The rivers run ... but less than we thought

Rain run off into our rivers is often much less than existing models predict and should prompt a rethink on how we will cope with a drier climate.

Published 21 March 2016

South Eastern Australia faces worse-than-expected water shortages under climate change after new research revealed current computer predictions over-estimate the flow of run off into our rivers.

The research found that under prolonged dry conditions modelling predicted twice as much run off into rivers and catchments than was occurring.

The findings are based on analysis of river flows during the 1997 – 2009 “Millennium Drought” and suggest an urgent review is needed of current planning to manage future water resources given expectations that climate change will result in reduced rainfall.

“It means we have to go back to the drawing board with our climate change risk assessment for our water resources,” warns Professor Andrew Western, a water resources expert and deputy head of the Department of Infrastructure Engineering at the University of Melbourne’s School of Engineering.

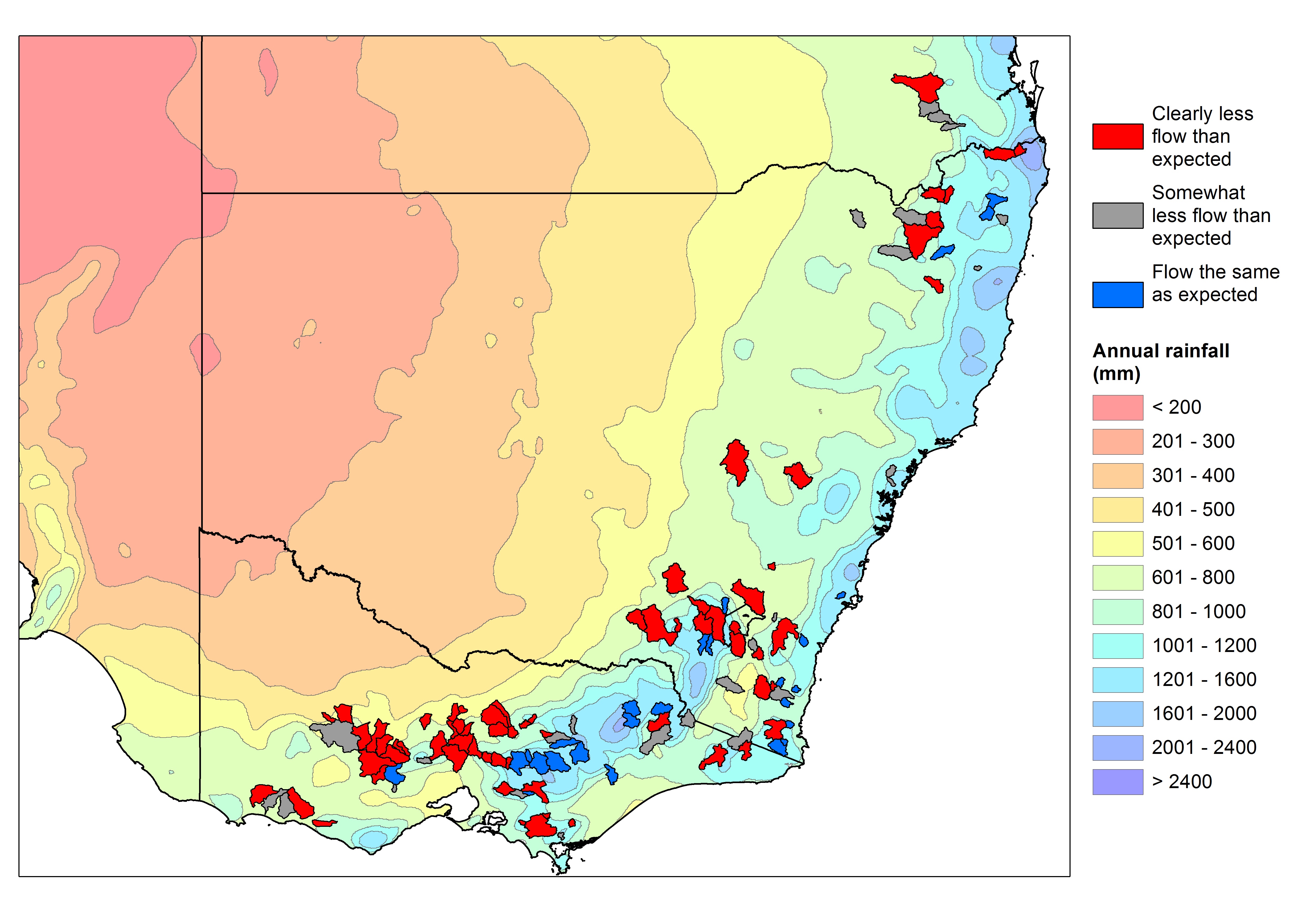

Researchers from the University of Melbourne and the CSIRO used government monitoring records of river flows and rainfall in about 120 catchments extending from South Australia, though Victoria and NSW, and into Queensland.

They compared river flow modelling methods currently widely used to predict water flows with actual monitored river flow data. They found modelled river flows before the Millennium Drought were largely consistent with the actual flows, including during previous shorter droughts. But worryingly, during the long drought they found that actual river flows were much less than what the models predicted in about half of the catchments studied. In the other catchments, the models predicted actual river flows reasonably well during the long drought.

Margarita Saft, a doctoral student in the Department of Infrastructure Engineering, says:

When we predicted the river flow with models in some catchments the models were out by about a factor of two.

“If reduced rainfall under climate change plays out then we will have less water available than we think and this phenomenon may also spread to more catchments if we have low rainfall for a longer period of time,” she says.

The results of their latest research have just been published by American Geophysical Union and follows earlier findings published last year.

More challenges for water management

“If a projected climate change would induce a downward shift in the rainfall-runoff relationship, then stream flow projections using current methods are shown to provide overly optimistic assessments of water availability during a time of declining water resources, further increasing the challenge for water managers,” the researchers write. “Potential modification of catchment processes during an extended change in climate needs to be assessed in order to provide more reliable estimates.”

Professor Western said the research suggests that in many areas the Millennium Drought proved so severe that it altered the capacity of the landscape to produce run-off. He suspects that this may be related to falling ground water levels and that more run off is now being absorbed into the earth and then evaporating rather than being channelled into rivers and catchments.

“During the long drought some of the catchments started to behave differently. They produced much less run off than expected, even after taking into account the lower rainfall. These are the catchments where the models performed poorly during the drought,” says Dr Murray Peel, a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Infrastructure Engineering.

Lowlands worst hit

The worst hit areas where water flows were much less than the models predicted include western and central Victoria and parts of southern and northern NSW. Professor Western said the phenomenon extends to important water supply catchments and that this research will help ensure that water managers are as well informed as possible, helping the community to adapt to climate change impacts.

Ms Saft says the worst hit catchments were generally in the drier lowland regions, rather than the wetter uplands, but it wasn’t a wholly uniform trend with some forested and mountainous areas also suffering reduced flow.

Banner Image: Peter Sunnyside Sunset/Flickr