Sciences & Technology

Secrets from beyond extinction: The Tasmanian tiger

Through a molecular quirk, two distant mammalian cousins evolved to look more like twins finds new research

Published 24 September 2019

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was one of Australia’s most enigmatic native species.

It was the largest marsupial predator to survive until the arrival of Europeans but carried its babies in a pouch like a kangaroo or koala.

Tragically, the last known thylacine died in Hobart in 1936 after a bounty was placed on its head and after decades of hunting by farmers.

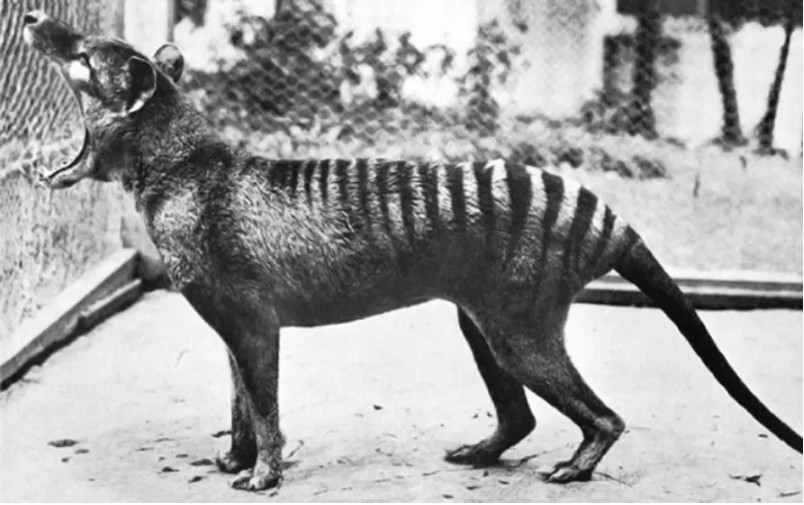

Haunting photographs and film of the last known thylacines and a wealth of museum specimens, reveal an uncanny animal with its wolf head and tiger stripes.

A new study led by Professor Andrew Pask and myself at the University of Melbourne, published in the journal Genome Research, has made the first headway into answering this question by comparing the complete DNA sequences of the thylacine and wolf.

Sciences & Technology

Secrets from beyond extinction: The Tasmanian tiger

And it confirms that the resemblance between the two isn’t just skin deep.

The thylacine and placental canids such as wolves, dogs and foxes, are perhaps the most striking example of convergent evolution. Through this process, distantly related animals can evolve similar forms in response to shared environmental challenges.

Despite having a last common ancestor at least 160 million years ago, these apex predators – who are at the top of the food chain and are not preyed upon by other animals – had nearly identical skull shapes with similar biomechanical properties.

Their resemblance was so evident to early naturalists that they gave it the scientific name, Thylacinus cynocephalus, which could be translated roughly as a ‘pouched dog-head’.

There is even evidence that they filled similar ecological niches, with the arrival of the dingo in Australia implicated in the thylacine’s extinction on the mainland.

In 2018, our team first sequenced the DNA of thylacine from a joey, labelled C5757, and assembled a draft genome sequence.

However, analysis of genes revealed little evidence of molecular similarities or similar pressures imposed by natural selection. This presented a conundrum, as protein-coding genes have critically important biological functions.

Now, by analysing rates of evolution across the genomes of 61 vertebrate species, our research has discovered hundreds of non-coding DNA elements in the thylacine and wolf.

These elements, called ‘TWARs’ (thylacine-wolf accelerated regions), show evidence of natural selection in both species, but lay outside of the much-better understood protein-coding regions of the genome.

In the past, these non-coding regions were considered ‘junk DNA’, but today it is recognised that they play important roles as regulators of genes during development, when most of the traits that make species unique arise.

TWARs were particularly abundant near genes involved in the development of bone, cartilage and muscles of the facial region.

This suggests that natural selection acted in very similar ways in both species, building their shared facial structure by tweaking the same underlying developmental processes.

These findings lend support to one side of a long-running debate in the field of evolutionary developmental biology (known as ‘Evo-Devo’), regarding the relative importance of protein-coding genes and non-coding regulatory elements in evolution.

Paradoxically, the very fact that genes do so much heavy lifting may actually limit their role in adaptation.

Because one gene may be important for the development of multiple structures during development, a mutation can cause collateral damage throughout the body.

In contrast, non-coding regulatory elements typically control a gene’s activity in just one or a few body regions, making them more tolerant of mutations than the genes themselves.

This unique molecular property gives regulatory regions greater evolutionary ‘flexibility’ and increases the chances of acquiring a beneficial mutation without any negative side effects.

So-called ‘junk DNA’ may actually be the primary driver of diversity in animals and could be the key to understanding convergent evolution between the thylacine and wolf.

Unexpectedly, in the course of this work, our team also found that the thylacine and wolf showed evidence of convergence in regulatory elements of brain genes.

This finding was startling, as the brains of marsupials and placentals show major structural differences.

Little was documented about the thylacine’s hunting or social behaviours before their untimely extinction, but these signatures of convergent evolution present the tantalising possibility that these distant cousins may have shared more than just their looks.

Banner: Wikimedia