The demon dance: A modern reimagining

VCA dance students are recreating a seminal work from the founder of Australia’s first modern dance company, nearly 90 years after it was first performed in London

Published 9 August 2017

Early modern dance is associated with floating scarves and light leaps and bounds. However, after the First World War those innocent reveries were only one form of dancerly expression.

The impact of modern industrialisation and political revolutions in 20th century Europe highlighted the conflict between man and machine, and for many the machine symbolised the engine of a new moral and social order.

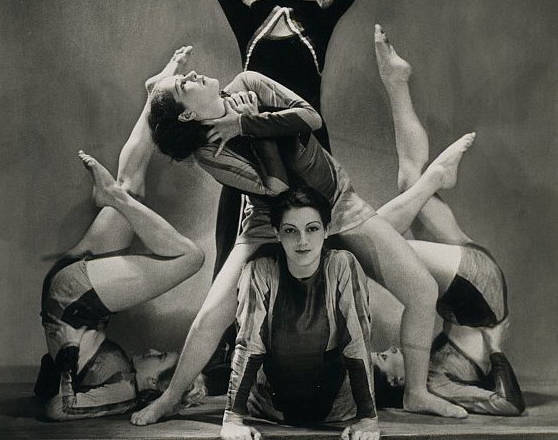

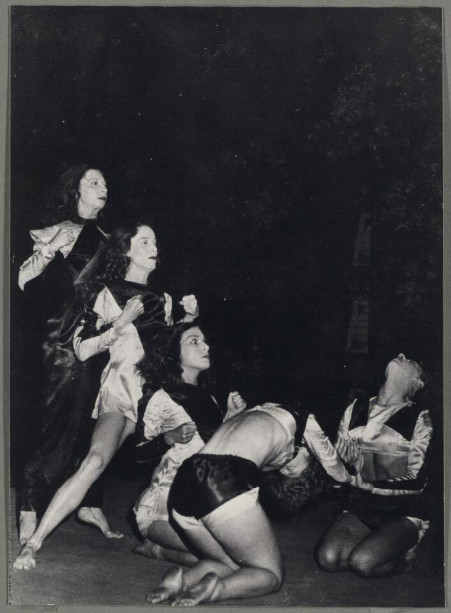

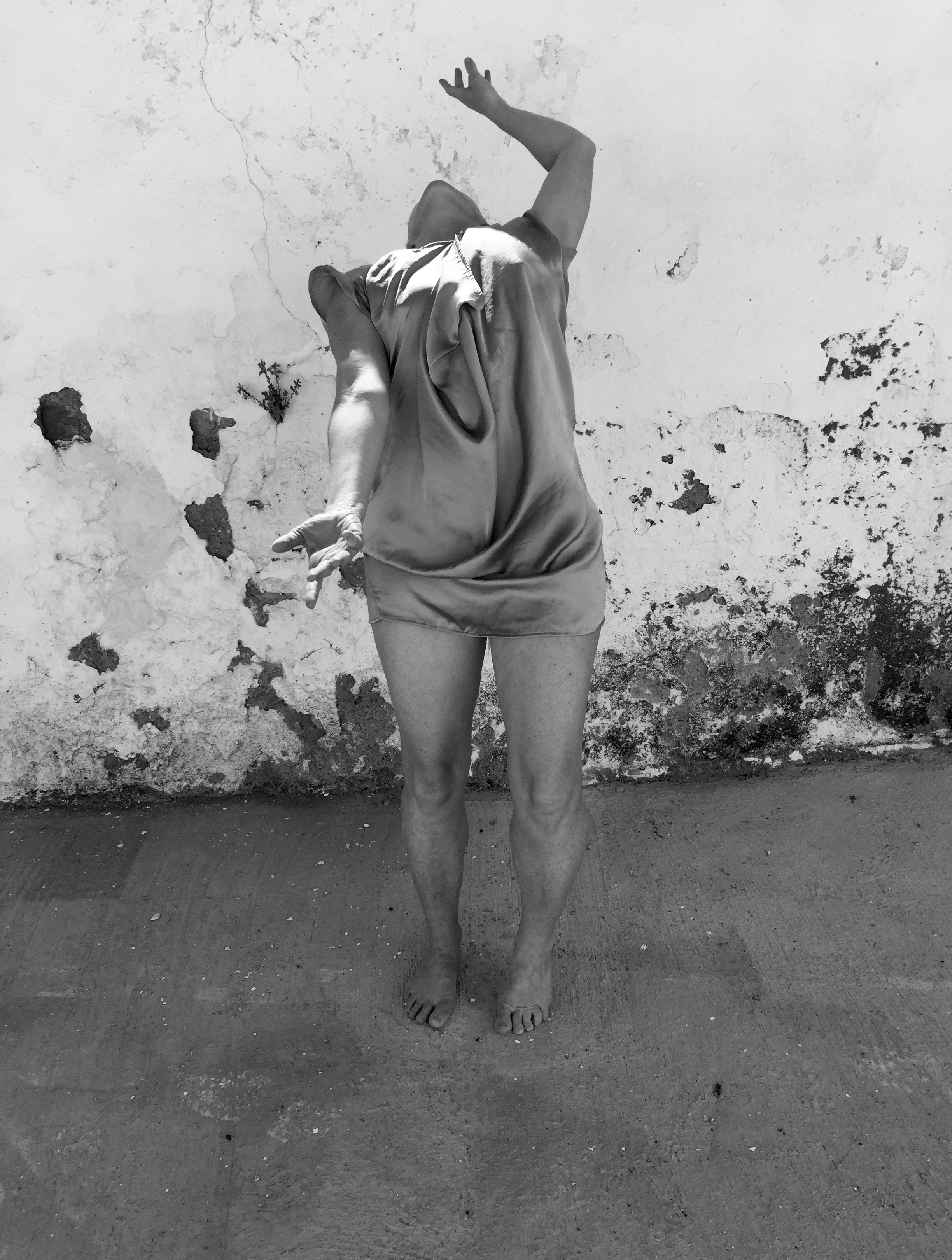

In Dancing Sculpture at the National Gallery of Victoria, Victorian College of the Arts dance students are recreating Gertrud Bodenweiser’s The Demon Machine, first created in Vienna in 1924. The work has a rich history and transformed modern dance; it uses female dancers to compose a dance in which lyrical pastoral gestures slowly shift into the rhythmic workings of a machine.

It arrived in London in 1929, the unusual abstraction and plasticity of the bodies attracted attention in the local press and signalled that, far from mere pleasure, “the art of dance brings to our notice facts of the greatest ethical value,” according to Ms Bodenweiser.

By 1936, the Austrian choreographer was very aware of the rising threat of Nazism in neighbouring Germany, and of its impact on many of her Jewish artistic friends.

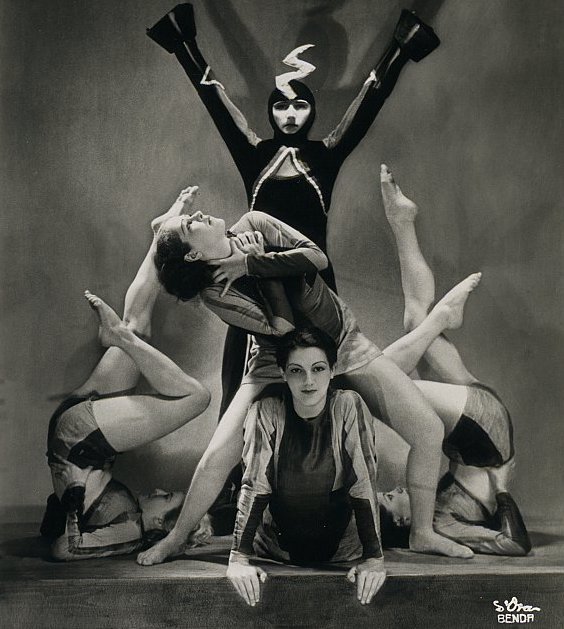

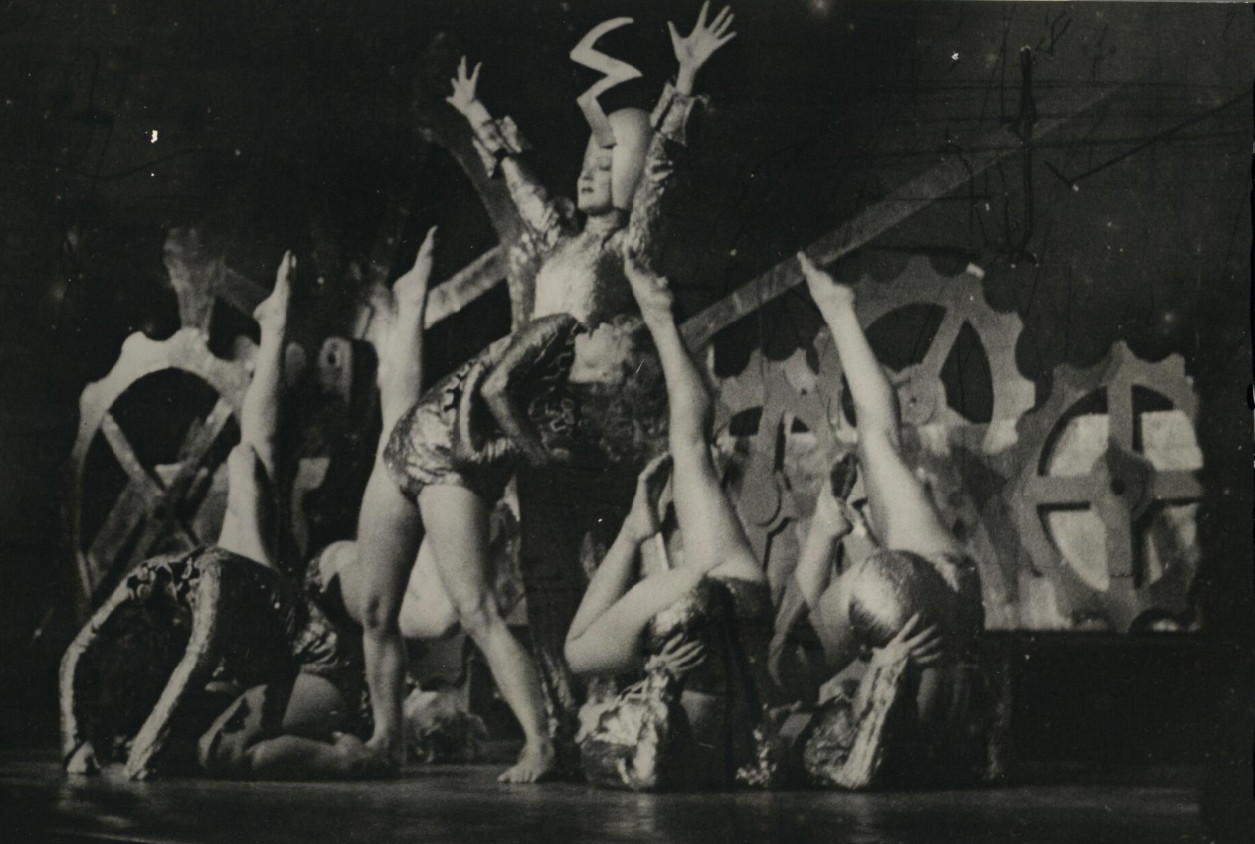

Accompanied by the strident music of Lisa Maria Mayer, Ms Bodenweiser recreated The Demon Machine to depict the resplendent Demon rising above the machinery of human bodies, with some dancers appearing shining and tranquil, and others perhaps kicking or turning in horror.

The strong diagonal lines, in both the electricity symbol on the Demon’s helmet and the extended limbs, suggest the clash of forces, inner and outer, that drive the machine.

With the annexation of Austria in 1938, Bodenweiser, herself Jewish, and her company of dancers set sail for South America, taking with them into exile many years of choreographic knowledge and artistic experimentation.

The famous Australian theatrical entrepreneur, J.C Williamson, hired a small troupe of Bodenweiser dancers to perform The Demon Machine in a revue touring outback Australia in 1939. The dancers performed crowd pleasers such as Viennese Waltzes, and other playful dances, but The Demon Machine remained a feature of the program intended to appeal to male audiences, perhaps because of the bare midriffs and the show of legs, but also because of its subject matter.

Well in advance of other dance repertoire of this period, the dancers were highly trained in modern dance techniques that gave them strong rhythmic propulsion while retaining an inner quality of expressive intensity.

By 1947 Bodenweiser had established herself with a dance company and school in Sydney and was creating new work for local audiences, including Cain and Abel (1940) and Abandoned to Rhythm (1942). The Demon Machine remained an important part of her repertoire.

On tour in New Zealand in 1948, a newspaper review observed that the music accompanying the dance added to the “maddening crescendo of mechanical movement as the machines assert their power over the human puppets… (and was) sombre when the dance was sombre, joyous at time of revelry”.

For The Demon Machine’s latest version, the Victorian College of the Arts dancers have been using this history to recreate the work, under the guidance of the Head of the VCA Dance program, Professor Jenny Kinder, herself also trained in the modern dance lineage, alongside the New Zealand choreographer, Carol Brown.

Ms Brown has researched the fascinating history of the Bodenweiser legacy and has also produced her own original solo performance called Acts of Becoming. Originally created in 1995 as an homage to the great Bodenweiser, the solo incorporates words and gestures from the archives of former Bodenwieser Tanzgruppe dancers.

In a recent Archibald prize painting, 102-year-old Eileen Kramer, a member of the original Bodenweiser company in Sydney, expressed an ‘inner stillness’ and her ongoing love of expressive dance. She is a living example of the inner spirit of modern dance in Australia with its extraordinary history and impact on future generations of artists.

Carol Brown, a student of the Bodenweiser dancer Shona Dunlop-McTavish, has recreated The Demon Machine for the Leap into the Modern symposium (12 August) curated by Professor Rachel Fensham (University of Melbourne) that accompanies the Brave New World: 1930s Australia exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. She is speaking at the symposium alongside other contemporary dance artists, such as Meryl Tankard and Shelley Lasica.

Banner image: The Demon Machine Benda D’Ora, 1936. Picture: National Library of Australia