Three reasons Better Call Saul works: A scriptwriter’s perspective

What makes a sequel work? Vince Gilligan’s portrait of the legal shyster proves there is life beyond Breaking Bad

Published 19 August 2015

How do we become the people we are?

In AMC’s Breaking Bad we saw how Walter White ended up Heisenberg, how Jesse Pinkman ended up more broken than he began. But what about Saul Goodman, Mike Ehrmantraut, Tuco Salamanca?

Many successful shows spawn sequels. Producers and networks, keen to capitalise on having hit the jackpot, are loath to let go of the winning formula even after the final episode of a high-rating, well-loved show, and they follow the inevitable path of What Comes Next? This thinking gave us Joey, Frasier, and Joanie loves Chachi. Some are successful; some leave us wishing we’d never set eyes on them.

Vince Gilligan – who is repeatedly proving himself to be an inventive story-telling mind – chose the other direction: How Did We Get Here? Building on the success of Breaking Bad, which he wrote and produced, and rewarding its devoted viewers, he’s spun off a prequel: Better Call Saul. And it’s excellent.

We’re a week away from the finale of season one. The debut episode became the most-watched TV series premiere (for a key demographic) in US cable history, with 6.9 million viewers, when it aired in February. It has claimed further viewing records since.

Why does it work so well? Three reasons: character, character, and character.

Gilligan understands that story comes from character, so he develops characters who give endless story, who have enough complexity and internal logic that they can twist and turn and baffle and surprise and still remain in character.

Well-conceived characters are icebergs – we the viewers see about 10% of the whole. Most of what the writer knows about them lies beneath the surface, and it’s these histories and drives that cause complex, interesting characters to act the way they do, to surprise and confound us, to compel us to watch them in every episode they appear.

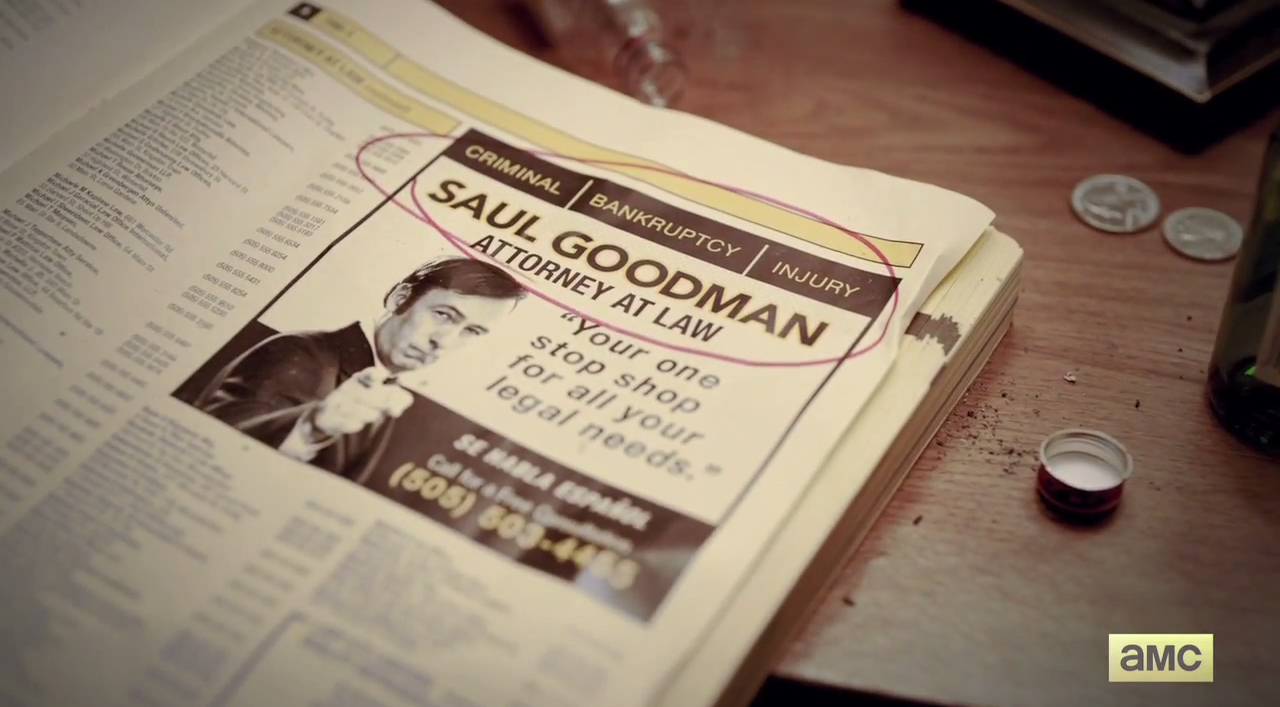

Saul Goodman is one such creation. He exploded onto our screens fully formed as the fast hustling, ambulance chasing lawyer inhabiting a brilliantly, bafflingly over-the-top office. Who decorates like that? How on earth did this creature emerge? In Better Call Saul we find out.

We also discover how he met his fixer, Mike Ehrmantraut. And where he first crossed paths with crazy Mexican drug-lord Tuco Salamanca. Better Call Saul is a series of meet-cutes, but not of the romcom kind, more the deeper-into-trouble variety. Saul’s world is being built and, in however many seasons Better Call Saul runs for, we’ll avidly watch Jimmy McGill transform into Saul Goodman, the man Walter White better call.

Another of Gilligan’s talents as a writer is raising the stakes. We saw this repeatedly in Breaking Bad when he put Walter and Jesse under ever-increasing pressure, in seemingly impossible life and death scenarios, and they continually survived.

And not through some random act of god, but from seeing an opportunity where no one else did, through deal making and fast thinking, through chemistry.

Solutions came from character and story logic. They surprised us but they didn’t perplex us. In the world Gilligan had created they made sense. I once heard Gilligan say in an interview that he strives to have seven surprises in every hour of television he writes, and surprise us he does. Repeatedly. Satisfyingly.

And the stakes were not only raised for Walt and Jesse, but for Skylar, and Walt Jnr, for Hank the DEA brother-in-law. Thorough and complex characterisation plus tight, surprising plotting equalled devoted fan viewing.

Gilligan has chosen to go back six years with Better Call Saul, to 2002. To a time when Walter White was a law-abiding chemistry teacher, and Jesse Pinkman was still at high school, most likely paying no attention to Walt’s teaching and failing his chemistry exams.

One of the great joys of this choice of 2002 is that at the end of the 10 episodes of season one, we’ve still got five years of Saul’s evolution to explore. A second season of 13 episodes had already been commissioned before the first season aired. Plus the opening scenes of series one promise even more than six years of prequel – could there be life for Slippin’ Jimmy post-Breaking Bad?

In those opening scenes, Jimmy then Saul now Gene is living undercover in Omaha, Nebraska managing a Cinnabon store and looking mighty nervous that his old life is going to find him.

The viewers are more nervous that it won’t. Here’s one sequel I would have complete confidence in.

When we’ve finished watching Better Call Saul I’m betting many of us will turn back to watch Breaking Bad again, from beginning to end. Saul is a spin-off series that adds layers and richness to its parent show. Where so many spinoffs leave us with regrets and the wish we’d never fallen into their arms with so many hopes, Better Call Saul is so far giving us exactly what we want – familiar characters involved in great stories with an added frisson of knowing where it’s all going to end.

Vince Gilligan, please don’t ever stop writing. You’ve got a lot to teach us about storytelling, about the human animal and about life.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.