Discussion & Debate

‘I am watching the US enthusiastically leap into an authoritarian regime’

There’s a parallel between ancient Rome and America’s modern republic and it doesn’t bode well for the future of the US

Published 31 March 2025

As political commentators scramble to comprehend just what is happening in the United States, one ready parallel keeps coming up.

Time and again President Donald Trump’s regime is compared to the ancient reign of the Caesars, the Roman emperors synonymous with unrestrained power and excess.

The comparisons are understandable.

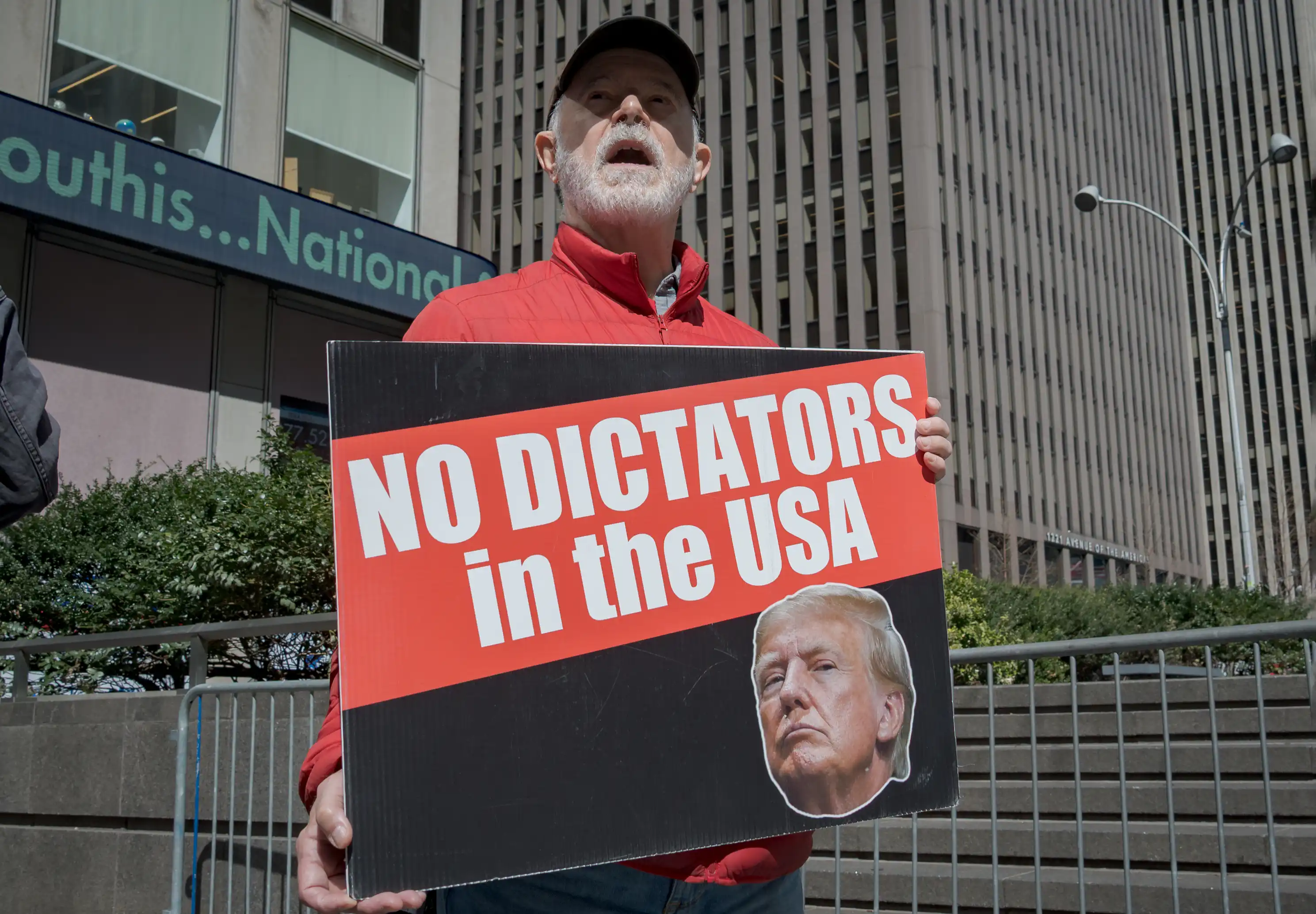

The United States confronts a tyranny unprecedented in its history: the replacement of the rule of the people with the domination of one man (and his wealthiest friends).

Just this week, Trump has again invoked the idea of securing a third presidential term in defiance of the American Constitution. He has previously spoken of being a 'dictator' and signed off social media posts with references to himself as 'king'.

British author and historian Tom Holland, best known for co-hosting the popular The Rest is History podcast, recently noted, the Caesars have a strong resonance in the reign of Trump – their whims and egos once also governed the lives of millions.

But the comparison between Trump and the Caesars is misplaced. Trump is no Caesar – he wishes.

Discussion & Debate

‘I am watching the US enthusiastically leap into an authoritarian regime’

There is an alternative parallel between ancient Rome and America’s modern republic that has greater resonance, with even greater consequences for understanding the extraordinary descent into autocracy we’re seeing in the US.

It’s not the story of how flagrantly the emperors of Rome flaunted their rule, but rather, the processes through which the emperors came to power in the first place.

For those who cherish the promise of America’s democracy, it is the fall of Rome’s republican experiment that provides the clearest parallels, and the most severe warnings as to what might loom ahead.

The Roman Republic was beset with fatal contradictions at its very founding. Rome was founded as a city ruled by kings.

The mythical Romulus, from whom the city took its name, was followed by a dynasty of Tarquins (also steeped in historical mystery). When their capricious bouts of cruelty grew too much for the city’s noble class to bear, the Tarquins were overthrown.

A republican order emerged, though it was one that remained attenuated by wealth and power. The city’s aristocracy had resorted to regicide to live free of the tyranny of one man. This included their freedom to impose their collective tyranny on others.

Political power was controlled by the wealthiest and dominated – politically, economically and socially – by men.

The expanding empire’s economy was powered by slavery. Though, as British classicist Mary Beard noted, Rome did have an expansive understanding of the bounds of citizenship.

What emerged was an uncertain experiment in rule by the ‘people’, however hazily defined, through new institutions and conventions intended to mitigate the power of any one person.

Politics & Society

From the ‘royal we’ to ‘me, me, me’

Hence, Rome’s Senate, designed to provide wise counsel to the city’s magistrates. Hence the rule of the Consuls – two men elected to effectively share executive power for one year.

The contradiction was clear from the beginning. Non-aristocratic plebian orders (well, the men at least) rebelled against their exclusion from the rule of the city.

A ‘conflict of the orders’ resulted in an expanded political role for plebians: new assemblies, representatives and forms of mobilisation. Their demands were accommodated by the riches of a growing empire.

Even as the republic’s power and territorial reach grew, it was tenuous – the product of historical accident and the conscious intervention of social forces. It draped itself in a mythos of destiny and grandeur to provide the coherence it naturally lacked.

In 146 BCE, Roman legions finally conquered Carthage, the only immediate rival to Rome in terms of reach and power.

That same year, legions sacked the wealthy Greek city of Corinth.

This was a turning point.

Rome was not a world power, but it was the undisputed power of its world. Across the vast stretch of the Mediterranean, Rome was not always in direct control, but it was hegemonic. Beyond its bounds, rivals loomed, but none with the power of the republic.

A great empire had been conquered, a new order installed. But who was to enjoy the benefits of its spoils?

The Roman elite turned to plunder.

The immense wealth the empire generated was concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. It was feared that Rome had lost its mission, its reason for being – becoming little more than an extortionist racket.

Politics & Society

Trump’s victory will recast American politics in his own image

We need to understand this as the context for all that came between the fall of Carthage and Caesar’s ascent to power in 49 BCE.

What emerged was the age of the ‘great men’ and dictators. Popular generals who bound their legions to them with oaths of personal fealty and fought over their visions of what Rome was supposed to be, but equally, they fought for prestige and power. Their share of the spoils.

They treated the conventions and norms of Roman politics with contempt. Rendering long-held beliefs and certainties irrelevant in this new age.

There were Gracchus and Gaius, brothers who secured themselves the vaunted position of Tribune of the people, a powerful post that they used to rival the authority of the Senate and its Consuls. Gracchus, in defiance of tradition, stood for the office twice.

Their programs of land redistribution and subsidised grain were denounced by the aristocratic elite as what we would call today, populism.

This defiance was ruthlessly quelled.

Then came Sulla, the general who marched his legions on Rome. Stripped his enemies of power and ensured his appointment as dictator.

Though he claimed restoration, Sulla remade Roman politics. Proscription lists were pasted over the city. Those whose names appeared, Sulla’s enemies, knew their lives were forfeit if they did not flee.

Soon, Sulla’s cronies were pasting the names of those whose primary sin was having wealth that was coveted. Murder had been cemented as a tool of Roman politics.

One of those listed (though for a minor infraction) was a young Julius Caesar. Caesar learned his politics in the age of Gracchus, Gaius and Sulla.

A new culture of politics dominated Rome. Populist mobilisations based on immense wealth, position secured by military arms, the capacity to purchase public affection and the ability to defy once-cherished conventions with impunity.

Julius Caesar was a near-perfect expression of all these tendencies.

Caesar rose to prominence through his willingness to use wealth (often incurred at the cost of great debts) to buy popularity. He cemented this through military prowess, an expansion of Rome’s borders deep into Gaul (modern France) at what would be considered today a genocidal cost.

He demonstrated his willingness to use violence as an ordinary tool of politics. And underpinning it all was a populist program of land redistribution.

Caesar’s great rival was Pompey the Great, a similarly mercurial personality who flagrantly flouted Rome’s political conventions in his rise to power.

The great men fought out their ambitions. What was left to restrain them?

It was not just clashing personal ambitions, but the republic’s fundamental contradictions that led to the civil war from which Caesar emerged victorious.

Caesar did not destroy the republic when he anointed himself as dictator for life. Nor was the republic saved when he was struck down by a group of senators determined, in their eyes, to prevent a return to the tyranny that reigned during the rule of the Tarquins.

The republican order was already spent. Its conventions shredded. Its institutions undermined.

The civil wars that followed Caesar’s assassination were not waged between citizen rule and individual tyranny. They were waged to determine which tyrant would prevail.

Drawing these parallels is not to suggest that America is recreating Rome’s civil wars. It does not need to; it has enough civil discord of its own. And it is not to predict its decline into absolutist tyranny.

It is to reveal the stakes of what is happening in the US today.

Tom Holland once remarked in his book about the final years of the Roman republic, Rubicon, that Rome was “the first and – until recently – the only republic ever to rise to a position of world power”.

Rome was not a world power, but it was a superpower.

And it is, until now, the only precedent of a mature republican superpower that corroded from within, not at a moment of weakness, but at a time of immeasurable strength.

This is the Roman precedent that matters most for comprehending what is at stake as the Trumpist movement undermines the institutions, conventions and culture that have governed the democratic life of the American republic.

For this republic is too a prisoner of its own unresolved contradictions.

Founded as an act of democracy for a small subset of the population decrying British imperial rule, its constitutional basis encoded widespread exclusions as it defined what it meant to be a citizen.

The American republic was explicitly based upon continued slavery.

Across the centuries that followed, social struggle and political interventions gradually recast the republic to incorporate a greater degree of democracy. This was far from perfect, and the social order proved adept at adjusting to maintain the racist exclusions and forms of control.

But it is crucial that the republic was made democratic through the active mobilisation of social movements.

Recent decades have seen a conscious attempt by mobilised reactionaries to repudiate those democratic advances. This mobilisation has culminated in Trump’s politics of grievance and racial revanchism, but they did not originate there.

The institutional order is under threat. Monarch or not, the essence of what has constituted the modern American democratic republic is at risk.

At its core, a republic is an institutional order claiming its mandate from the people-as-citizens. This order is codified and given social purchase by the conventions and culture of its political life.

All this is now under threat, and as the Roman precedent demonstrates, the stakes are dire.

The greatest lesson from the Roman experiment in citizen rule is just as relevant today as ever: a Republic undone is lost forever.