The woman who changed the lives of millions

How doctor and nun Mary Glowrey was ahead of her time in expanding healthcare in India, putting her on the path to possible sainthood

Published 6 December 2016

It is unlikely many of us have heard of Sister Mary Glowrey, but that’s going to change. An outstanding humanitarian and medical professional, the Catholic Church has put Dr Glowrey on the path to becoming Australia’s second saint, after the canonisation of Sister Mary McKillop in 2010.

So why does this country girl, born in 1887 in the Victorian town of Birregurra, deserve our attention today, let alone deserve consideration for sainthood?

A humanitarian, advocate for women’s rights and a systems thinker, Mary devoted her life to improving healthcare in India, where she expanded a small mission into a full hospital that cared for 637,000 patients between 1927 and 1936. She went on to establish health care systems and institutions that now look after more than 21 million people annually.

Inspired by the church’s teachings on social justice, Mary sought to change society not just through prayer but action. Her profound faith, compassion for others and brilliant intellect, juxtaposed with a humble and shy nature, led her to push the boundaries of the roles that women could play in society.

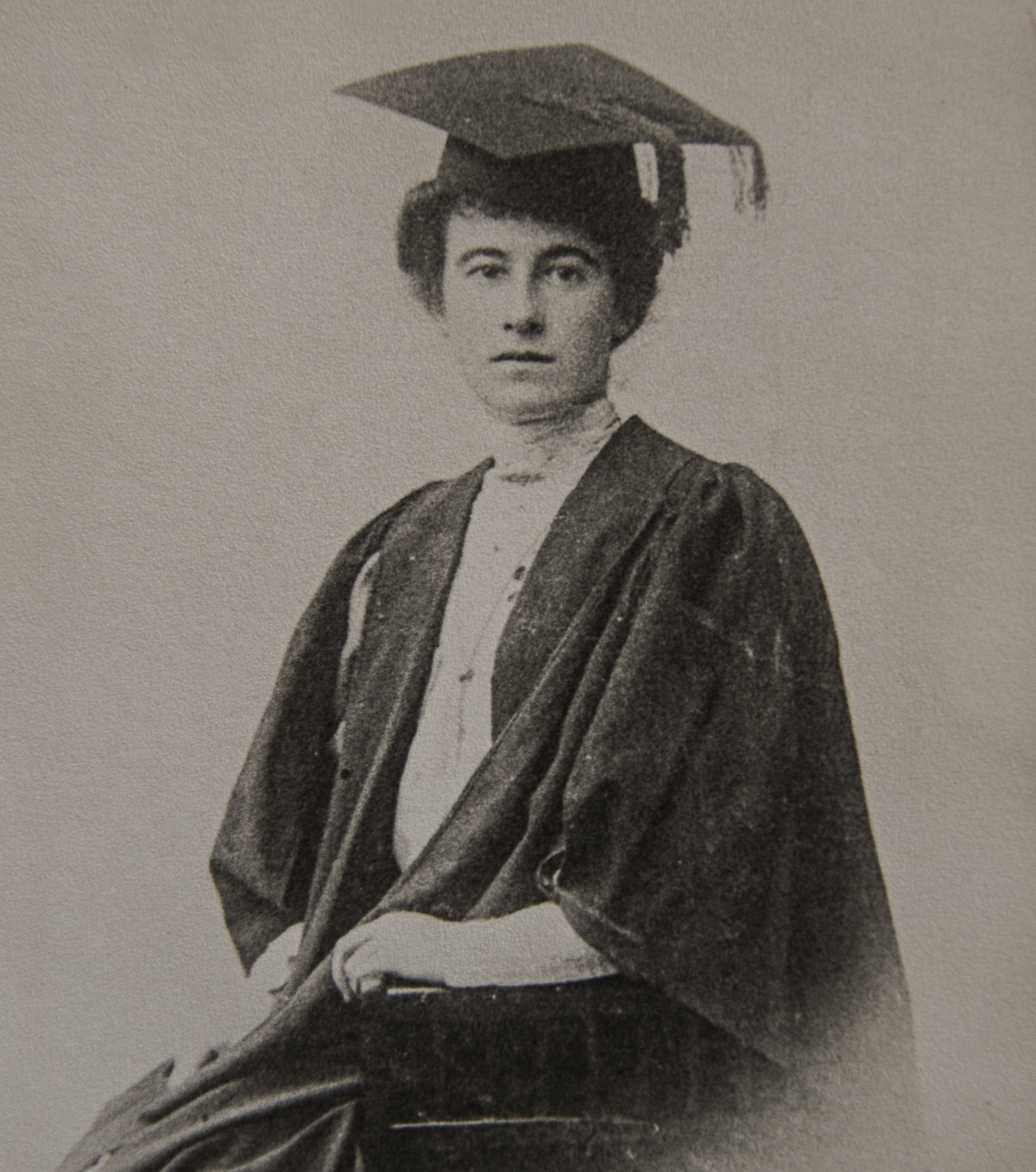

In 1904 she was awarded a scholarship to Ormond College to study for a Bachelor of Arts. But she switched to medicine in early 1906, a time when there were few female medical students at the University of Melbourne.

In her autobiography Mary writes that when she first thought of switching courses a doctor warned her “the study of medicine would deprive me of all womanly dignity”.

Before studying medicine, her favourite subject had been Greek poetry and she fondly remembered the enthusiasm of her tutor at Ormond College.

“In the strength of the breeze he himself created, his University gown used to float behind him as he strode to and fro before us, exclaiming ecstatically: ‘Shakespeare could not have done better; he could not have done better’,’’ she wrote.

Mary began her medical career at the newly-founded Clinical School at St Vincent’s Hospital in 1910. However, at the time, no medical residency positions were available for women in Melbourne so she moved to New Zealand, where she was the first woman to be granted a medical residency.

When Mary returned to Victoria, she focussed on improving the health of underprivileged women and children and founded the Catholic Women’s Social Guild. She supported this work herself through her appointments at St Vincent’s Hospital, the Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital and her private practice. Long before bulk billing she was treating the unemployed and impoverished free of charge.

But it was her work in global health which is perhaps most inspiring and is one of the key aspects of her life which is being explored as part of her cause for canonisation.

After reading about the appalling death rate among babies in India Mary responded by becoming a medical missionary with the congregation of the Society of Jesus Mary Joseph as a nun to work in Guntur, in India’s rural southeast. She would stay working in India until her death in 1957.

One of the first hurdles Mary faced was that neither priests nor nuns were permitted to practise medicine at that time. Fortunately, Pope Benedict XV granted special permission for Mary to practise medicine, making her the world’s first nun-doctor missionary.

Ahead of her time

Mary’s approach to global health was ahead of her time and was more consistent with a contemporary health-development paradigm. She was what we today would call a systems thinker, in that she developed processes and structures to promote efficient and sustainable healthcare delivery to the poor.

For example, perhaps inspired by the sheer size of the task in improving health care for India’s burgeoning and needy population, she pioneered institutions to educate Indian doctors, nurses, midwives and pharmacists. She was instrumental in establishing St John’s Bangalore, one of the most respected medical colleges in India, which today trains thousands of doctors, nurses and allied health professionals who work across India.

One of Mary’s most important contributions to developing a more efficient and effective system was her work in establishing networks and collaborations. Those of us in global health now take this for granted in healthcare planning in low and middle-income settings.

In 1942 she established the Catholic Hospital Association of India (CHAI), which stands as perhaps her most enduring and impacting legacy. CHAI was created to promote the health of the marginalised across India. It has now become the world’s largest health network, boasting 3518 member institutions, including 2263 health centres, 417 secondary care hospitals, 183 tertiary care hospitals, 200 social service societies, five medical colleges and 120 nursing schools. There are now over a thousand sister-doctors across CHAI following in Mary’s footsteps.

While it is up to the Catholic Church to judge whether Mary can be credited with a proven miracle, I would think bringing and keeping together so many partners must in itself be miraculous.

Mary was also deeply respectful of India, its people and their systems, and this set her apart from the prevailing attitudes demonstrated by many of her Western contemporaries. She aimed to build on existing systems and approaches to health rather than to merely replace them.

In recognising Mary’s tremendous contributions to health, St Vincent’s Health Australia and the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne have established the Sr Dr Mary Glowrey Scholars Program to support health professionals from CHAI to gain training and skills in Melbourne. CHAI director Rev Dr Father Mathew Abraham is currently in Melbourne to inaugurate the new program.

Whether or not you are Catholic (and I am not) Mary was a Victorian woman of whom all Victorians can be immensely proud. We can learn from her passion and approach to global health. She should be an inspiration to many of us who want to use our skills to make a true and lasting difference in this world.

Mary was recognised by the Catholic Church as a “Servant of God” in 2013, the first of four official approvals towards sainthood.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance in writing this article of Robyn Fahy of the Catholic Women’s League of Victoria & Wagga Wagga.

Banner Image: University of Melbourne, Senior Anatomy Class 1908. Of the three women, Mary Glowrey is on the right. Picture: Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne.