Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Passengers onboard the First Fleet received a harsh introduction to their new home’s climate before they even landed. Their diaries and letters reveal just how hard it was

Published 2 April 2018

The women screamed as the huge waves crashed loudly on the wooden deck. Horrified, they watched the foaming torrent wash away their blankets. Many dropped to their knees, praying for the violent rocking to stop. The sea raged around them as the wind whipped up into a frenzy, damaging all but one of the heavily loaded ships.

The severe storm was yet another taste of the ferocious weather that slammed the First Fleet as it made its way across the Southern Ocean in December 1787. Now, after an eight-month journey from England in a ship riddled with death and disease, the passengers’ introduction to Australia was also far from idyllic.

The unforgiving weather that greeted the First Fleet was a sign of things to come. More than once, intense storms would threaten the arrival of the ships and bring the new colony close to collapse.

So how did the early arrivals to Australia deal with such extreme weather? Have we always had a volatile climate? To answer these questions, we need to follow Australia’s colonial settlers back beyond their graves and trace through centuries-old documents to uncover what the climate was like from the very beginning of European settlement.

Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

By poking around in the settlers’ old diaries, letters and newspaper clippings, we can begin to piece together an idea of what the country’s climate was like long before official weather measurements began.

When the British sailed into Australian waters, they had no idea of what awaited them. Perhaps they expected that life would resemble their other colonial outposts like India, or an undeveloped version of England. With enough hard work, surely the land could be tamed to support their needs.

But when the First Fleet sailed into Sydney Cove, they unknowingly entered an ancient landscape with an unforgiving climate.

Even before Governor Arthur Phillip set foot in Botany Bay, violent storms had battered the overcrowded ships of the First Fleet. During the final eight-week leg of the journey from Cape Town to Botany Bay, the ships had sailed into the westerly winds and tremendous swells of the Southern Ocean. Ferocious weather hit the First Fleet as it made its way through the roaring forties in November–December 1787.

Although the strong westerlies were ideal for sailing, conditions on the ships were miserable. Lieutenant Philip Gidley King described the difficult circumstances on board HMS Supply: ‘Very strong gales … with a very heavy sea running which keeps this vessel almost constantly under water and renders the situation of everyone on board her, truly uncomfortable’. Unable to surface on deck in the rough seas, the convicts remained cold and wet in the cramped holds.

Captain John Hunter described how the rough seas made life on the Sirius very difficult for the animals on board:

The rolling and labouring of our ship exceedingly distressed the cattle, which were now in a very weak state, and the great quantities of water which we shipped during the gale, very much aggravated their distress. The poor animals were frequently thrown with much violence off their legs and exceedingly bruised by their falls.

Arts & Culture

How a quest for the past found a living present

It wasn’t until the first week of January 1788 that the majority of the First Fleet sailed past the south-eastern corner of Van Diemen’s Land, modern-day Tasmania. As his boat navigated the coast, surgeon John White noted: ‘We were surprised to see, at this season of the year, some small patches of snow’.

According to Bowes Smyth, faced with a ‘greater swell than at any other period during the voyage’, many of the ships were damaged, as were seedlings needed to supply the new colony with food. Bowes Smyth continued:

The sky blackened, the wind arose and in half an hour more it blew a perfect hurricane, accompanied with thunder, lightening and rain … I never before saw a sea in such a rage, it was all over as white as snow … every other ship in the fleet except the Sirius sustained some damage … during the storm the convict women in our ship were so terrified that most of them were down on their knees at prayers.

Finally, on 19 January, the last ships of the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay. But after just three days there, Phillip realised that the site was unfit for settlement. It had poor soil, insufficient freshwater supplies, and was exposed to strong southerly and easterly winds.

With all the cargo and 1400 starving convicts still anchored in Botany Bay, Phillip and a small party, including Hunter, quickly set off in three boats to find an alternative place to settle. Twelve kilometres to the north they found Port Jackson.

On 23 January 1788, Phillip and his party returned to Botany Bay and gave orders for the entire fleet to immediately set sail for Port Jackson. But the next morning, strong headwinds blew, preventing the ships from leaving the harbour. A huge sea rolling into the bay caused ripped sails and a lost boom as the ships drifted dangerously close to the rocky coastline. According to Lieutenant Ralph Clark:

Arts & Culture

The Irish Rising that shaped Australia

If it had not been by the greatest good luck, we should have been both on the shore [and] on the rocks, and the ships must have been all lost, and the greater part, if not the whole on board drowned, for we should have gone to pieces in less than half of an hour.

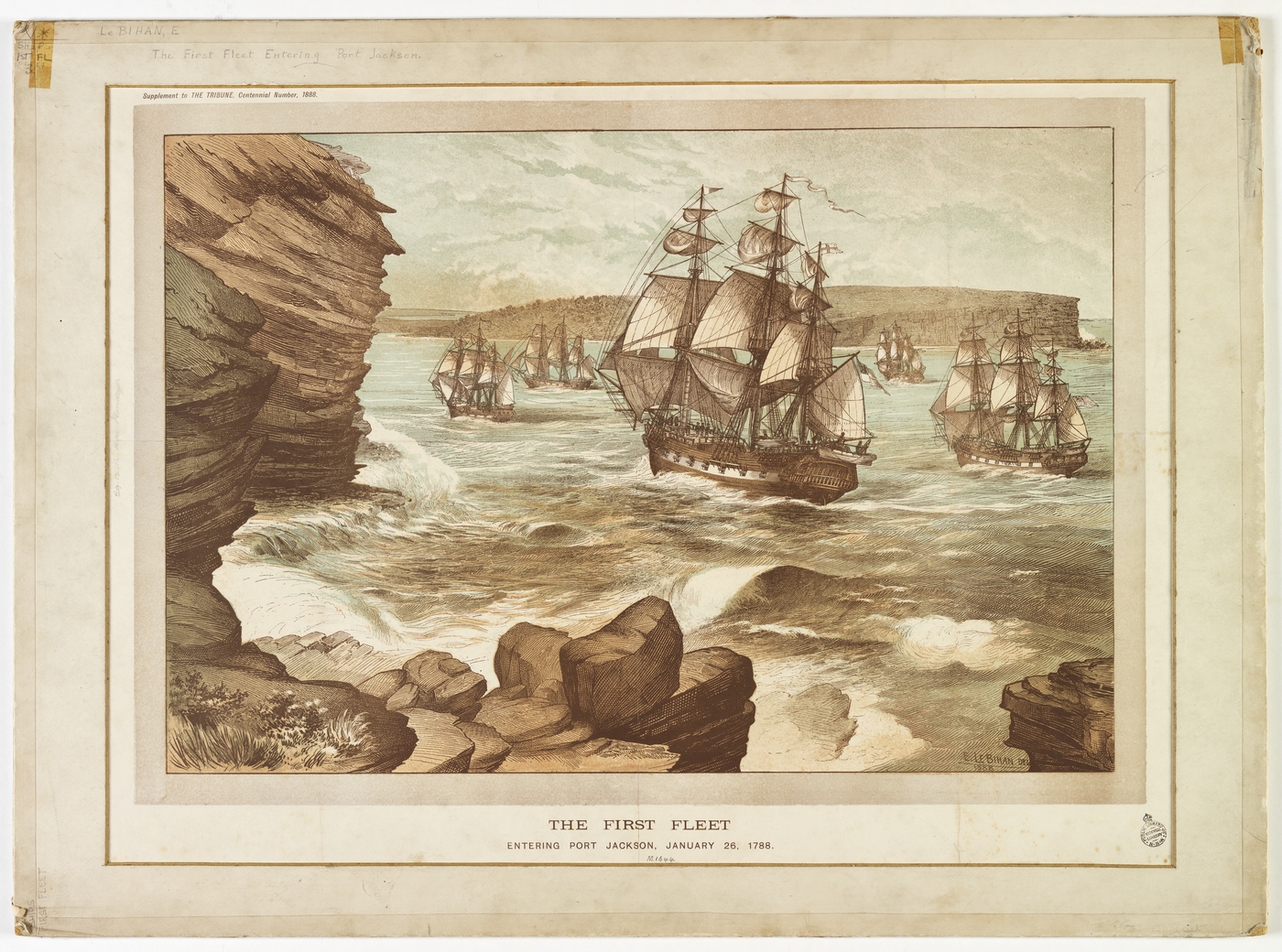

By 3 p.m. on 26 January 1788, all eleven ships of the First Fleet had safely arrived in Port Jackson. Meanwhile, while waiting for the others to arrive, Phillip and a small party from the Supply had rowed ashore and planted a Union Jack, marking the beginning of European settlement in Australia.

After such an epic journey, the whole ordeal was washed away with swigs of rum. Unknowingly, it marked the start of our rocky relationship with one of the most volatile climates on Earth.

This is an edited extract from Joelle Gergis’s Sunburnt Country: The History and Future of Climate Change in Australia, out 2 April from Melbourne University Press. RRP $34.99, Ebook $16.99, from mup.com.au and all good bookstores.

This article has been co-published with The Conversation.

Banner image: The H.M. Bark Endeavour, part of Captain Cook’s first voyage of discovery to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771, Oswald Brett