Politics & Society

Data security in the spotlight

We’re being asked to provide more and more information about ourselves online, including in the recent New Zealand census – but should we trust assurances that our privacy is closely guarded?

Published 25 April 2018

As more government services are moved online, the powers that be have been quick to reassure us that this transition poses no threat to our privacy or personal security. But too often there is a lack of transparency about the associated risks, and a lack of information that allows the public to make informed decisions about their data.

Recently, more than 3 million New Zealanders filled out the country’s census, but as Stats NZ, New Zealand’s official data agency, states: “This census is different. We are aiming to collect most of the census information online.”

The New Zealand census happens every five years and is “the official count of how many people and dwellings there are in New Zealand”. The information is gathered by asking everyone to complete a set of questions about themselves and their household. Again, the New Zealand government provided assurances that “we’ve checked and tested that the systems and processes we have designed are robust, so that we can meet our commitment to look after and store your information securely”.

But, how trustworthy are these reassurances that this information is being closely guarded?

We recently analysed the deployment of the census, and found the answer, in short, isn’t a good one.

Politics & Society

Data security in the spotlight

Stats NZ make a number of statements on their website about the security of their online census. The privacy and confidentiality page states:

Does anyone see my information during transmission? No, census forms are transmitted to Stats NZ using encryption to prevent unauthorised access. Only Stats NZ can decrypt it

Data cannot be compromised when Transport Layer Security (TLS) is in use

You can verify that you are communicating with Stats NZ by selecting the key or the lock

All census forms submitted to Stats NZ won’t be read by anyone other than authorised staff at Stats NZ

All of which sounds great, but isn’t true.

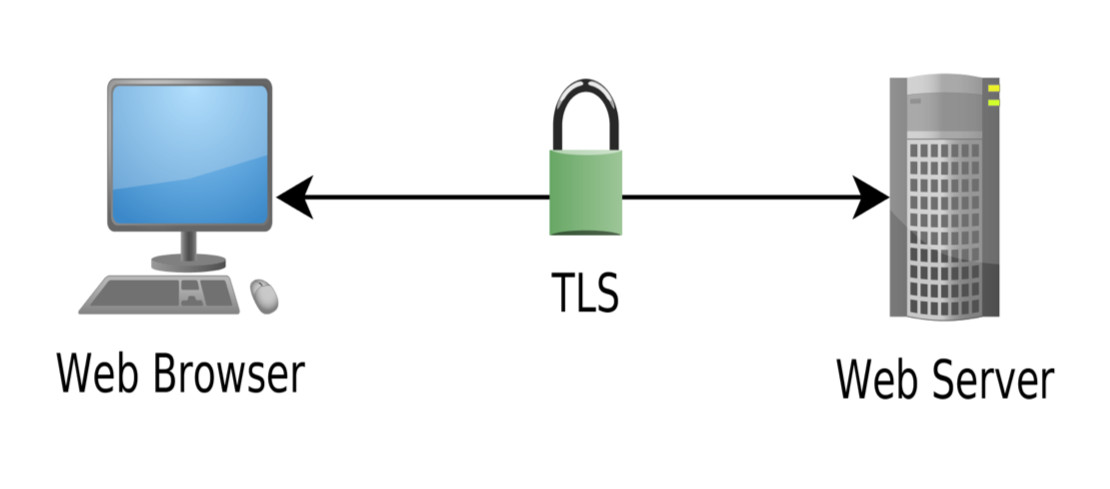

TLS is at the heart of security on the internet and, in turn, at the centre of security for New Zealand’s online census. Whenever you see the green padlock, or secure indicator in your web browser, that’s TLS at work.

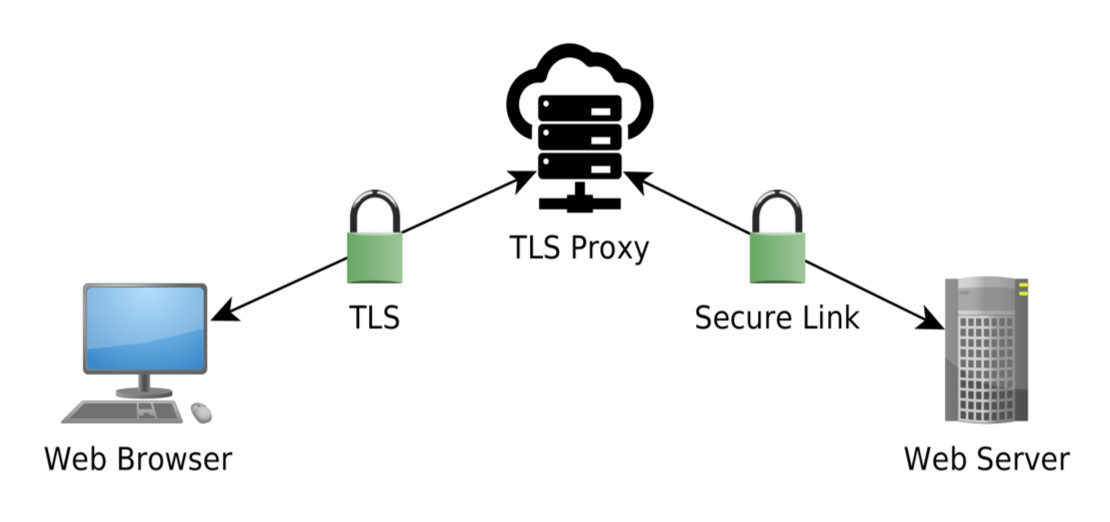

Proxies are becoming quite common, particularly in e-commerce. They are employed as a defence against cyber attacks – shielding the real server from attack. The TLS Proxy is typically run by an organisation with a global high-performance network, which gives it the capacity to handle even the largest Denial of Service attacks.

In essence TLS provides an end-to-end private connection between your web browser and the server. It uses encryption to protect everything you send and receive, as well as providing assurance you are communicating with the correct server.

On the face of it, TLS seems to provide everything Stats NZ claims it does. And it would, if it was being used in the manner for which it was designed.

Sciences & Technology

The simple process of re-identifying patients in public health records

However, there is an important detail that Stats NZ don’t mention. They aren’t using plain TLS, but something called a TLS Proxy instead.

A TLS Proxy is an additional server that acts as a sort of gatekeeper for the connection. Instead of a web browser connecting directly to the Stats NZ server, it connects to the TLS Proxy that’s run by a commercial company, in this case, a company called Incapsula.

The Incapsula server inspects the web requests sent to Stats NZ and filters out any malicious content, before forwarding the legitimate traffic to the real server.

There are two core issues at play here: privacy and a lack of transparency.

The TLS Proxy sees everything that is sent to Stats NZ, and so it has to be fully trusted to keep the data it sees both secure and private.

There are some systems that use an additional layer of encryption at the client end, so that the user’s data is encrypted in a way that even the proxy cannot read. But there’s no indication that this system was used in the NZ census. Even if it was used, the proxy is still trusted to serve the right encryption code to allow for proper encryption.

When we analysed Western Australia’s deployment of the iVote Internet voting system, a clear focus was the trust implications of TLS Proxies. We aren’t suggesting that Incapsula cannot be trusted. The issue is not about them. The concern is the fact that such a trust requirement exists, and isn’t mentioned.

But it’s the inaccurate information provided by Stats NZ about the security and privacy of the online census that is the greatest concern.

It gives the false impression that data cannot be read while it’s being transmitted to Stats NZ – that is, the data cannot be decrypted by anyone other than Stats NZ – and that the user can be certain they are communicating with Stats NZ.

Sciences & Technology

Data privacy and power

In fact, the data can be read by Incapsula, and the certificate only proves that the user is communicating with Incapsula, not Stats NZ itself.

This raises a second security concern. The secret encryption key, or private key, which is used to decrypt the data and authenticate the server, is supposed to be carefully protected and should only reside on the server it relates to.

But when using a TLS Proxy, the private key is distributed across servers in the global network of the provider, and any of those servers can appear as Stats NZ.

Our non-exhaustive search found that servers in Australia, the US, and Europe, as well as New Zealand, all had the Stats NZ private key.

This raises the possibility of impersonation, and highlights a clear security flaw of the key when it’s held on foreign servers, outside of the jurisdiction of New Zealand.

With this same key used throughout the network, it could allow for the interception of any encrypted traffic intended for Stats NZ.

Many of those countries are considering laws that mandate decryption of data carried by service providers within their borders.

We’ve shared all this information with Stats NZ. The key issue here isn’t the use of a TLS Proxy, but the lack of transparency over its use, and crucially, the incorrect statements on the Stats NZ website that give the impression that no TLS Proxy is in use.

It isn’t the role of government agencies to make trust and privacy decisions on behalf of the end-user – that has to be up to the person entering their information.

But any organisation like Stats NZ has a responsibility to provide accurate and sufficient information about their security so the public can make an informed decision about how they want to interact with government online.

Banner image: Sarah Fisher/University of Melbourne