The story behind every picture

A new book on the history of Australian press photography shows the value of knowing why and how a photograph was taken in the first place

Published 15 August 2016

‘The camera never lies’. When photographs first began appearing in Australian newspapers in the late 1880s, that is how they tended to be promoted. Photography was scientific, objective and neutral, with the camera recording what was visible to the eye and making a faithful visual reproduction.

But even then, the famous saying seems to have been used with a degree of irony. Photography quickly become associated with commerce and art rather than being seen as a scientific recording process. There was an awareness that many factors come into play in how an image comes about – and not least because this was sometimes blatantly obvious in the photographs themselves.

The first breaking news photograph published in an Australian newspaper – in 1888 – was of a train crash at Young, New South Wales. But it was manipulated in the most obvious way possible – not only were several participants posed in front of the wrecked train carriage, but the commercial photographer who supplied it to the newspaper had also painted his name in white on the train’s engine to make sure his intellectual property was given due credit.

That photographer knew, even then, that photographs had a commercial value — especially for newspapers. The 1920s was a ruthless period of corporate expansion in newspapers and the most competitive newspaper owners and executives, including Hugh Denison, Keith Murdoch and Frank Packer, pushed their papers into the modern age by hiring more photographers and placing photographs more prominently within their papers.

The nature of that competition changed forever in September 1922 when Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial was launched as the first pictorial daily newspaper in Australia. The remarkable popularity of that paper, with its pictures-only front page, influenced other newspapers around the country which looked staid in comparison. Even the more conservative broadsheets began popularising their papers with more photographs, and photographs on more prominent pages.

The press photographers who began working in greater numbers for newspapers from this point captured events as they happened but they also staged scenes, rearranged them or had events re-enacted for the camera. For photographers who worked for newspapers, even in the 1950s through to the 1980s, there was an expectation that they had to make events more presentable and fit for publication. They saw this as a skill and a part of the job, that they had to think creatively about how to illustrate news.

This is part of the history Associate Professor Fay Anderson, from Monash University, and I have chronicled in Shooting the Picture: Press Photography in Australia, published by MUP.

In the 1990s, a stronger sense of press photography as representing the ‘truth’ emerged and press photographers tried to avoid intervening or altering a subject as much as possible. While this is still the case today, especially with hard news photographs, other types of photographs, such as portraits of people and social event photographs, still usually require some intervention from the photographer. This can range from asking the subject to move into better light or closer to someone else in the photograph, to requesting they perform some action, or look in a particular direction.

The picture that wasn’t

A common view among press photographers today was summed up by one we interviewed who said that ‘you can’t set up news pictures but most other things are set up’. After all, whenever a photographer points and clicks their camera, every decision they make – from the angle they position themselves as they take the photograph, the lens they use, their shutterspeed and camera settings – all distorts the ‘truth’ to varying degrees.

But press photography itself also had an impact because it generated events to photograph – events that were performative and stage-managed specifically for the camera including ‘the grip and grin’, cheque presentations and the photo op.

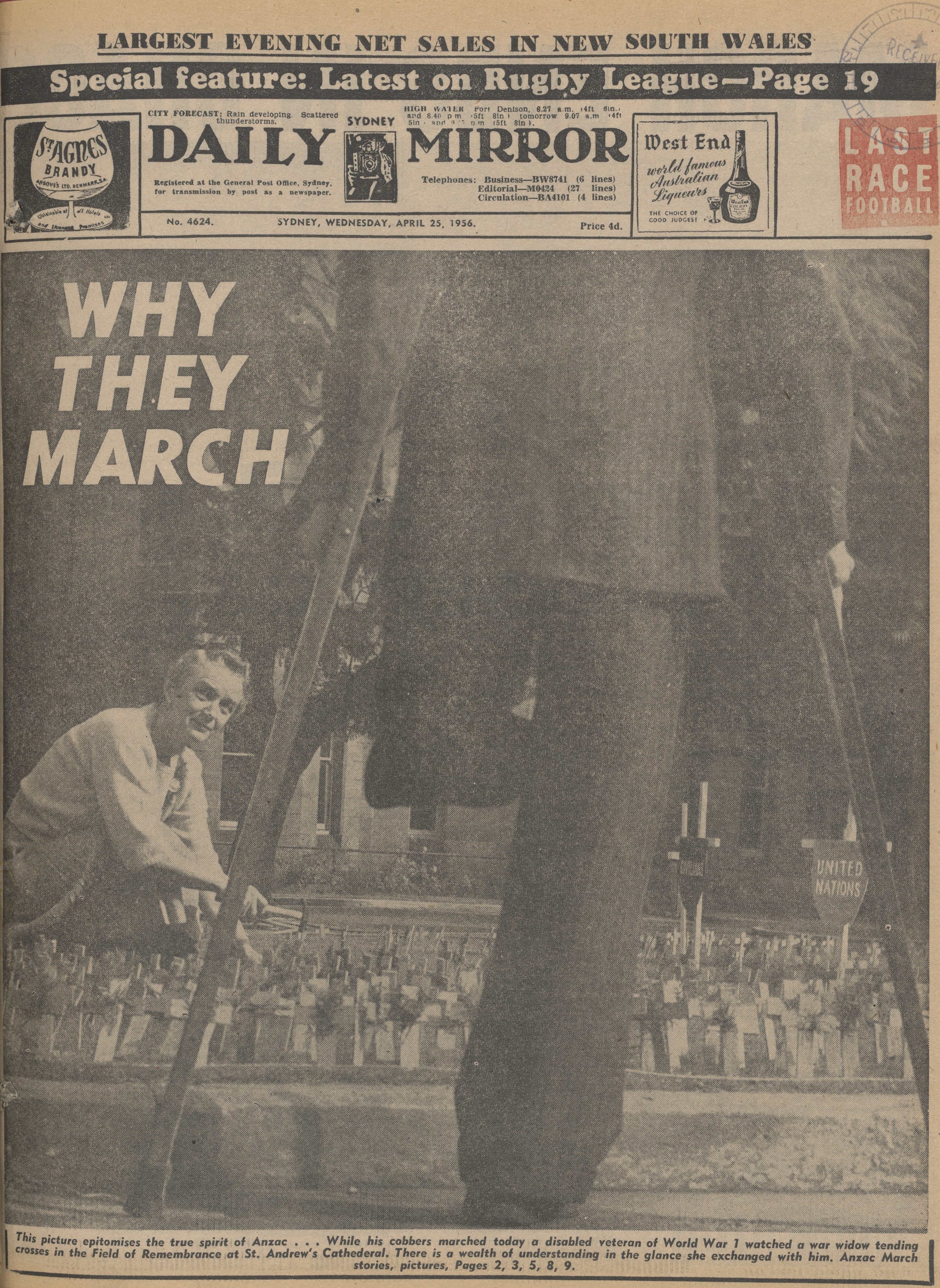

The photograph that won the first Walkley Award for the Best News Photograph, in 1956, raises many questions about the notion of ‘truth’ in press photography.

It was taken by Maurice Wilmott of Sydney’s Daily Mirror and purported to show, in a moving way, an injured veteran remembering his fallen comrades on Anzac Day. But it was the result of Wilmott’s editors directing him to get something unusual that day instead of the standard images of the Anzac Day march.

Wilmott found the one-legged man drinking out of a bottle with his mates and offered him a ‘couple of quid’ if he would pose in the photograph. The man agreed so long as his face would not be shown. After the photograph was taken, Wilmott asked the man which war he had lost his leg in. Neither, the man told him. He had lost his leg in a tram accident in George Street, Sydney. Wilmott was not happy but thought the photograph still conveyed the right message. Interpreting meaning is one thing but, in this case, the caption under the front page photograph blatantly misrepresented what the image showed by describing the one-legged man as ‘a disabled veteran of World War I’.

Among the sixty press photographers we interviewed for the book, there were different views about how far a photographer should intervene in events. Some of the older photographers, those who were trained to illustrate news in an engaging manner, said they find the more literal style that press photographers use today often looks bland and unimaginative.

What mattered most to those veteran photographers was the impact of an image, not what they saw as fairly spurious questions of authenticity. Staging was regarded as a skill, and early photographers were valued for ‘thinking outside the box’ and ‘making something out of nothing’.

On the other side of the generational divide, younger and current press photographers sometimes look back at older photographs that were highly staged and think that style can now sometimes look too insincere and old-fashioned.

Along with photography styles and photographers’ attitudes, audience member expectations have also changed over the years. For the viewer of a photograph today there is a much greater scepticism about the notion of photographic veracity. Photographic images are understood more as constructs than absolute truth. This means that one of the central issues at stake now is how a photograph is presented to readers. Misrepresenting an event is an abuse of trust and discredited images lose their impact.

Viewers want to know more about the context of a photograph today in order to understand how it came about. Where once a powerful image tended to stand on its own, we now see that powerful photographs – like the photograph of the drowned three-year-old asylum seeker Aylan Kurdi, the victim of the Brussels airport bombing, the kangaroo cradling its dead mate, or the Black Lives Matter protester standing in front of police – all tend to be followed by stories about both the subject of the photograph and the accounts of the photographer about how they took it. Notably, many of these powerful photographs were taken by professional photographers rather than ‘citizen photographers’.

In an age when we know that thinking of a camera as a neutral observer is naïve, while we remain open to their impact as powerful images, we also value knowing the stories behind the photos so we can understand how they were captured and why.

Associate Professor Sally Young and Associate Professor Fay Anderson, from the School of Media, Film and Journalism at Monash University, are the co-authors of Shooting the Picture: Press Photography in Australia. The RRP is $45 and it is available at all good bookstores. It can also be ordered through MUP here.

Banner image: Photographers capture the action during the swimming finals at the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games on on August 8, 2016. Picture: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images