Arts & Culture

Getting your Monet’s worth in a changing art market

The much-anticipated new art museum is opening in the United Arab Emirates later this year; here’s why it should be considered a global art envoy rather than an agent of the West

Published 15 August 2017

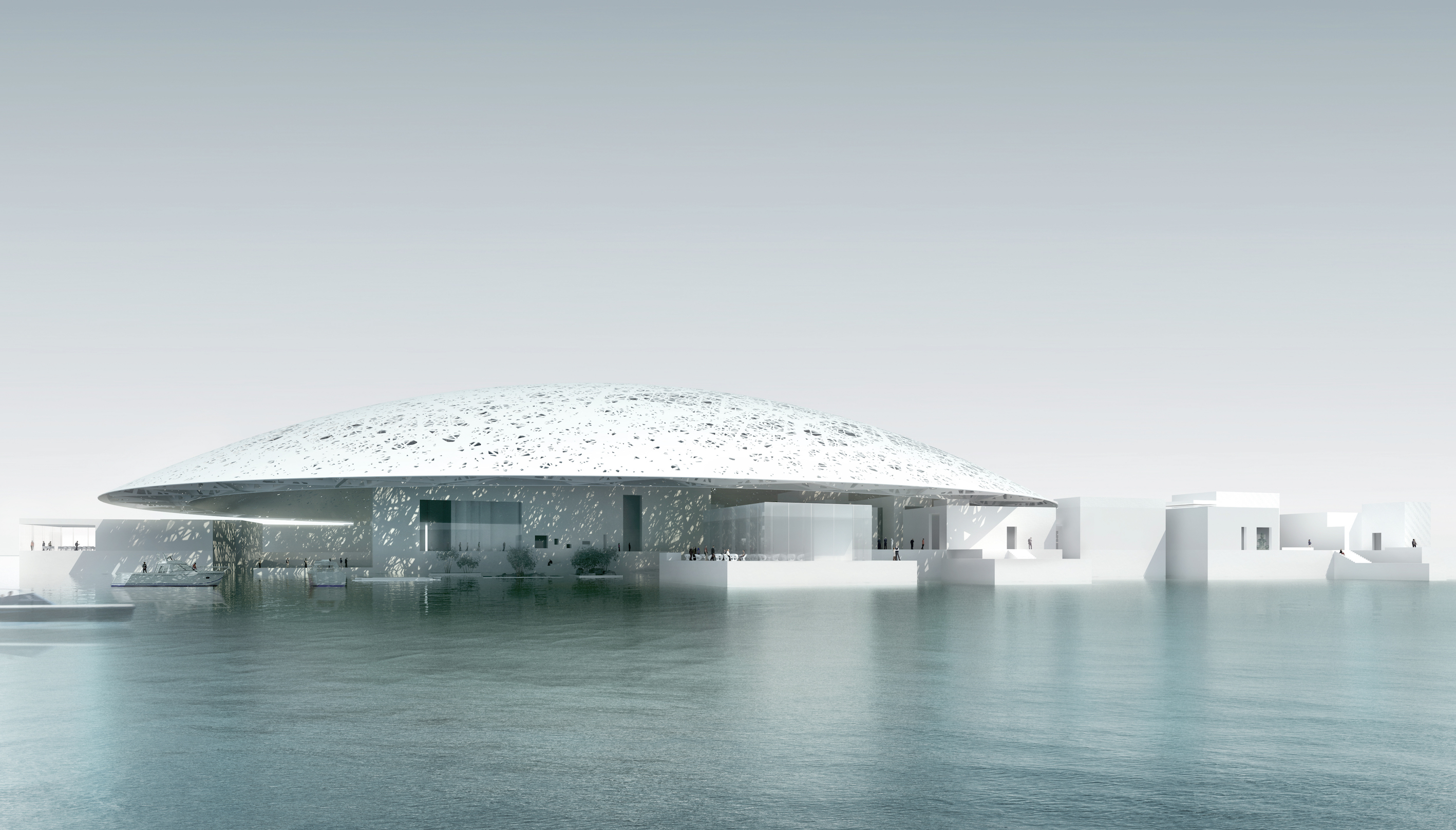

The Louvre Abu Dhabi is scheduled to open its doors to the public in November 2017 following ten long years of planning. It marks the latest international cultural franchising deal, where big name museums and galleries lend their brand to overseas institutions.

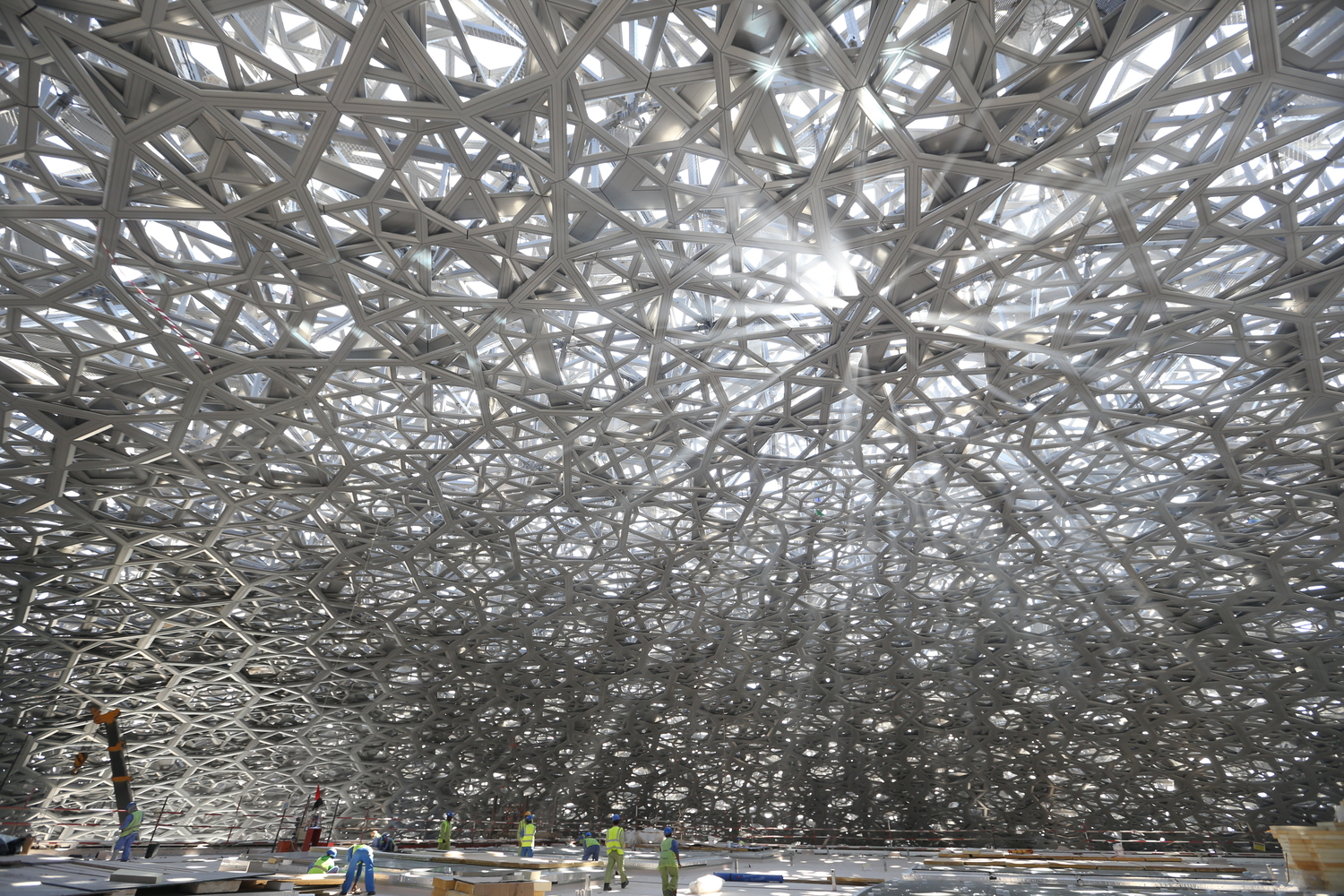

This ambitious and controversial project has attracted criticism aimed at everything from employing a migrant construction labour force under harsh conditions, to undermining the dignity of French culture (similar to the Guggenheim franchises being labelled ‘McGuggenheims’).

But perhaps the biggest criticism, led by Professor Andrew McClellan (Tufts University, author of The Art Museum from Boullée to Bilbao) is one of cultural imperialism; that the new museum will impose Western notions of art, culture and history in the Gulf Region.

However, careful consideration of the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s catalogue tells a different story; one of commitment to a meaningful dialogue between Eastern and Western cultural outlooks.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi forms the centre-piece of a 27 square kilometre man-made island off the coast of Abu Dhabi that has been conceived as a commercial, tourist, and cultural hub for the entire Gulf region; part of the United Arab Emirate’s economic strategy for when the oil runs dry.

Arts & Culture

Getting your Monet’s worth in a changing art market

When complete, Saadiyat Island will comprise a network of iconic cultural developments. Besides the Louvre Abu Dhabi there will be a new Guggenheim Museum by Frank Gehry, a museum dedicated to the founding president of the UAE formulated by Norman Foster, a maritime museum by Japanese architect, Tadao Ando, and a performing arts centre designed by the celebrated late Iraqi-British architect, Zaha Hadid.

The island will also contain a series of luxury hotels together with a golf-course, a beach club and shopping malls lined with international luxury outlets.

As the opening flagship attraction for the development, there is clearly much at stake in achieving a smooth launch for the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Writing in The Journal of Curatorial Studies, Professor McClellan questions the curatorial rational of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, arguing that it “appears set to re-inscribe the familiar western story of art” into the Gulf Region and that this will result in the Louvre “essentially reproducing itself in the Persian Gulf while claiming to do something new and different.”

But the new art museum is not simply another Louvre; it is a new institution in itself, which is ‘borrowing’ the Louvre brand for 20 years (to the tune of 1.3 billion USD, or 1.6 billion AUD).

The so-called ‘universal survey’ approach adopted by the Louvre and other museums in the past has undoubtedly resulted in a markedly pro-Western bias within many museum collections. Though founded on the ideal of a supposedly ‘universal survey’ of culture, in practice this has always meant that the vast encyclopaedic museums of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have reinforced a peculiarly Western notion of cultural distinction from Ancient Greece through to the European Renaissance and so on.

This concern may well have been valid during the project’s early years, when much about it was still to be defined. It has become harder to sustain, however, following the publication of Louvre Abu Dhabi: Birth of a Museum, a lavishly illustrated catalogue accompanying an exhibition of the same title held in 2014.

This catalogue outlines the recent acquisitions made for the museum’s permanent collection that are funded from its staggeringly impressive annual accessions budget of USD 56 million (70 million AUD).

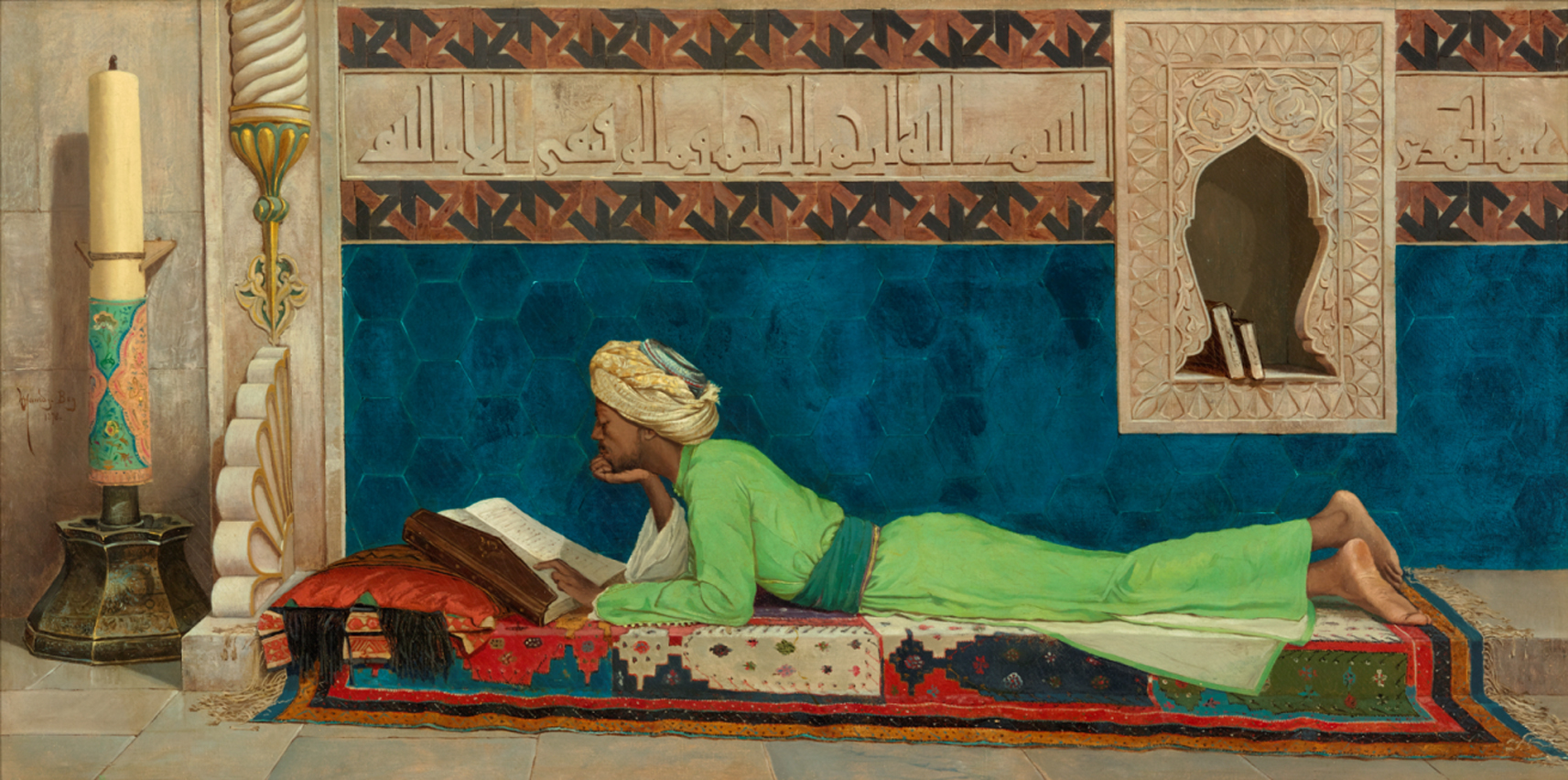

Far from following a policy of obvious ‘name brand’ acquisitions, the catalogue demonstrates the extent to which the curators have searched far and wide to locate strikingly distinctive and unusual objects that can be used to offer up fresh and intriguing cross-cultural comparisons between artefacts sharing certain affinities and similarities across time and space.

The earthy materiality of an ancient Bactrian sculpture of a female figure is juxtaposed with the neo-primitivist vigour of Yves Klein’s 1960 Anthropometry, a white canvas imprinted with the blue outlines of the bodies of two models who were contracted by the artist to cover themselves in paint before rolling onto the canvas as a form of ‘living paintbrush’.

The curators have also selected a series of striking, standalone works that powerfully evoke ideas of cross-cultural hybridity within themselves including, for example, an eighteenth century portrait of a European ambassador to the court of Constantinople by the Swiss Rococo artist Jean Étienne Liotard. The painting presents the ambassador clad in extravagant European attire while standing in a meticulously detailed Arab interior. It also demonstrates the artist’s simultaneous interest in introducing into the composition the flattened and surface-oriented emphasis of Islamic art more generally.

So too, a sixteenth century mother of pearl ewer from Gujarat in Western India has been selected for its intriguing afterlife in Baroque Naples. Here the ewer was taken and adapted for a new purpose via the addition of elaborate Neapolitan gold-smith work so that it now appears to hover somewhere between an Indian princely possession and an object of finely worked exotica to be displayed in an Italian Baroque cabinet of curiosity.

Confirmation of the success or otherwise of this novel approach, of course, will not be evident until the new museum opens its doors to the public later this year.

Still, the catalogue offers up the tantalising possibility that the Louvre Abu Dhabi may well be poised on the brink of presenting a new model for the universal survey museum for the twenty-first century.

This new curatorial agenda of cross-cultural exchange and comparison has the potential, in turn, to break down the old polarities existing between Eastern and Western understandings and to replace them with a new more inclusive form of art historical survey museum that is, at last, truly global in scope.

Banner image: Louvre Abu Dhabi