Health & Medicine

Privacy and health: The lessons of COVID-19

Clinical decision support systems help doctors ‘do the right thing’ by their patients, but they can also be exploited – Australia needs to think about regulation sooner rather than later

Published 25 May 2021

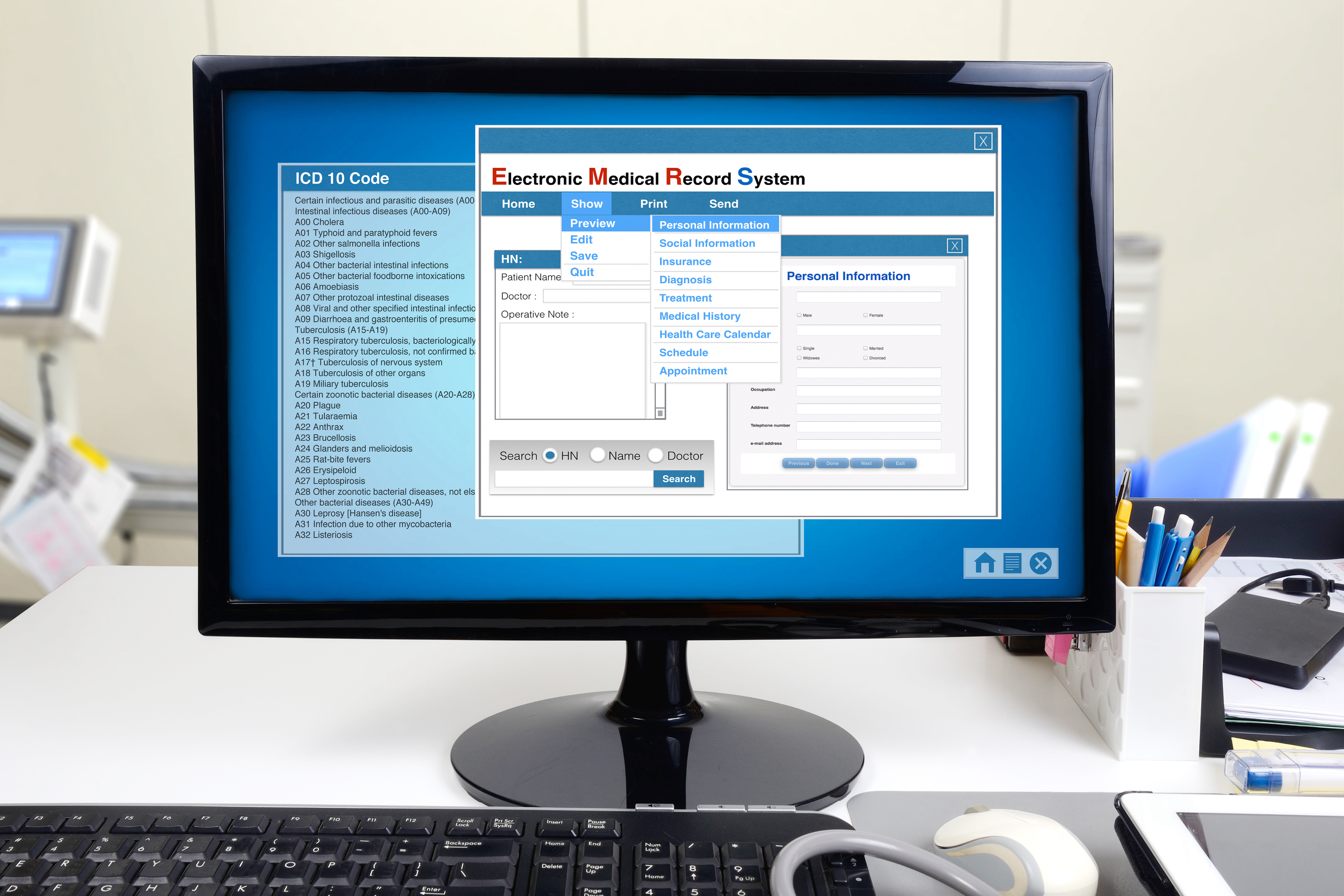

These days, most of us are aware of electronic medical records.

They are complex software systems made up of all sorts of confidential information like vital signs, notes about a patient’s symptoms, prescribed medications and test results, that are used by doctors to support patient care.

The general assumption is that by storing this clinical information in a digital format it can be easily reviewed at a later time, it allows for measuring and improving the quality of services, and can help scientists figure out which treatments work better than others.

Under these assumptions, they have been widely adopted both in Australia and internationally.

One of the frequently used tools in electronic medical records (EMRs) is called a clinical decision support system. These systems are smaller pieces of software, usually part of electronic medical records, that basically help clinicians ‘do the right thing’.

Health & Medicine

Privacy and health: The lessons of COVID-19

For example, it might be a pop-up that flags a potential medication allergy or lets the doctor know that the test they are ordering was already done very recently.

But, as with any technological innovation, clinical decision support systems can be exploited for unintended and unethical purposes.

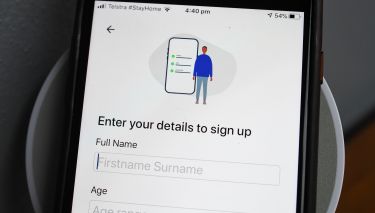

One way these tools are exploited is by implementing what’s been called dark interface design patterns. These ‘dark patterns’ exploit our cognitive biases and use mental shortcuts to trick us into making decisions that are more aligned to third party interests than to our own.

They are also remarkably common. Many of us will have come across dark design patterns on the web almost without realising it.

For example, when companies make signing up for a service extremely easy and seamless, but create hurdles to cancel your subscription – that’s a dark design pattern.

But these patterns have also been found in EMRs with potentially devastating consequences, and very few instances of this happening have been made public.

In 2020, while most of us were wrapping our heads around the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic, a US-based health information technology developer paid more than $US145 million to settle a lawsuit. The EMR company was accused of modifying a clinical decision support system to increase the likelihood a doctor would prescribe long-acting opioids to patients suffering from chronic pain.

Politics & Society

Information accessibility and the right to know

For years, experts have been advocating for better training and clearer guidelines to improve the way non-specialists identify and treat chronic pain. And that can be tricky. It’s a condition that can frequently go undiagnosed and have significant long-term consequences if not treated appropriately.

Clinical decision support systems designed to improve the identification and treatment of chronic pain have been part of the tools adopted by many health systems.

In this particular lawsuit, the EMR company was accused of colluding with a drug company to insert an additional option in a drop-down menu – offering clinicians an easier way to prescribe long-acting opioids.

While other items in the drop-down menu were supported by clinical evidence, this one wasn’t, but it was designed to look equal in importance to all of the other recommendations.

Changing the user interface – in this case the drop-down menu – meets the definition of a dark design pattern: it’s a change in the design that makes it easier to do things that do not align with the values of the user – in this case the clinician – or the values of the patient.

And the potential impact of something as simple as this on people’s lives is enormous.

A preliminary analysis provided by the EMR company found that this compromised system presented the altered recommendation during 21 million patient visits, affecting 7.5 million unique patients and almost 100,000 healthcare providers – all of this after only four months of operation.

Sciences & Technology

When tools for a health emergency become tools of oppression

The drop-down menu option remained until the spring of 2019. It generated more than 230,000,000 alerts and probably resulted in tens of thousands of unnecessary opioid prescriptions.

All of this during an epidemic of opioid abuse that has led to an estimated 500,000 deaths in the US during the last 20 years.

Dark design patterns have unfortunately become part of our internet landscape. They are ubiquitous and lure us into accepting cookies, signing up for things we don’t really want and spending far too much time online.

But dark design patterns in clinical software takes the problem to a new and dangerous level.

Most clinicians are probably not aware that these systems can be manipulated and, because they are not open to the general public, they are particularly hard to scrutinise.

Although this is only a single case in the wider landscape of positive outcomes from electronic health records, it must raise alarm bells over how important it is to design these systems carefully.

Currently, research and regulations are playing catch up – but they must do so in order to safely monitor the design and ethics of electronic medical records and clinical decision support systems – and prevent something like this from happening to Australian doctors and their patients.

Banner: Shutterstock