Environment

Getting regional development right

An oral history project is preserving the memories of the people who fished the Gippsland Lakes before commercial fishing was shutdown

Published 2 April 2021

With little fanfare or attention, commercial fishing in the Gippsland Lakes in eastern Victoria ceased on 1 April 2020.

The small-scale commercial fishery, which was crucial to the establishment of the town of Lakes Entrance roughly 150 years ago, was closed by the Victorian State Government as part of its Target One Million plan to grow recreational fishing. But this 2018 election promise also spelled the end of an era for many family fishing businesses.

The Gunaikurnai people were the first to fish the Gippsland Lakes using spears, nets and canoes. In the 1840s, it was estimated that 3,000 Gurnaikurnai people were living in the Gippsland lowland coastal area.

By the early 1860s, the Chinese fish-curing trade began. These innovative producers would keep the fish alive until they could be processed, helping to stabilise the supply of seafood products.

In the 1870s, Chinese fishermen set up drying racks in what is now the town of Metung.

Environment

Getting regional development right

Europeans followed – coming to fish the Lakes, living along the shores in tents crafted from ti-tree boughs and thatched with reeds.

With the opening of the railway line in 1878, a safe and reliable transport link between Gippsland and Melbourne was established, but the steamers were still vital, transporting fish in huge ice chests to the nearest rail connection.

By late 1892, there were around 100 fishing boats operated by 200 professional fishermen of European and Chinese descent, along with their families, who were an integral part of the industry.

BUILDING AN INDUSTRY

Descendants of these early fishing communities continued to raise their families on the Lakes, supplying the local and Melbourne markets with fresh seafood, up until April 2020.

Gippsland Lakes fishermen used mesh nets and seine nets, stake nets and pots to catch fish, including black bream, prawns, crabs, flathead, tailor, silver trevally, mullet and garfish.

Many of the fishing techniques used by modern fishers used the most environmentally benign forms of fishing with minimal emissions. Mesh nets were set on the bottom of the lake overnight, waiting to catch fish as they swam past.

Seine nets are shot in an arc anchored to the shore, with both ends of the net gradually pulled together and fish funnelled into a bag in the middle of the net. Selected species are scooped out while others are released back into the Lakes.

Sciences & Technology

How data can keep fish and chips on the menu

Stake nets were used to catch prawns set by anchors in the tide.

The daily catch was delivered to the co-op and prepared for transport either to local suppliers or to Melbourne and Sydney for distribution to restaurants and fishmongers.

Ten licence holders, many of them ‘generational’ fishermen whose families had commercially fished the lakes for decades, pulled in their nets for the last time on the evening of March 31, 2020 at the end of a beautiful, sunny and ultimately, sad, day for them and their families.

Thanks to a team of fishers, historians, photographers, and anthropologists, the fishers’ stories and local environmental knowledge won’t be forgotten, despite the closure, through an exhibition bringing their stories to life.

End of an Era: the Last Gippsland Lakes Fishermen presents the social and cultural history of the Gippsland Lakes fishery through the images and words of the last ten licence-holding Gippsland Lakes fishing families.

But it also provides a ‘how to’ template so other communities can run their own oral history projects to record their experiences, curate material and present them online, for themselves and a broader audience.

In 2017, I interviewed Mary Mitchelson who fished commercially with her husband and brother in law, Frank Mitchelson in the 1960s and 70s.

Using oral history life story methods, supported by the National Library of Australia (NLA) Oral History and Folklore unit and the, now defunct, eScholarship Research Centre (ESRC) at the University of Melbourne, I began to document the stories of the families who worked there, in their own words.

Lynda Mitchelson-Twigg, whose husband and father were both affected by the compulsory licence buy-back, has been our key community contact, working to pull the exhibition together, while holding down her full-time job and raising a family.

The stories of the Gippsland Lake fishers highlight the connection these families have to the land and sea, the artisanal methods used, the strength of relationships built around the water and their contribution to coastal communities and the Australian fishing industry as a whole.

But it’s also about the deep knowledge possessed by local fishermen – knowledge that goes back through generations to the start of the commercial fishery.

Matt Jenkins, whose father Rob fished the lakes before him, says this kind of environmental knowledge pre-dates them.

“Every day is different and something out of the ordinary pops up from time to time. We get visits from mud crabs and sea turtles, doing things they’ve been doing for thousands of years. We’ve only been doing this for five minutes and we’ve only just started to notice them.”

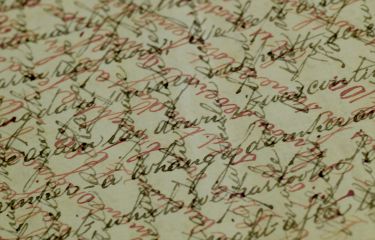

Arts & Culture

Criss-cross history hidden in a letter

He learned which nooks and crannies provided shelter no matter what the wind direction, and how to use the quiet, traditional fishing methods that involve holding nets by hand.

Stories like this give us an insight into an industry that was central to many small coastal communities, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

They are stories of changing communities and cultures, and they remind us of how everyone’s lives are valuable and connected – whether they’re about the young woman who cleaned the fish before throwing it onto the cart, or the old man who brought the ice in before there was a fridge.

Telling local stories adds a rich texture to our national story and identity, but they can also document our changing environment. We have much to learn about water and fisheries management by listening to the people who have worked in those environments, sustainably, for years.

There are also those unexpected stories from the Gippsland Lakes – how a day on the lakes still offered up surprises to those who fished them, as the currents brought in unexpected visitors from northern climes.

There are places like ‘The Fighting Shot’ – locations that were so highly prized that the fishermen would argue about who got there first to ‘thrown the shot’.

And there’s the endless stream of free advice including, “You’ve got to think like a fish. If you don’t, you’ll lose him.”

Oral histories like this are important because they give voice to the experience of ordinary people, telling local stories that provide texture and nuance to national narratives.

Stories of ordinary life remind us of how everyone’s lives are valuable and give us a window into the diversity found in our own backyard.

The project team for end of an era are: Ms Lynda Mitchelson-Twigg (Lake Entrance Community) Dr Nikki Henningham (University of Melbourne) Leigh Henningham (Photographer) Dr Tanya King (Deakin University) Donna Squire (Photographer) Geoff Stanton (Photographer)

Funding and/or in-kind support was provided by: Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) The National Library of Australia The University of Melbourne Deakin University

The following fishermen and their families: Arthur Allen James Casement Michah Davy Ross Gilsenan Mathew Jenkins Rob Jenkins Gary Leonard Harold Leonard Frank Mitchelson Harry Mitchelson Mary Mitchelson Kevin Newman Leigh Robinson Peter Tabone Andrew Twigg

End of Era runs until 8 April at the Slipway in Lakes Entrance. The exhibition then opens in Geelong at the Deakin Waterfront on May 6 and runs for three weeks.

Banner: Leigh Henningham