Trailblazing for women in science

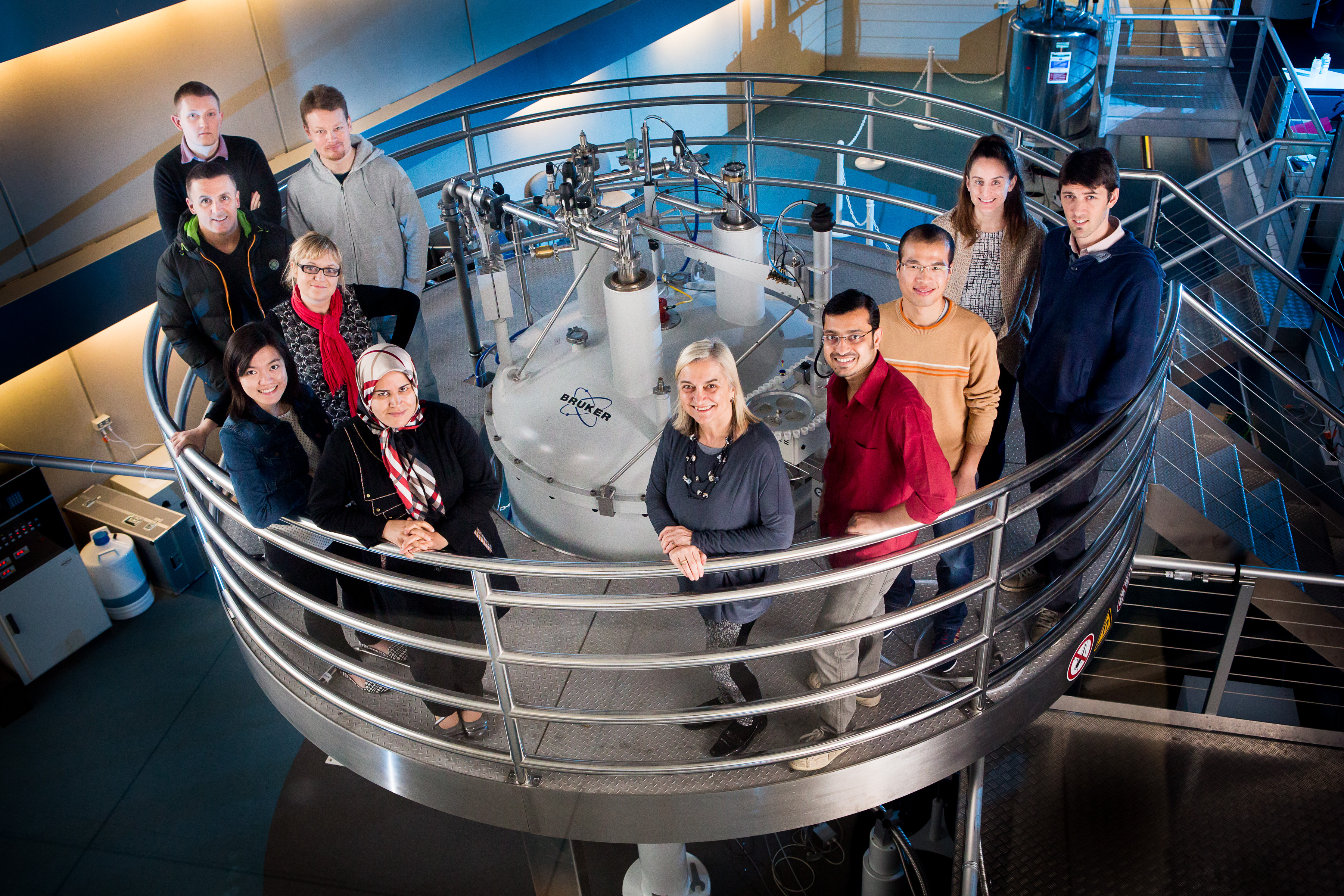

The first female chemistry professor in Victoria, Frances Separovic forged her career against the odds, and has just been named a ‘trailblazer’ on the Victorian Honour Roll of Women

Published 11 March 2018

At high school I did maths and science because my parents didn’t let me go out with boys and this was one way to meet them. I didn’t realise that girls weren’t supposed to do maths or science and it was my teacher Mrs Ashman, who encouraged me and told me I was good at school.

Although I’d been dux of Broken Hill High School, then the largest high school in NSW, and had started studying at Sydney University with the choice of two scholarships, I felt completely lost in the middle of the big city and dropped out within three months. I joined the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) to work as a junior technician in the microbiology lab.

It was when I had my first child that I realised that I wanted more out of life, both for him and for me – so I went to TAFE. I continued my studies with a Bachelor of Arts (Maths and Physics) at Macquarie University part-time, while my parents helped look after my son. Then, while working full-time and studying part-time, I completed my honours in Electron Spin Resonance (ESR), which is like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and really enjoyed it. My colleagues at CSIRO encouraged me to do a PhD in physics at the University of NSW. By the time I had finished TAFE, Honours and PhD, my son was 18 years old and grown up.

I took a leave of absence from CSIRO and received a fellowship from the National Institutes of Health in Washington between 1994 and 1995. I loved working there; I liked the basic science ethic and the culture of curiosity about how things work.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is everyday quantum mechanics – it’s beautiful! These remarkable machines make it possible to analyse the building blocks of matter. I use them to study biological membranes and the molecules embedded in them to gain more understanding of amyloid plaques, which are a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, and to develop new improved peptide-based antibiotics.

An NMR spectrometer tells you how far apart the atoms are; their distance and how they are connected with each other; what’s connected to what, through what kind of bond.

Its name yields clues to how it works. ‘Magnetic’ refers to the fact that these machines use powerful superconducting magnets: niobium-tin coils, that when extended, reach up to 100 kilometres in length. These coils are compressed inside a sealed metal chamber, encased in a vacuum and kept at a temperature of -269°C.

Radio frequency waves excite the nuclei in atoms and molecules, causing them to resonate and give off a unique frequency, which can be used to identify them. The data appears as spectral readings on a graph.

There are a number of proteins that span cell membranes that I’m interested in, particularly where they have some antimicrobial function, such as maculatin in the skin of the Australian Green Tree Frog.

Sciences & Technology

Miss Lambert’s Thylacine skull

Deep down, I just want to know how things work. Once you know how something works, then you can fix it, or make it better. When I returned to Australia in 1996, I saw an advert for a Senior Lecturer and Reader in solid-state NMR at the University of Melbourne.

The job looked like it had been written for me and I applied. I was offered the position of a Senior Lecturer at a Reader’s salary. Insulted, I turned it down, telling them I wanted the title and the recognition. And then I was offered the position Associate Professor and Reader.

That’s how I became the first female Associate Professor and Reader at the University of Melbourne. The Head of Department, Bob Watts became my champion. In 2005, I became the first female Professor of Chemistry in Victoria, and only the third in Australia. And in 2010, I became the first female Head of Department in the University’s School of Chemistry.

Now I am the first female Deputy Director at the Bio21 Institute.

Professor Separovic has received many honours in her career, including the ASB Robertson Medal for Biophysics in 2009, the Australia & New Zealand Society for Magnetic Resonance Medal in 2011 , and the International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry Distinguished Woman of Chemistry/Chemical Engineering in 2017. In 2012 Frances was the first woman chemist to be elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science. She was also elected a Fellow of the Biophysical Society, and an International Society for Magnetic Resonance Fellow.

-As told to Florienne Loder

Banner image: Getty Images