The moral dilemma: Monopoly or Zombies

Games offer an exciting way to explore your morality in a realistic way

Published 7 December 2015

This Christmas many stockings will contain a gift-wrapped copy of Fallout 4, a post-apocalyptic role-playing game. It generated a stunning USD$750 million in sales in its first 24 hours at retail, trumping anything Hollywood has managed.

Open-world “sandbox” role-playing games like Fallout 4 (and the more frequently cited Grand Theft Auto series) have been the lightning rod for media panic about the morality of digital games for over a decade. Critics point to the seeming immorality of this genre – murder, crime and violence against the denizens of its virtual world are glorified – and accuse the game of encouraging such immorality in real life.

Yet while this attracts widespread criticism, the reality is that the crime and violence in Fallout is without any real casualty; if killing a virtual character is murder, we each commit genocide each time the console is powered down.

Depictions of graphic violence are visually repulsive to some, but players will rarely experience a moral quandary when engaged in worlds that pitch them only against machine-generated characters. The oft-cited link between violent games and real violence is unproven, by the way.

Perhaps a more suitable game the defenders of our society’s morality should be attacking is Monopoly. This game (ostensibly suitable for children) encourages family members to aspire to holding an (illegal) monopoly over real-estate and force their opponents (close family members) into insolvency.

I fondly remember ruthlessly bankrupting my elder sister one Christmas when I was eight.

But despite the arguments and allegations of betrayal Monopoly is likely to cause in homes this Christmas, its morality is as unrealistic as that in Grand Theft Auto. Players are granted no moral choice whether or not to bankrupt their opponents and consequently, there is little moral involvement. Realistic morality remains rare in games, and is generally assumed to be at odds with what players seeking escapism want.

However, as the games industry slowly matures, we’re beginning to see more commercially successful games that do explore greater moral involvement.

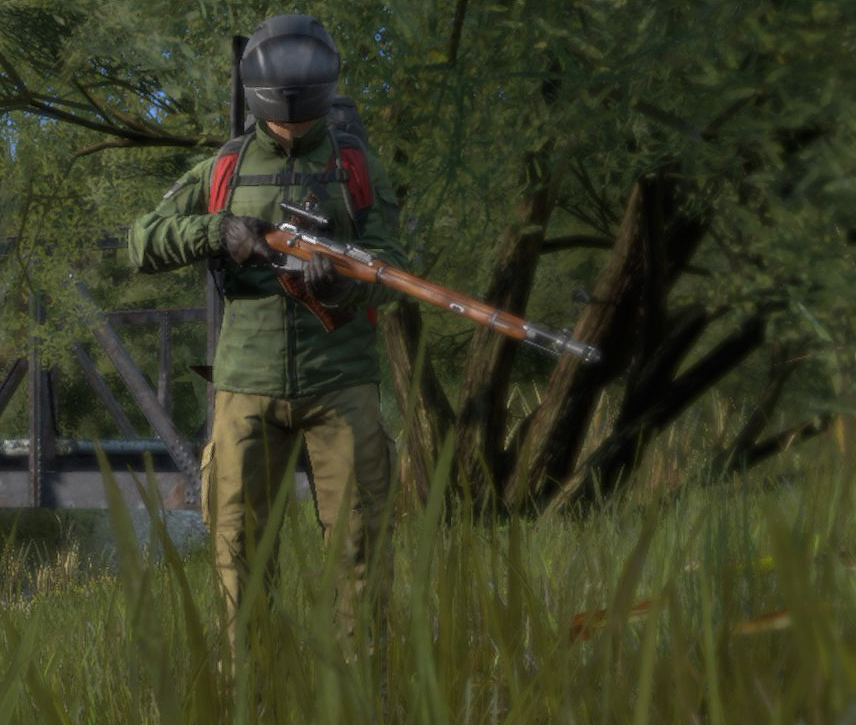

Among them is DayZ, a zombie-themed massively multiplayer online first-person shooter. It is set in a virtual landscape that you share with players from all over the world, in which, unlike much of the genre, on-screen death is highly consequential. Should you perish, all of your advancement in the game is lost, representing hours or even days of effort.

DayZ doesn’t put players into formal teams. Any player you encounter in its ruthless, apocalyptic setting could be friend or foe; a fellow survivor looking to team up to conquer the environment, or a bandit looking to murder you and loot your belongings.

As it turns out, there are players that only hunt others, but there are heroes too; players who dedicate themselves to helping and healing.

But the most fascinating moral experience belongs to those who follow neither path rigidly, but find themselves unexpectedly in anguish over whether to shoot another player (lest they be a bandit) before they get shot first; risk losing your own valued progress, or unjustly steal the progress of another. Real person v real person, with consequences; a massively multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma.

It’s clear from online descriptions that players are attracted to these kinds of more realistic moral dilemmas, which come not from pre-programmed content controlled by the computer or the roll of a dice, but from moral choices involving other people.

DayZ, an independent and otherwise unremarkable title, quickly saw over 1.3 million players. A revised standalone version of the game was released in late 2013, since selling over 3 million copies.

Sci-fi multiplayer EVE Online in does something similar. In keeping with itsdystopic and hyper-capitalistic narrative, developer CCP Games created the possibility for unpunished treachery and betrayal of other players. The number one rule in EVE is “DON’T TRUST ANYONE”.

Perhaps the most celebrated illustration of its moral complexity was the permanent destruction of a powerful and rare spaceship known as a Revenant, worth the virtual equivalent of $9,000 on the in-game market. Rather than out-fighting it in combat - in traditional ‘fair play’, perhaps - it was destroyed by a very human act of betrayal.

A spy, going by the alias BandWidthh, infiltrated an alliance of players and gained sufficient trust among them over six months to be able to lead the $9,000 ship into a trap. Released in 2003, EVE Online recently notched up its 500,000th subscriber.

The mediated (im)morality of EVE enriches the playing experience. It challenges players to have personal moral input; to negotiate for themselves where their own boundaries between right and wrong lie. We are moral beings and games should force us to explore this territory. Yet it remains rare. It is interesting that while high-definition graphical depictions of cutting throats in games like Call of Duty is OK, stabbing someone in the back metaphorically is so lacking in digital games.

EVE and DayZ demonstrate the potential for games to be a medium that offers a rich, moral experience. The interactivity of play and increasing visual realism provides potential for learning more about how people negotiate their own morality in immersive, complex conditions beyond the scope of the lab.

There will always be an attraction to and a place for the game equivalents of a popcorn movie or a trashy novel, and the immoral escapism of an almost meditative murderous rampage in Grand Theft Auto, especially amidst an overdose of seasonal merriment. But greater moral involvement in this medium presents a new way to think about games and how we interact with them.

Banner image: Pixabay

Dr Marcus Carter is an author of Internet Spaceships are Serious Business: An EVE Online Reader, to be released by the University of Minnesota Press in March 2016.