Arts & Culture

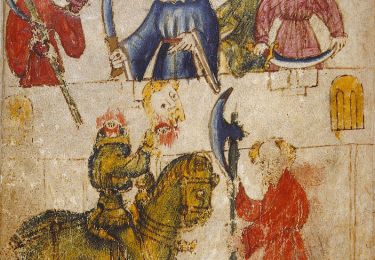

The poem behind the Green Knight

Boccaccio’s fourteenth-century masterpiece, now a Netflix series, shows the universality of human responses to a pandemic (along with some sex)

Published 24 July 2024

For anyone versed in medieval European history, the new Netflix adaptation of a 700-year-old story about a group of noble youths seems a timely endeavour.

Florentine poet and scholar Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) composed the 100 short stories collectively known as The Decameron (lI decamerone) in a lull of the plague that came to be known as the Black Death, which arrived in Italy on trade ships from the East in late 1347.

Written in an accessible Tuscan vernacular, the stories are often highly witty, satirical and outright bawdy, but they also provide an engaging window into life at the time.

The stories’ introduction, however, is altogether more sombre.

It provides one of the most detailed eyewitness accounts of the terror of the plague in the early modern world.

This introduction has been on my history students’ reading lists for many years, but never did it resonate as much as it did in the last few years. COVID-19 gave students a chance to reflect with some surprise on the universality of the human responses to our extreme fear of infectious disease.

Just as we saw during the depths of COVID, in the 1300s pandemic there were some who partied on recklessly, those who took to paranoid ascetic withdrawal and others who showed remarkable selfless humanity.

Arts & Culture

The poem behind the Green Knight

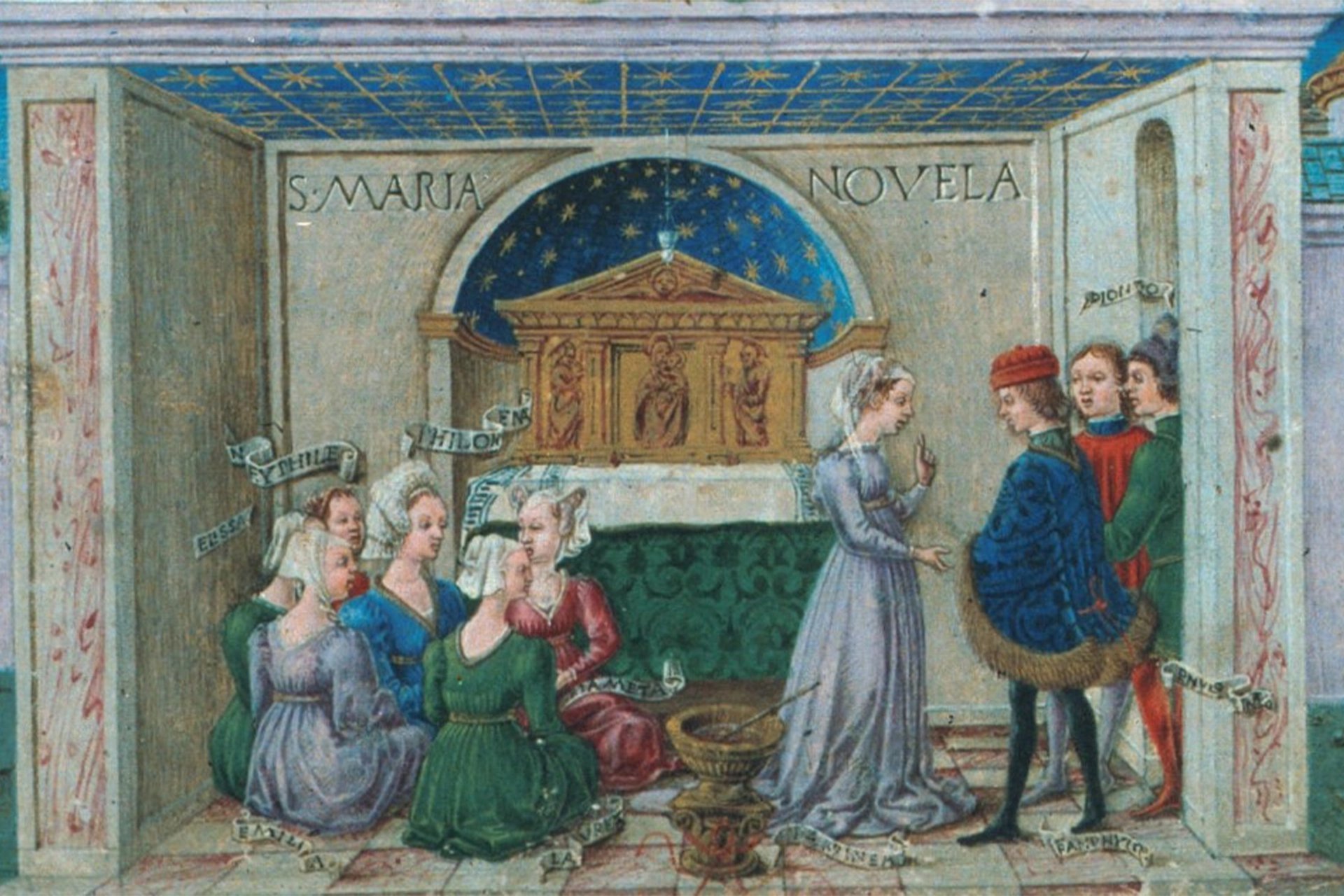

Against this plague backdrop, Boccaccio introduces seven supposedly unimpeachable maidens, aged between 18 and 27, “of noble birth, gentle manners, and a modest sprightliness”.

They have gathered in a sacred setting, the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

After the celebration of the Mass, they remain a while reflecting on the misery they have witnessed, the relatives and friends they have lost, and find themselves careworn survivors in need of a restorative break.

While this wealthy brigata have a selection of country estates to choose from, they decide to retreat to a delectable villa in Fiesole in the foothills of Florence.

Boccaccio is at pains to emphasise that this was not an indulgent quarantine locale, as some have incorrectly described it, but a place of recovery for a group who have been in the thick of the terror tending those near and dear to them.

Indeed, their eldest and chief instigator, Pampinea, declares that no one could accuse them of running away. They have spent the year caring for all their relatives who are now either dead or have left the city:

Our kinsfolk being either dead or fled in fear of death … we are left alone in our great affliction.

Worried about causing possible scandal as a group of genteel unaccompanied women, they decide to invite as chaperones three male friends and kinsmen of some of them, “as gallant as they are discreet”, who serendipitously arrive in the church.

As soon as the brigata arrives at their chosen villa, they feel the need to impose order on their days – hence Pampinea’s suggestion for each of them to tell one tale each day on a set theme, repeated over ten days – a total of 100 tales.

Health & Medicine

What disaster movies can teach us about coping with COVID-19

At the end of the ten days, they decide the time has come to return to their lives in the city. The period of respite is over.

In the 21st century, at the onset of worldwide lockdowns, Boccaccio’s narrative device received renewed attention and a new genre of what is now known as ‘lockdown fiction’ emerged.

In 2020, the New York Times Magazine launched its ‘Decameron Project’, commissioning twenty-nine short stories “to help us try to understand this moment”.

The project resulted in a special issue of the magazine, a website, and a book, The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic, with an impressive line-up of contributors (re-issued in paperback in 2022 with a new main title Stories from Quarantine).

As the magazine emphasised in bold: “When reality is surreal, only fiction can make sense of it”.

On 8 March 2020, the first day of lockdown in Venice, local historian Alberto Toso Fei, on his popular Facebook, YouTube and Instagram ‘Venezia in un minuto’ (‘Venice in a Minute’), began a telling of Venetian tales each night at 11pm, Decamerone Veneziano.

Initially intended as a telling over 10 days, he found himself moving to a monthly tale and only concluded his self-imposed task in December 2021.

Boccaccio’s stories have not appeared on screen since 1971 when Italian film maker and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) filmed a loose rendition of twelve of the stories as the first of what became known as his Trilogy of Life films.

The other two were The Canterbury Tales in1972 and the Arabian Nights in 1974.

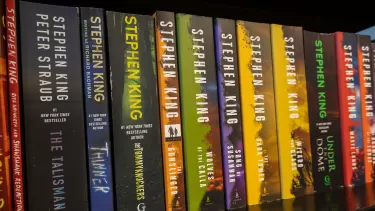

Arts & Culture

After 50 years, why Stephen King is still relevant

Pasolini, an avowed Marxist, did not try faithfully to recreate Boccaccio’s stories but rather to throw a critical lens on his contemporary world.

He explored the exploitation by the ‘haves’ in the north of Italy against the ‘have-nots’ in the south, as well as his country’s bourgeoisie and their post-war obsession with American-driven consumerism.

Pasolini also emphasised the sexual exploits in Boccaccio’s tales, ostensibly to recreate a lost world of innocent sexuality freed from man-made constraints.

But, to date, no one has thought to focus not on the tales but on the ten youths who are their narrators.

Enter Netflix and the creators of this forthcoming series, Kathleen Jordan and Jenji Kohan.

This is a nice conceit, but anyone expecting a recreation of the mores of mid fourteenth-century Florence will be in for a rude awakening.

Expect instead a “wine-soaked sex romp in the Italian countryside” – “like ‘Love Island’ but back in the day”.

Jordan admits that Boccaccio himself would be “confused” at their rendition.

For Jordan and Kohan the setting provides instead an opportunity to highlight the behaviour of those, like former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who partied on while those under their care suffered, and have a rollicking Bridgerton-esque time of it in the doing.

Though his fictional narrators remained virtuous, Boccaccio hinted at the possible sexual yearnings of his audience.

He tells us that his intended readers were “gentle ladies” who are stuck in their chambers and yet who “betwixt fear and shame, they harbour secret fires of love, and how much of strength concealment adds to those fires.”

So if you too find yourself stuck in your chamber harbouring secret fires of love, then perhaps this new adaption will be just the series for you.