Arts & Culture

Language for living

In the 21st century, digital publishing has led to the rise of ever-more niche microgenres in books – from Amish romance to NASCAR passion – and it’s changing our literary landscape

Published 13 May 2019

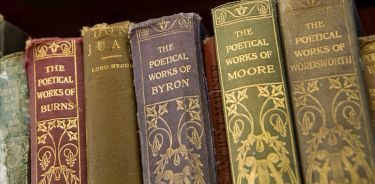

Once upon a time there were two literary genres: tragedy and comedy. I mean there were three genres: narrative, epic and dramatic dialogue. Or let’s paraphrase Monty Python’s Spanish Inquisition: amongst our literary taxonomy are such diverse genres as sagas, ghost stories, westerns, and fables.

Genre has never been a very stable concept — but that hasn’t stopped it shaping the book industry and driving readers’ choices.

The problem is that any definition of a genre throws up complications. Some of these complications are of the familiar ‘this book is cross-genre’ or ‘this writer transcends genre’ variety.

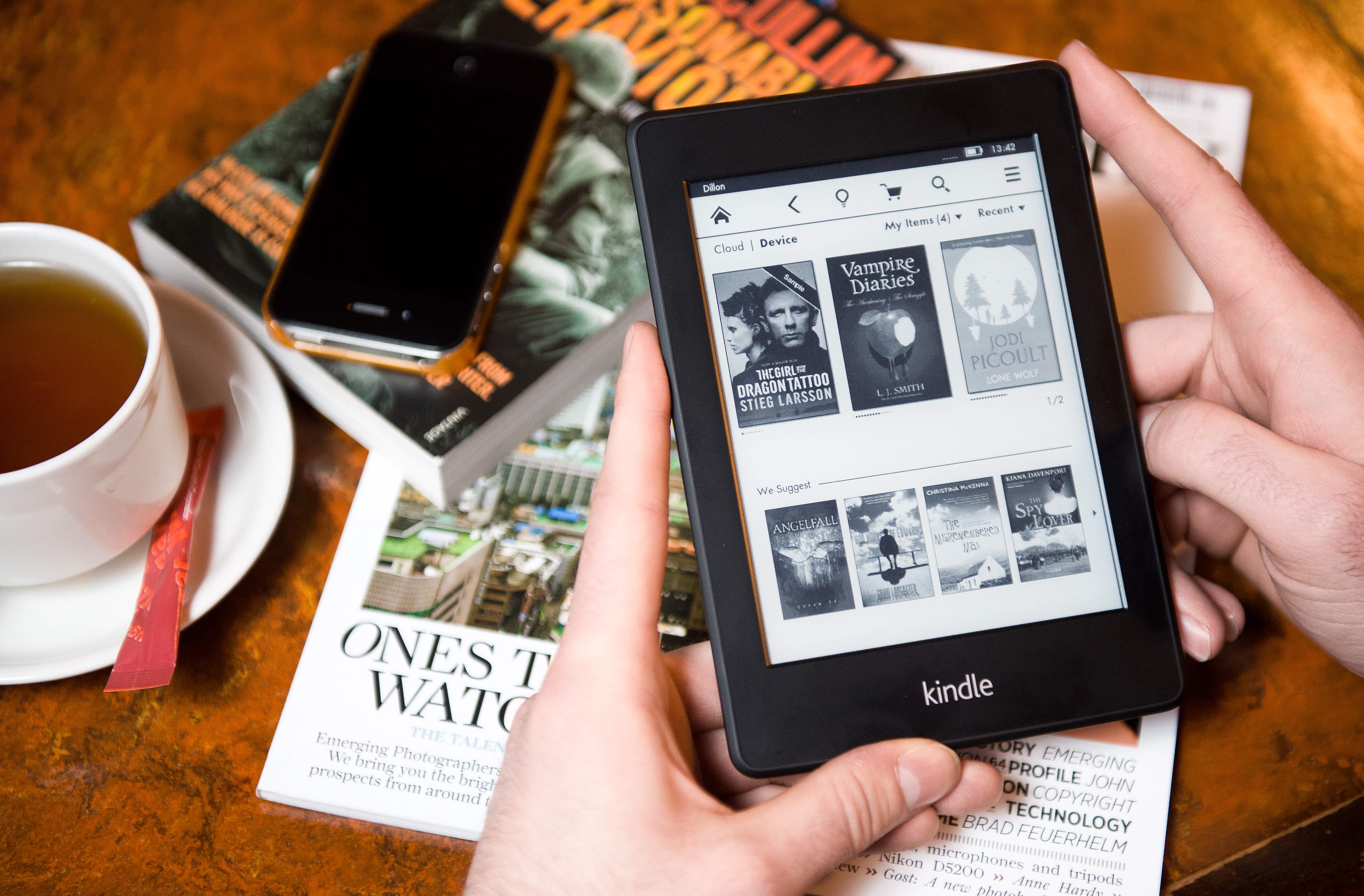

But another complication arises from the new digital publishing environment: the seemingly endless, internal proliferation of subgenres and microgenres.

Our research with the Genre Worlds project has investigated the big three genres of contemporary fiction: romance, fantasy and crime. Each of these genres is growing rapidly, partly driven by self-publishing.

Arts & Culture

Language for living

And genres are important in the world of books: they have effects that are social, textual, and industrial. Genres prompt social gatherings like cosplay at conventions. Genres influence what happens on the pages of books.

Genres are organised by distinctive industrial processes – for example, many romance novelists publish more than two books a year.

Genre fiction has long been divided into subgenres: think of cosy mysteries versus hardboiled thrillers, or paranormal tales versus Tolkien-esque epics. No genre has a more organised system for subgenres than romance.

In the twentieth-century, subgenres were a distribution system for Mills & Boon and Harlequin. Readers would subscribe to a line – like medical or historical romances – and receive books by mail each month.

In the twenty-first century, subgenres have multiplied and grown ever more niche, to the point where many of them are now better thought of as microgenres.

Earlier this century, Harlequin had a line dedicated to Nascar romance; its current website includes a Reader’s Guide to Romance Genres to aid a reader’s navigation through a complex web of imprints, categories, and miniseries like Amish Hearts and Billionaires and Babies.

These can be filtered and cross-searched to end up with titles precisely aligned to a reader’s desires – as niche as medical romances set at Christmas.

In an industry where all publishing is to some extent digital, microgenres, categories and tags all feed algorithms and make titles discoverable. Inside the industry, publishers tag books with BISAC codes, which are updated every year by the Book Industry Study Group in New York.

The 2018 subgenres run the gamut from ‘FICTION/Absurdist’ to ‘FICTION/Women’, via ‘FICTION/Mystery & Detective/Cozy/Cats & Dogs’.

These are attached to the metadata of a book and help booksellers order and arrange their stock.

Online book retailer Amazon uses its own system of categories. For example, Nicole Snow’s novel No Perfect Hero is currently a #1 bestseller in both ‘Romance/Military’ and ‘Romance/New Adult & College’.

Although Amazon doesn’t make it obvious, No Perfect Hero appears to be self-published. It’s often authors, these days, who choose how to categorise their own books.

Thanks to digital technology literature consumers are often on the receiving end of recommendation algorithms, but as producers, we can also try to shape the way the content we write moves through platforms.

In order to understand these publishing dynamics fully, my colleague Claire Squires and I wrote and self-published a short, very niche, novella. The Frankfurt Kabuff, published under the pseudonym Blaire Squiscoll, is a comic erotic thriller set at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The book’s blurb reads:

After a difficult winter, Beatrice Deft is on vacation in Frankfurt during European Autumn, staying at the Hessischer Hof enjoying the quiet of cosmopolitan Germany. When violence breaks out at the stands of far-right publishers across the road at the Frankfurt Book Fair, Beatrice tells herself it isn’t her problem.

But now police patrol the aisles with guns and batons, and queues form at security bag checks, and an old friend begs for her help. There she meets Caspian, the very hot policeman with a baton, and finds herself wondering – what is the secret of the Kabuff?

We first published The Frankfurt Kabuff serially, on the free website Wattpad, where we tagged it not only as ‘comic’, ‘erotic’ and ‘thriller’, but also as ‘autoethnography’, a kind of work where an author uses self-reflection to explore experience.

The Frankfurt Kabuff is currently the hottest title tagged as ‘autoethnography’. In fact, it’s the only story tagged as ‘autoethnography’.

We then uploaded our novella to IngramSpark’s print-on-demand service, where we had to choose BISAC codes. We went with the triple threat of Romance/Contemporary, Thrillers/Political, and Humorous/General. The next step will be refining our keywords to optimise Amazon algorithms.

We don’t yet know how successful our novella will be as it navigates the wider digital world of microgenres – our project is ongoing.

Arts & Culture

10 great books to read before you die

But we do have a preliminary finding.

As author-publishers, we have found that ultra-specific tags and categories can feel limiting, like putting creative work into ever-tinier boxes. But they can also feel generative and exciting, as they suggest new pathways for a book to travel along.

What our self-publishing adventure highlights is that microgenres help books and readers find one another in a global, digital age. Microgenres feed the algorithms that can push books towards niche bestseller charts or reading communities, and then springboard them into wider readerships.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the challenging instability and adaptability of ‘genre’, it is an ever-more powerful tool to help books circulate.

Banner: Getty Images