The rise of the machines: Fact or fiction?

Will we one day have robot overlords? University of Melbourne robotics and artificial intelligence researchers look into the future

Published 23 September 2015

In acclaimed new British science fiction series Humans, state-of-the-art humanoid robots called “synths” are household servants, manual workers, office drones and companions; functional creations that exist purely to make human lives easier. But when some of the robots start to think and feel for themselves, troubles arise.

Science fiction has long been captivated by the idea of the “singularity” – a hypothetical moment in the future when robots, computers and machines can match, or outperform humans at any intellectual task, to the point where they will be able to self-improve, rendering us humans obsolete.

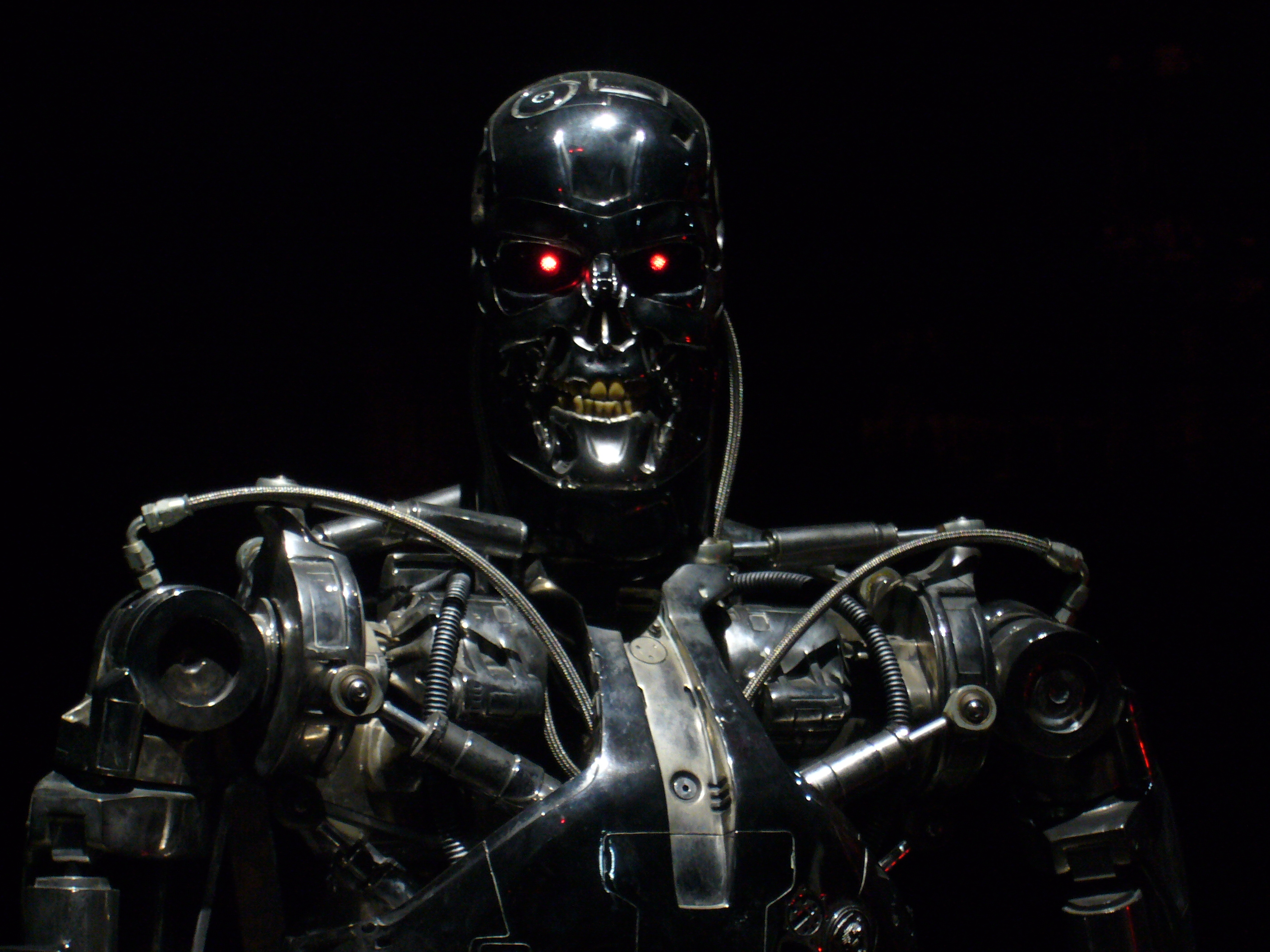

The Terminator films are built on the fear that some day there will be a war between humanity and our robotic creations, which will rise up and turn against us.

In these days of drone warfare, it is a fear that researchers in robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) recognise. In July, an open letter from The Future of Life Institute was presented to the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, calling for a ban on the development of AI weapons – robots capable of killing autonomously, without human control.

The letter was signed by leading AI researchers and scientists including Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, Stuart Russell and thousands more.

But how afraid should we be of the “rise of the machines”? Will the singularity actually happen?

It’s a complicated question, say University of Melbourne researchers Dr Ben Rubinstein, from the Department of Computing and Information Systems, and Robotics Engineer Dr Denny Oetomo, from the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

Both agree that it is possible – just not yet. Roombas might do our vacuuming, and Google seems to know what we’re looking for before we do, but there are still certain tasks that humans can do quite easily that robots can’t.

“I personally don’t think that it’s not possible to have the singularity but I don’t see the path from here to there. I don’t see it happening very soon,” says Dr Rubinstein.

“As a researcher people often ask you at parties, ‘when are the robots taking over?’ This is the boring answer to that question,” laughs Dr Oetomo.

Dr Rubinstein says that a key observation in AI research is Moravec’s Paradox, in which an AI may be capable of high-level reasoning, but conversely finds abstract concepts and very simple sensory and motor tasks extremely difficult.

A child can do a lot of things that AI is not very good at. Children can walk through a room with a lot of clutter. But then AI is really good at playing chess, because this requires high level calculation.

“Sentient” AI that possesses human emotions drives some of the most fascinating science fiction. Spike Jonze’s Academy Award-winning Her followed a lonely man (Joaquin Phoenix), who fell in love with his phone’s new operating system, Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), a highly evolved version of Siri, who seemed to reciprocate his feelings.

But Dr Oetomo says that for the foreseeable future, whatever emotions machines are perceived to display will only be an emulation of the real thing.

It is behaviour that is generated by codes. The machine is not sentient in a way that humans are.

“A lot of very simple toys these days show ‘emotion’. You tickle it and it laughs. You press a button and it cries. But there is also more complex technology, where you allow the machine to act in a guided manner, looking at various factors in order to decide on a response or even allowed to develop an emerging pattern or behaviour. But it’s still all written within the boundaries of a program,” he says.

Dr Rubinstein says he does not know what gives us consciousness. “Perhaps there’s something about the machinery of the brain that we do not know yet how to replicate in a circuit,” he says.

The fact is we’re nowhere close to even emulating intelligence or emotion.

Dr Oetomo and Dr Rubinstein welcome the current debate about autonomous AI and “killer robots”. They say it is leading to important conversations about AI policy, as well as a better understanding of the ethical implications of the AI we currently live with, and how we can make it safer.

“There are more realistic problems than the suggestion that robots will one day take up arms and kill humans,” says Dr Oetomo.

He says something that could happen today might be the example of a self-driving car that sees a pedestrian ahead that it’s likely to hit.

“It must make a choice. The car would have an advanced algorithm to calculate the outcome: if I keep going, I’ll kill the pedestrian, but if I stop suddenly, I’ll kill the passenger,” he says.

“And it will choose, because the programmer has to tell the machine to do something in this situation.”

Dr Rubinstein is now working to make our AI safer, thanks to a research grant from the Future of Life Institute, funded by Elon Musk. He’s one of 37 researchers recently awarded $7m in funding by the Tesla architect and SpaceX CEO to ensure that AI remains beneficial to humanity and avoids potentially dangerous pitfalls.

His project focuses on machine learning – a process in which computers are able to make decisions based on available data and recognition of patterns. Machine learning underpins much of the technology we use every day, from consumer electronics to Facebook, yet it can be vulnerable to attackers who may want to use these powerful tools to turn our AI against us.

“I’m interested in understanding how robust our machine learning is. You need to make your system costly to breach. I’ll be developing new algorithms and software tools to evaluate vulnerabilities in these systems, which is a first step towards secure machine learning.”

Banner image: Dick Thomas Johnson: Terminator Exhibition T-800, Creative Commons.