Health & Medicine

The other side of happiness

How do you go about measuring the multifaceted and unique human quality that is creativity without killing it completely? New research aims to do just that

Published 21 June 2021

Can you give me three nouns that are completely unrelated to one another? What about four? Five? How about ten? And can you do it in a few minutes?

This is the Divergent Association Task (or DAT, in the acronym-loving world) which is used to measure a person’s creative thinking and potential.

The DAT was a key part of our first-of-its-kind, large-scale citizen science project which aimed to examine people’s feeling of insight or their ‘aha’ moment. And in August 2019, as part of National Science Week and in collaboration with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, we launched and ran The Aha Challenge.

The challenge posed a series of brainteasers involving words, symbols, images and logic, then asked for each person’s feelings about their response. It aimed to establish a fast and effective new way of measuring problem-solving ability and creative potential.

Around 15,000 people of all ages took part in the challenge, mostly Australians but also people from more than 100 other countries around the world, in all walks of life.

Health & Medicine

The other side of happiness

Our study, an international collaboration between researchers at the universities of Melbourne, Harvard and McGill was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). We found that simply asking people to name unrelated words can be a reliable measure of creativity.

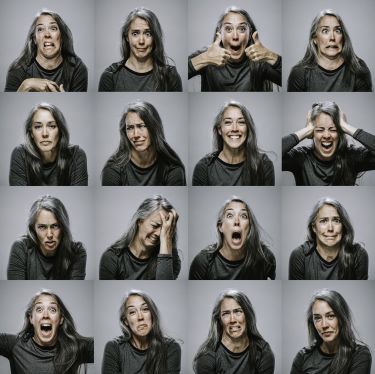

Psychologically, creativity has two main components — convergent thinking and divergent thinking — which work together when a person generates creative output. Convergent thinking means solving problems considering various constraints, and divergent thinking means generating novel and diverse solutions.

While studies of creativity and its nature are not new, relatively little is known about the process itself either in terms of its mechanisms or management.

There are many personal accounts of creativity from those experiencing and creating, but one thing that seems to stand out is how personal that process is to the creator.

Experimental studies of problem-solving and creativity have used a wide range of measures to try and quantify the underlying thought processes at work and find some commonality, but often these measures, by their very nature, suppress the freedom of thought likely to be conducive to creative output.

Health & Medicine

Anticipating our emotions

The Aha Challenge aimed to examine these measures broadly across a wide demographic to complement our existing very detailed, yet relatively narrow, experimental program.

The novel DAT measurement, which has the potential to measure divergent thinking and creative potential effectively and efficiently, was the focus of our research.

The DAT was originally devised by Dr Jay Olson, inspired by a childhood game involving thinking of unrelated ideas. He wondered whether a similar task could serve as a simple and elegant way to explore a person’s internal psychological space of word-meaning, their internal thesaurus, and find its boundaries.

The manipulation and use of this semantic (or word) space is an effective way to measure divergent thinking and, in turn, creative potential; this is the basis for several of the standard tasks used in creativity research.

The benefit of the DAT is that it’s easy to use, efficient and usually fun for people to do. It encourages freedom of thought rather than beating it out of people through hours of problem-solving.

Like a game of Go, the task is easy to do, but a real challenge.

Health & Medicine

How brain rhythms can reveal your personality

People are given four minutes to think of 10 nouns that are unrelated to one another and as far apart from each other in semantic space as possible.

The individual’s responses are then given a score based on the extent of the internal word-meaning space they map out.

Apart from the speed and the enjoyable ease of the task, another major advantage of the DAT is that the responses can be scored automatically using existing models of semantic distance based on millions of pages of published text.

In theory, this all sounds great, but in order to test the DAT, it needed to be placed in the context of more traditional measures of creativity and problem solving and tested across many more people.

And this is where The Aha Challenge came in. You can try it yourself online to see your creativity score.

The DAT was just one of the tasks used in our challenge, alongside more standard measures of creativity, like the Alternative Uses Task, insight problems and brain teasers.

This meant we were able to compare data from the DAT with more standard approaches to assess the commonality between the approaches to creativity measurement.

Health & Medicine

Can your personality be good, or bad, for your health?

The DAT fared very well, correlating strongly with the other tasks in the measures of divergent thinking and the strong implication of creative potential. It also took less time than would normally be required to get the same data using more traditional approaches.

This does not mean, however, that the DAT replaces those other methods of measuring creativity.

For such a multifaceted and unique human quality as creativity, it will always be necessary to use multiple approaches to understand what’s happening, and it’s more than likely we will never truly understand it without killing it completely.

However, the DAT does provide a very easy ‘in’ and has an important potential use in education, once a child becomes literate and is able to do the task.

Its brevity and ease of use come to the fore if we’re looking at education and, at least conceptually, it may be independent of the language in which the task is performed: as long as there are nouns, it should work.

Creativity is fundamental to human life. The more we understand its complex mechanisms, the more likely we will be able to encourage it in all its forms, even if it’s just to know when to let it go and be as unique and opaque as it sometimes seems to be.

Banner: Getty Images