Arts & Culture

Your personal audio tour of the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Michelangelo’s statue of David is the world’s most famous statement on physical perfection, and continues to inspire the next generation of artists 400 years later

Published 30 June 2019

Nothing can compare to the sheer presence and magnetism of Michelangelo’s David.

At over five metres tall, not including its pedestal, this marble colossus dominates everything within the cavernous setting of its current home in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence.

Framed beneath an immense dome and standing imperiously at the end of a magnificent temple-like hallway it glowers down at the visitor with an unsettled gaze that mixes anxious soul-searching with defiant ferocity.

For Michelangelo’s contemporary, Giorgio Vasari, the effect of viewing this giant was so overwhelming it cast the entire history of art into the shade.

“After seeing this no one need wish to look at any other sculpture or the work of any other artist”, he wrote in his landmark account of Italian Renaissance art. And still it seems churlish to argue with him all these years later.

Arts & Culture

Your personal audio tour of the Louvre Abu Dhabi

We need only note the snaking queues of 1.5 million tourists who annually line the block outside the Accademia to see the David effect at work.

And as these tourists patiently wait their turn to pay tribute to the statue’s undeniable aura, that effect is magnified further by a vast emporium of visual merchandise jostling for their attention on the stalls around them.

David postcards, David t-shirts, aprons, underpants, paper weights and much, much more: all this ceaseless recirculation of David’s image throughout the city’s streets and boutiques confirms the continued efficacy of this masterpiece to end all masterpieces, this undisputed star of the Florentine Renaissance.

But how much do we really know about Michelangelo’s David?

Several key facts still have the capacity to surprise, while adding further to our appreciation of its immense artistic achievement.

In the first place, Michelangelo, who in the early 16th century was an emerging artist in his mid-twenties, carved David out of a single block of weather-worn marble that had been previously begun, spoiled and then cast aside by another artist who had tried, and failed, to complete the commission some four decades earlier.

The fact that Michelangelo had to recycle what was in effect a roughed-out block of already botched marble might help explain some of its otherwise puzzling features.

In particular, it might account for the David’s slenderness and top-heavy proportions, all of which give it a slight forward tilt to the body, as if David were about to topple over into our space.

The work’s originally intended location provides another reason – up on the 90-metre high external drum of Florence Cathedral.

The originally anticipated extreme elevation may help explain the feeling of uncanny disproportionality we can occasionally experience when viewing the David – his unusually large head and right hand, his elongated thighs and slightly stretched appearance.

Michelangelo seems to have added all these elements into the design process, while also wrestling with the physical limitations of the stone itself, in order to compensate for the intense foreshortening caused by its originally intended location.

In 1504, after toiling on the commission for three years, Michelangelo finally tore down the brick wall he had erected around the worksite to shield the David from the prying eyes of his fellow Tuscans.

The statue’s dramatic unveiling created such a clamour of universal acclamation that the Florentines thankfully abandoned their plans to hoist it high into the sky. Instead, they convened a panel of leading artists to consider alternative sites (a panel that included Michelangelo’s great rival, Leonardo, who drew a whimsical doodle of the work while listening to the debates).

The committee eventually settled on a location immediately to the left of the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria, then the city’s town hall and still one of Florence’s most prominent public spaces.

Arts & Culture

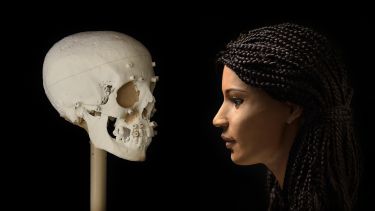

Brought to life, 2000 years later

With this move, the statue’s symbolism changed overnight from a historically remote Biblical prophet, to an ever present, militant civic emblem of the Republic’s ardent desire to withstand external threats, be they from neighbouring Pisa or Milan or any of the other countless enemies to the city’s prosperity that were so much a part of the turbulent geopolitical landscape of 16th century Italy.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the David was finally trundled off to the Accademia along a specially constructed tramline that was designed to combat the problems created by the growing recognition of the new ‘science’ of art conservation.

Here, protected from the elements in a modern climate-controlled environment, the David changed its meaning yet again.

Now it was transformed into the definitive expression of artistic genius, the ultimate, gold-plated museum masterpiece.

And so it has remained to this day, an undoubted inspiration to upcoming generations of artists particularly as a result of the Accademia’s early role as a didactic space for training students enrolled in the adjacent Fine Arts Academy.

From among the countless recent engagements with the work that this setting has inspired we could single out the recent digital video by contemporary Chinese artist Guan Xiao.

Her 2013 David, which was included in the 2017 Venice Biennale, projects a loop of roughly shot YouTube footage of the statue and its reproductions over a deliberately clumsy Karaoke-style soundtrack complete with awkwardly mistranslated lyrics.

Sciences & Technology

When computers make art

In it the artist sings a plaintive ode to the endless conveyor belt of David and its copies, lamenting: “We just don’t know how to see him. We don’t know why we watching” before triumphantly concluding “We can make him disappear so easily” over a culminating montage of smashed Davids.

But of course, as the work reinforces with engaging wit mixed in with a subtle Feminist dig at the whole masculinist shtick surrounding the work, the opposite is actually the case.

Too much is now invested in Michelangelo’s David for it to be going anywhere soon. It will surely continue to tower over us for eons to come – the real thing in a world full of fakes and imitations.

Banner: Getty Images