Arts & Culture

Being open to emotion in art

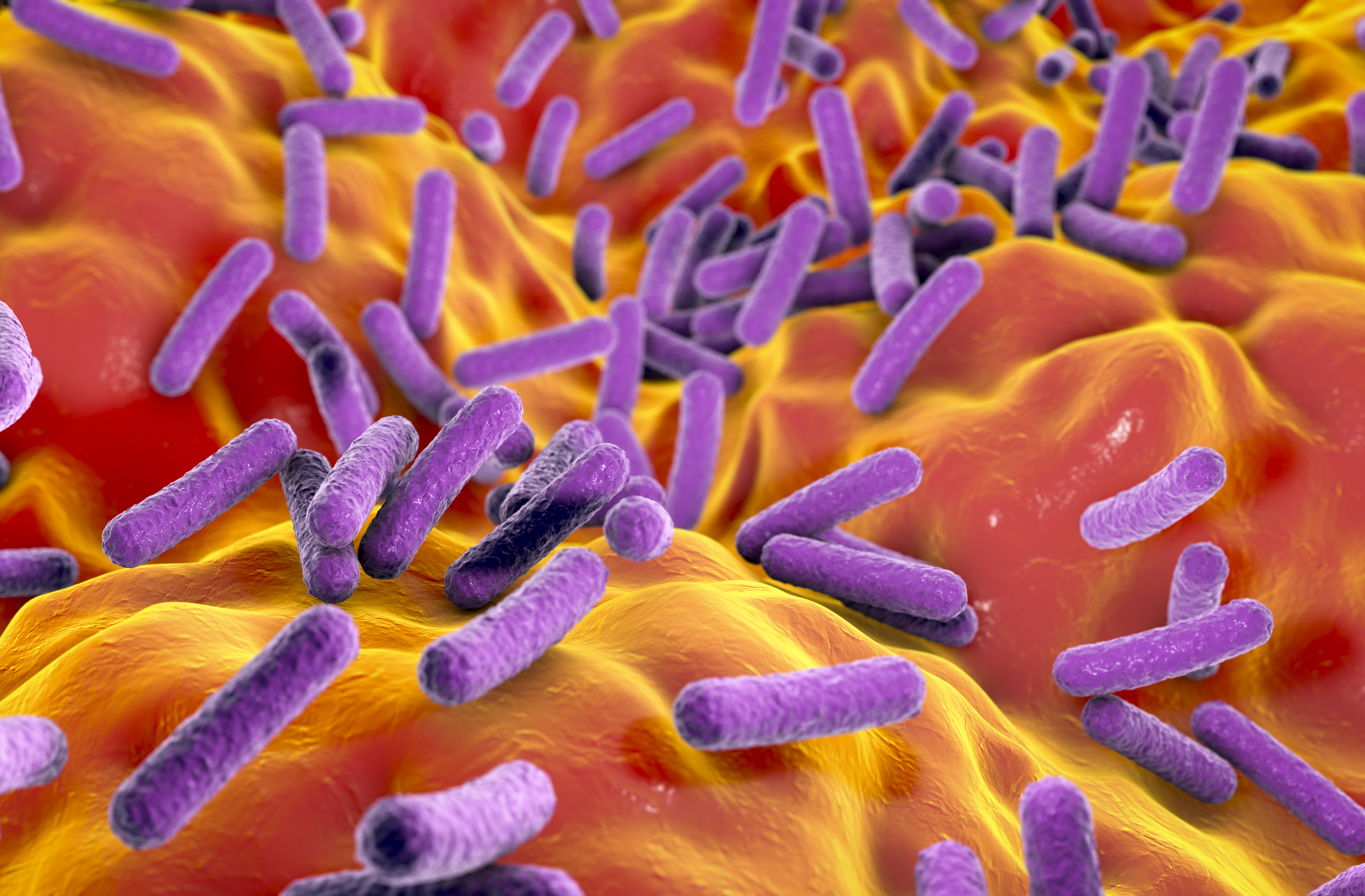

Research is revealing the connection between our microbes and our mental health, suggesting that your ‘gut-feeling’ is not just metaphorical

Published 19 July 2021

When we think about the biology of mental health, our mind usually goes straight to the brain. After all, this is the organ responsible for our cognition, memory and control over our bodies.

But as studies reveal the interactions between our biological systems and colonising microbes, research has also uncovered links to our mental health.

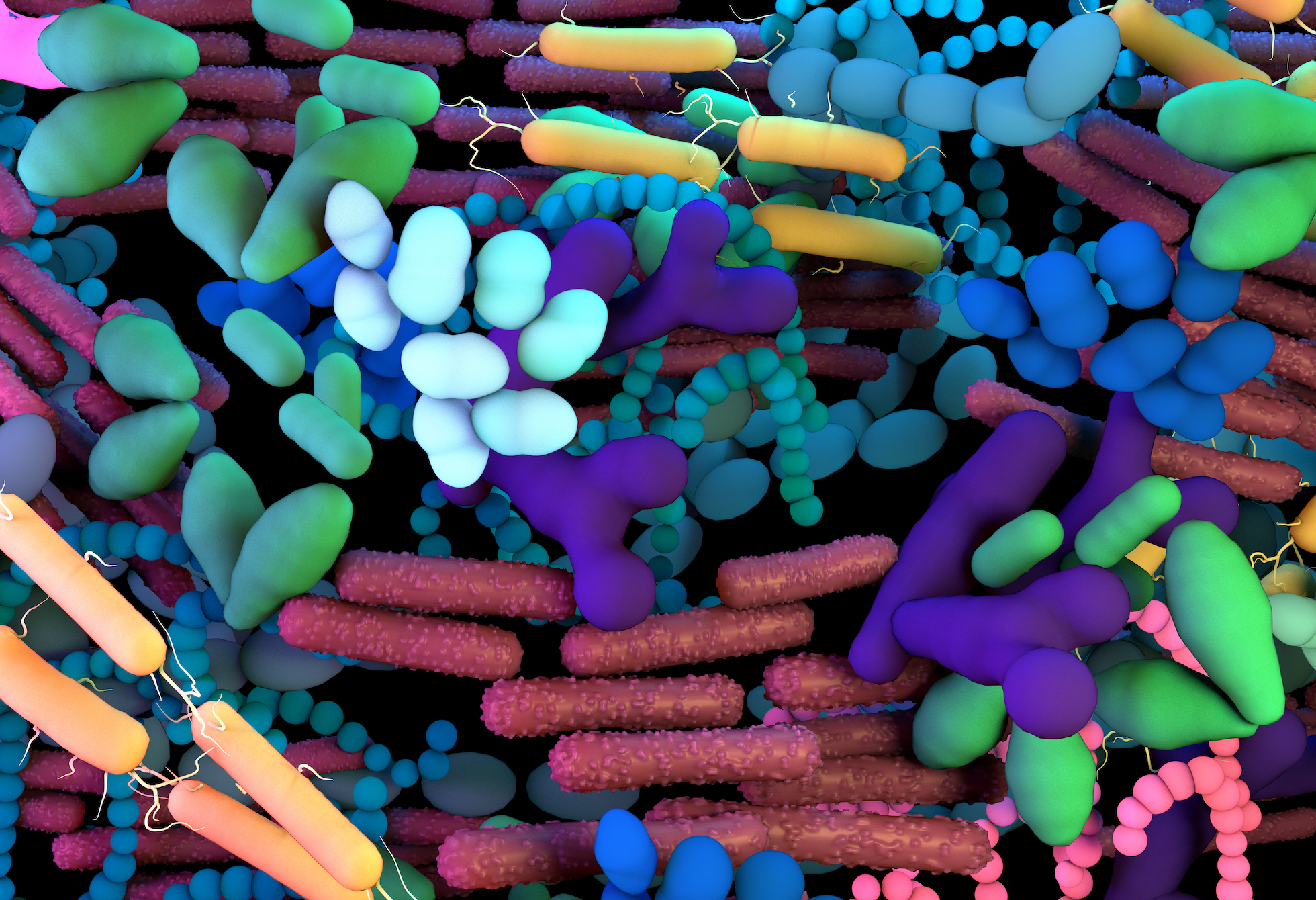

The gastrointestinal tract – which runs from the mouth to the large intestine – contains compounds with neuroactive potential, including neurotransmitters and hormones. It also harbours trillions of microorganisms we call our microbiota, that interact with almost every aspect of our physiology.

Hidden in the gut is also a remarkably similar neuronal structure to the one found in the brain.

While our mouth, stomach and intestines may not necessarily help us think, they could be more connected to our brain and mood than you may have realised.

Arts & Culture

Being open to emotion in art

As the entryway to the gastrointestinal tract, our mouths are rich in microscopic life that are linked with our mental health.

In a first-of-its-kind study, our research team recently found that oral bacteria are associated with adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms. These relationships may be through our endocrine and immune systems, as oral microbiota and mental health symptoms were associated with salivary stress hormones and inflammatory markers.

Relationships have also been found between oral bacteria and schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorder.

But these complex relationships between mental health and oral health are likely to work in both directions.

Young people experiencing depression and anxiety may have poorer oral hygiene routines, as some people living with a mental health disorder experience more difficulty maintaining toothbrushing routines and attending regular dental appointments.

Poor oral hygiene can also lead to changes in oral microbial communities and periodontal disease (like gingivitis), which have been linked to the subsequent development of depression.

And with the mouth being the entryway for our food’s journey into the body, could diet play a role in the relationship between mental health and the oral microbiota?

Arts & Culture

Hey Siri, how’s my mental health?

Symptoms of depression can lead to an excess intake of sugary foods and drinks which can negatively affect oral health, while regular consumption of fruit and vegetables is associated with lower depressive symptoms.

Leafy green vegetables have also been proposed as possible prebiotics that increase levels of nitrate-reducing and oral-health associated bacteria in the mouth, including Neisseria and Rothia. Interestingly, the levels of the bacterial species Neisseria subflava are lower in individuals with schizophrenia and mania.

Stress-induced eating has also been linked to increased unhealthy food intake, which can be detrimental not only to our physical health and oral microbiota but also to our mental health.

Common symptoms of anxiety and depression – like altered appetite, low energy, and physical symptoms – can affect a person’s desire or motivation to cook healthily. And while the links between diagnosed anxiety and depression with diet quality are less clear, sticking to a healthy diet made up of minimally processed whole foods appears protective against the risk of depressive symptoms over time.

This knowledge is valuable given Australia’s overall poor diet quality and highlights the ongoing need for education programs that encourage healthy cooking at home. Population-based interventions to address food insecurity are also critical and could improve access to healthy foods for more at-risk members of our community.

While most of our food is digested by the time it reaches the large intestine, the nutrients we cannot digest - such as complex plant fibres - provide an important energy source for gut microbiota further down our gastrointestinal tract.

Healthier foods support different microbes and metabolic output than unhealthy foods. For example, the fermentation of complex carbohydrates by bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids which, while playing an important role in our systemic health, also lower colon pH.

Arts & Culture

Your face is muted

A more acidic environment can limit the growth of pH-sensitive pathogenic bacteria that may be linked to chronic inflammation (like Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridia).

So, our dietary intake strongly influences the composition of the gut microbiota from our tops to our bottoms. And indeed, both our mental and general health.

We also know that anxiety and depression increase the risk for functional gut disorders and intestinal diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), reflux, and inflammatory bowel disease, and vice versa. Stress can lead to perceivable nausea, bloating, and abdominal discomfort.

While further well-controlled studies are needed – the high rates of co-occurrence between mental health and gastrointestinal conditions may be driven, at least in part, by our gut microbiota.

Anxiety and depression that co-occurs with IBS has been associated with reduced microbial diversity and increased abundance of potentially inflammatory bacteria, including proteobacteria and Prevotella.

Unfortunately, current evidence suggests it’s not as simple as just taking over-the-counter probiotics to alter our microbiota and improve our mental health – at least not yet. ‘Designer probiotics’ are being touted to combat infections, modulate the immune system and even target disease pathophysiology in the future, although we’re still some years off from this reality.

Commercial supplements don’t consider that our microbes can be very different from one person to the next (including those we may be lacking).

Arts & Culture

Mental Health ≠ Wellbeing

If we can personalise future treatments, promising probiotics will need to be carefully examined in the context of whole-body health, including mental wellbeing, and we must better understand their interactions with our non-bacterial microbes – like viruses, fungi and archaea.

For now, a healthy diet and evidence-based psychological treatments remain the best interventions for our microbes and minds.

But there are exciting things happening in technology.

We may soon be able to monitor our health every time we go to the bathroom. A ‘smart toilet’ prototype, developed by scientists at Stanford University, monitors urinary markers and our stools.

There may also soon be smart health mirrors and toothbrushes that integrate mood and lifestyle monitoring through our smartphones.

While there is more research to be done, our ‘gut-feeling’ is not just metaphorical.

The Human Microbiome Project and other large epidemiological studies have made tremendous headway in documenting relationships between our microbial communities and our health. Meanwhile, our studies, including the Bugs and Brains Study and the Victorian Oral Microbiome Study, are working to document the links between our microbiota and mental health here in Australia.

Understanding these complex interactions between our mood, our gut and our microbiota will help us better recognise the multifaceted nature of our mental health.

Part exhibition, part experiment, MENTAL is a welcoming place to confront societal bias and stereotypes about mental health. It features 21 works from local and international artists and research collaborators that explore different ways of being, surviving and connecting to each other. Opening in July 2021, book your free tickets now.

Banner: Microbial Mood by Sophia Charuhas: Installation view, MENTAL: Head Inside, Science Gallery Melbourne/Picture: Alan Weedon