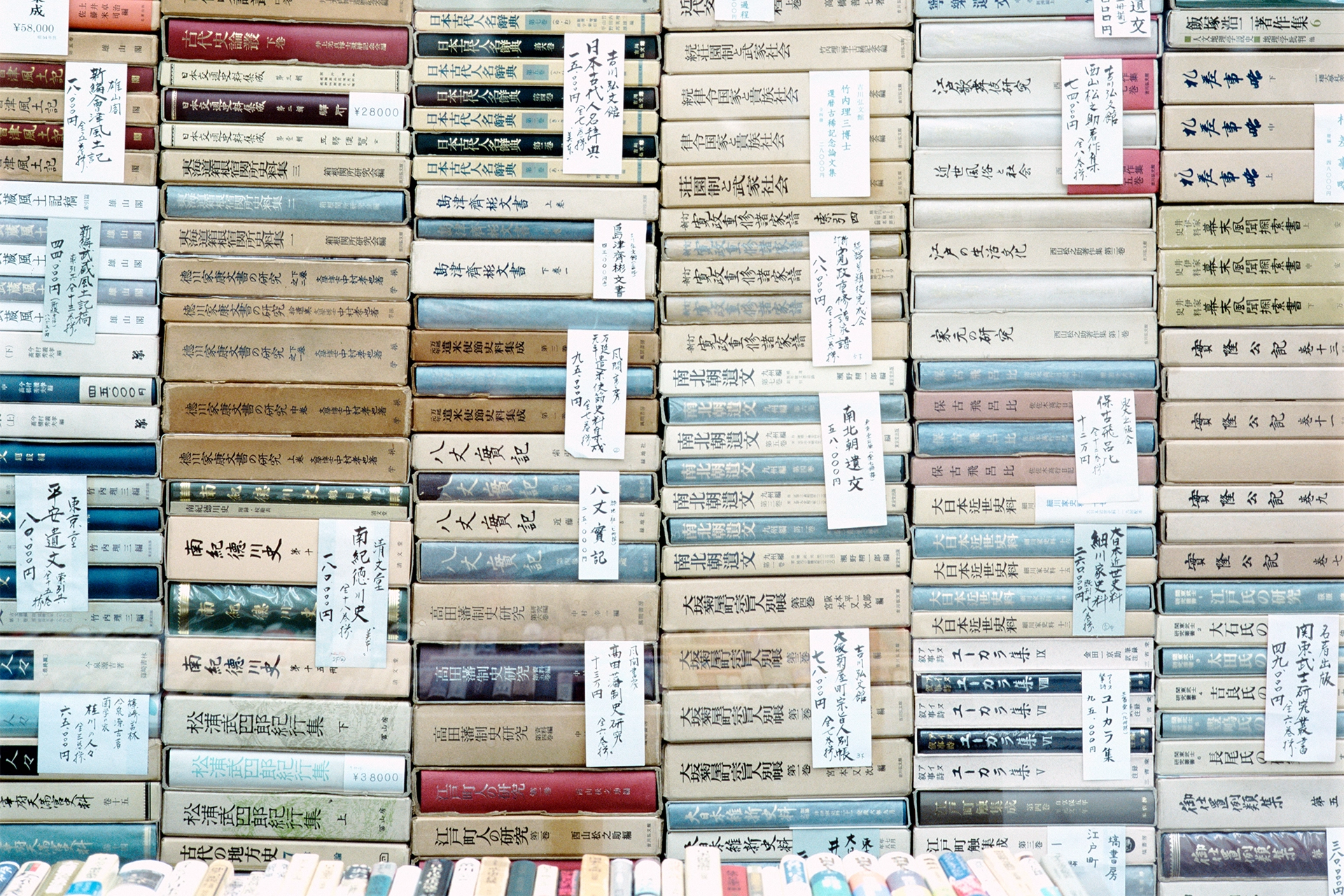

One example Hideo has often drawn upon in considering the separation of language from nation and race is the Man'yōshū, a seminal anthology of ancient Japanese poems.

One of the Man'yōshū’s poets, Yamanoue no Okura, was likely Korean.

For Hideo, this suggests something profound: if a non-Japanese person could be responsible for such canonical works of Japanese writing, why, in the contemporary era, are borders of linguistic and ethnic identity often erected around language, around who ‘gets’ to be identified with a culture, a language and a nation?

Over the last twenty-odd years, Hideo has written increasingly about the Chinese mainland in the Japanese language, further expanding the descriptive capabilities of the language and refusing to produce writing that can be easily categorised under familiar genres, such as journalism or travelogue.

During the publication of his debut, Hideo nominated the example of American sumo wrestler Konishiki, the first non-Japanese-born wrestler to achieve the sport’s second-highest rank, as an example of the pushback and exclusivity that can attend attempts by foreigners to participate in the cultural traditions of other countries.

As Hideo has noted, the question of relationship to place is bigger than national borders.

In his article Shinjuku no Man'yōshū (Shinjuku’s Man'yōshū) for the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Hideo writes:

I was told, by the Japanese around me, ‘You cannot be one of us; no matter how hard you try, it is racially impossible. You cannot possibly read, you cannot possibly understand.’ The more I received this message, the more I thought, ‘That’s not true’. A sense of resistance grew.

His most recent novel, Tenrō (Sky Road), takes place in Tibet and concerns an unnamed narrator who, struggling to accept his mother’s passing in a Washington nursing home, reflects on death and resurrection while travelling the Tibetan plateau, the ‘roof of the world’, with a Han Chinese friend.

The uncoupling of ethnicity and language found in the work of an author like Hideo involves some semantic difficulties: nihonbungaku, literally ‘Japan literature’, is often assumed to be synonymous with nihonjin sakka, or ‘Japanese author’.

Yet ‘Japanese author’ doesn't make sense for authors like Hideo or others who have, as Hideo has written, “not one drop of Japanese blood”.

The peculiarities of Hideo’s debut are difficult to translate into English since much of the weight of the original depends upon a (presumed) Japanese reader inhabiting its viewpoint, the ‘I’ of a non-Japanese character.

In Hideo’s 1998 novel Kokumin no Uta (Song of the People), the narrator, an American living in Japan, returns to the US to visit his mother and brother in Washington. He observes the country in a language that encounters America – and everything from its class and racial politics to the names of local streets and aspects of its popular culture – as if they belonged to a foreign entity, something he can only comprehend ‘in translation’.

Similarly, by using a mixture of different languages and perspectives, Hideo complicates the connections between language and culture in his 2005 novel Chiji ni Kudakete (Broken into Thousands of Pieces).

It tells the story of a translator of Japanese literature named Edward, estranged from his family after moving to Japan, who finds himself stranded at Vancouver airport en route to New York during 9/11 and unable to enter the US.

Autofiction and the shishōsetsu

Hideo’s work is often seen as belonging to shishōsetsu, the ‘I novel’, a form of autobiographical fiction that is generally understood as ‘pure literature’ (junbungaku), as distinct from speculative fiction.

The shishōsetsu can be compared to autofiction; both involve writing that is not strictly autobiographical but tends to include many elements directly traceable to the author’s life.

In the years since Hideo made his debut, there have been signs of cross-pollination between his work and others.

Arts & Culture

After 50 years, why Stephen King is still relevant

Iranian writer Shirin Nezammafi has written works of fiction in Japanese set entirely overseas and featuring characters with no connection to Japan. This act poses further, and potentially even more discomfiting questions about the role of language and representation in the choices an author makes.

A Home Within Foreign Borders

In a documentary from 2012, A Home Within Foreign Borders, Hideo makes an emotional journey to Taichung, Taiwan, to try and locate his childhood home.

His journey is accompanied by another non-native Japanese language author, Wen Yuju, who moved to Japan from Taiwan at age three and now writes essays and fiction in Japanese.

Yuju tells him, “What makes you stand out is that you use Japanese to express yourself. You have a Japanese-language existence.”

Toward the end of the film, Hideo’s conclusion offers a complement to Yuju’s description:

When all is said and done, this isn’t about Taiwan or China. It’s about what can be expressed, in today’s world, of a person’s relationship to place. That which has yet to find expression.

Whatever language he uses, whatever the place or history he writes about, Hideo seeks not so much to master Japanese but to encourage it to say things it has not said before. To let it speak to subjects it has not necessarily had the chance to speak with, and whose depiction might change the way that the language itself – and the way language more broadly – is perceived and understood.