The fight to save Syrian antiquities

Scholars across the globe have joined forces to preserve the beleaguered country’s cultural heritage for all our sakes

Published 13 January 2016

For Andrew Jamieson, the conflict unfolding in Syria is a catastrophe on multiple levels – professionally and personally.

By day (or more correctly, semester) Dr Jamieson is a senior lecturer and celebrated teacher of Classics and Archaeology in the University of Melbourne’s School of Historical and Philosophical Studies.

During sabbatical and non-teaching periods, he heads for archaeological sites – either within Australia or overseas to Egypt, Lebanon and Syria – to conduct fieldwork and research.

His partner is Syrian and together they own an apartment in Aleppo, the largest city in Syria and the world’s oldest, continuously inhabited metropolis.

“In Syria, I found a country of imposing intact ruins, extraordinarily evocative landscapes, and hospitable cultured peoples,” says Dr Jamieson.

“I’ve been fortunate to be involved in a number of archaeological excavation project. Over the years and in numerous conversations I’ve frequently heard Syrians describe Syria, both ancient and modern, as a ‘mosaic’.”

Many Syrians see their country as made up of discrete parts that fit neatly and harmoniously together.

Tragically, the war in Syria has shattered this mosaic. But in talking to his Syrian friends and colleagues, Dr Jamieson is buoyed by their optimism that the tessellation may one day be restored.

METHOD OVER MAYHEM

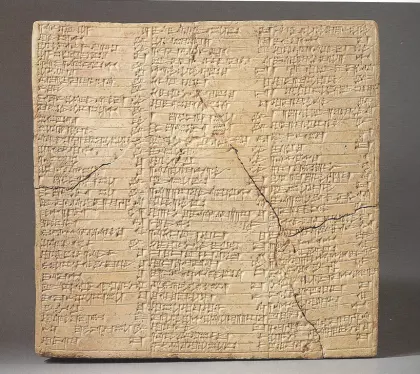

Since the commencement of hostilities in Syria, the world has lost a raft of precious and priceless artefacts from the country’s archeological sites and museums.

Illegal and clandestine excavation, systematic targeting by armed forces and mindless terrorist attacks have seen cultural treasures ending up on the black market, in private collections, or destroyed completely.

When Shirin International was created at the International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Basel in 2014, Andrew Jamieson was an obvious choice to represent Australia on its international committee.

He’d spent years travelling to Syria to conduct archaeological fieldwork and research, he’d lived in one of the country’s major cities on and off over these years.

A year later in 2015, following the first committee meeting of the Shirin International Committee in Bern, he was appointed to its Executive as Secretary.

Arts & Culture

Beauty, wine and death in the ancient world

“Shirin was created as an initiative of the global community of scholars in the fields of archaeology, art and history of the ancient Near East,” says Dr Jamieson. “And brings together many research groups that had worked in Syria prior to 2011.”

Shirin International’s stated purpose is to support governmental bodies and non-governmental organisations in preserving and safeguarding the heritage of Syria, including sites, monuments and museums.

Its membership includes specialist scholars and academics from across the globe.

“Our sights are set on a time, post-conflict, when the emphasis can shift from safeguarding and documenting the damage, towards restoration and reconstruction,” says Dr Jamieson.

HOW THE FIGHT’S BEING FOUGHT

What Shirin International’s fight to preserve, protect and salvage Syria’s unique and priceless antiquities lacks in war-like drama and clamour, it makes up for in determination and painstaking patience.

With indefatigable doggedness, Shirin’s members have been systematically collecting information on the damage and looting resulting from the current conflict and identifying those cases in which emergency actions or cooperation are needed.

Sciences & Technology

The palaeontology field keeps you on your toes

By collecting and collating the information gleaned from excavation directors who, in turn, rely on their local networks for information, Shirin is producing crucial damage assessments of individual sites and databases of Syrian museum inventories and historic environmental records.

Expert evaluations of the provenance of illicitly excavated or purchased artefacts and artwork are also provided by Shirin members.

“In its origins Shirin is the outcome of the concern of former excavation directors about their sites,” says Dr Jamieson.

“With their documentation and intelligence from local networks, these colleagues usually have premium information at their disposal which is crucial for analysing the present situation.”

It will be even more important for reconstruction once peace has returned to Syria.

Shirin members believe their organisation bears two features not fully shared by other NGOs operating in the region.

“We know of no other NGO that has considered the desperate situation of the museums in Syria in its program,” says Dr Jamieson.

Sciences & Technology

Laos jars are slowly revealing their secrets

FROM MELBOURNE TO SYRIA: A HISTORY OF ARCHEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION

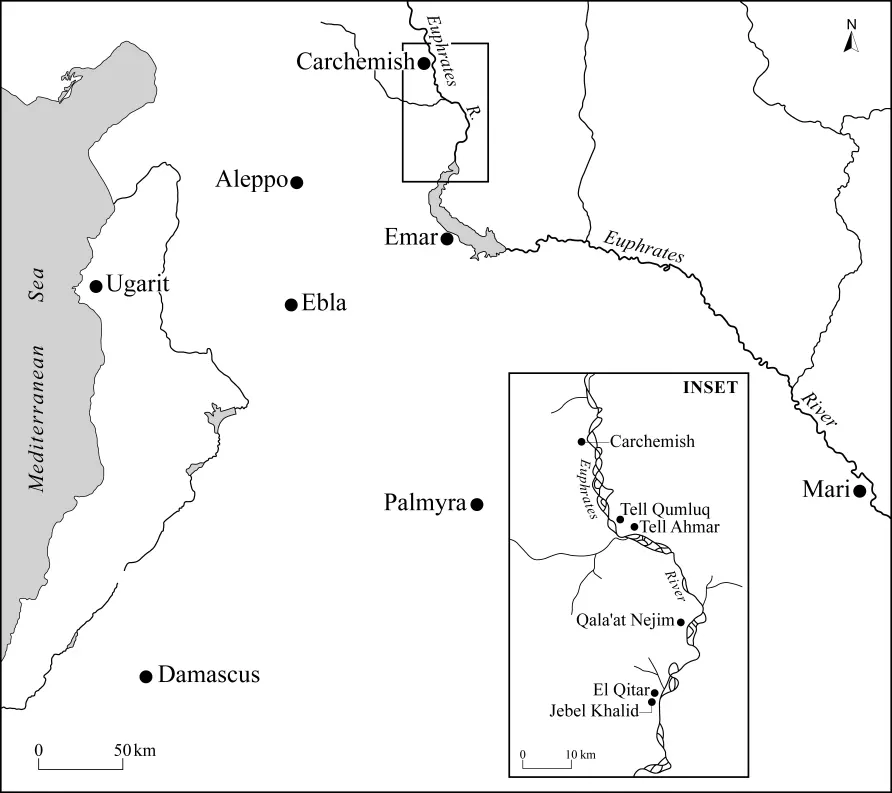

For almost four decades archaeologists from the University of Melbourne have been conducting archaeological fieldwork and research in Syria, particularly in the vicinity of the middle and upper Euphrates River valley.

“The University’s association with the area began in the early 1980s with the El Qitar project and the discovery of a Bronze Age fortress,” says Dr Jamieson.

“This work was followed in the late 1980s and 1990s with an expedition to Tell Ahmar, ancient Til Barsib, where evidence of a provincial centre of the Neo-Assyrian Empire was uncovered.”

Since 1986, a joint mission from the University of Melbourne and the Australian National University has regularly undertaken fieldwork revealing a major settlement of the Hellenistic period at the site of Jebel Khalid.

Before the conflict the University of Melbourne embarked upon a new program of research in Syria. This work formed part of a joint research collaboration project known as the Syrian-Australian Archaeological Research Collaboration Project which commenced in 2008.

Owing to the instability in Syria the project is currently on hold.