Education

Getting racism out of the classroom

The storytelling in Tennant Creek is a microcosm of Australia’s struggle to come to terms with its past

Published 15 March 2022

Tennant Creek, between Alice Springs and Darwin in the Northern Territory, is about as unlike Australia as an Australian town can get, but its struggles over whether and how to tell its story have been remarkably like Australia’s.

What remains to be done in Tennant Creek suggests what Australia as a whole still needs to do as it tries once again to tell uncomfortable truths.

Tennant Creek’s story, like Australia’s, has been told in many ways: in oral, scholarly and popular histories; in official enquiries and reports; in courts and tribunals; in film, photography, music, dance, myth and yarns; and, most enduringly, by monuments, memorials and museums.

When I went back to Tennant Creek for the first time in 50 years I found that the story told by those installations and institutions of memory and commemoration wasn’t so different from the one I was taught in Grade VI social studies at Tennant Creek Primary School in 1953.

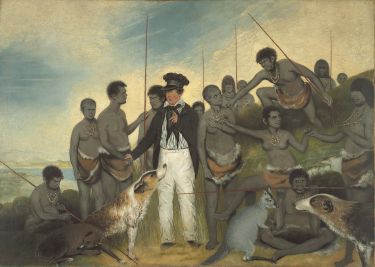

The monument to the Scottish explorer John McDouall Stuart at ‘Attack’ Creek, not far north of Tennant, marks the day in 1860 when “hostile natives” thwarted his efforts to battle his way across the continent.

Education

Getting racism out of the classroom

Not far down the road at Threeways is the towering Flynn Memorial, commemorating the Very Reverend John Flynn, the plaque declaring that “he brought lonely places a spiritual ministry and spread a mantle of safety over them by medicine, aviation and radio” – without mentioning that the mantle was for whites only.

At the old telegraph station, visitors are invited to imagine what life must have been like for those lonely linesmen of yesteryear, but not what it was like for Warumungu people when their key water source was seized and the nearby sacred site of Jurnkurrakurr defiled.

Information sheets at the old station quote from journals and official records – but not from a Land Commissioner’s report that raged against the acquisition of the precinct by the Northern Territory government “to preserve as a monument to white settlement”.

The stories told at Attack Creek, at Threeways, at the old telegraph station, and by murals, plaques and monuments in the town itself, are much the same as those told across Australia.

Of the more than 34,000 installations like these in towns and cities, in parks and reserves, beside roads and highways recorded by the estimable Monument Australia website – just 190 concern Indigenous people, places and events, and only 40 of those record violent conflict between black and white.

The storytelling of Tennant Creek’s two museums is more complicated.

One of them – the Mining Museum – celebrates the hardy pioneers of ‘the old days’, making only fleeting reference to Aboriginal people and no reference at all to their experience of miners and mining. This included complete dispossession, exploitative employment, harassment – and worse for Aboriginal women – floods of alcohol, and a failure to even think of paying royalties.

At the town’s other museum, the Nyinkka Nyunyu cultural centre, Tennant Creek’s story is told from the other side of the frontier.

It reaches across the centuries, from the days before the papulanyi (Europeans), to life “in the cattle” and at the mission, to the impact of mining, the stolen children, and struggles with the grog.

There is much more to be learned about Tennant Creek’s story at Nyinkka Nyunyu, but it’s the Mining Museum that pulls the tourists and dominates the town’s promotional efforts.

Much the same can be said of two major institutions in the national capital, the Australian War Memorial and the National Museum of Australia.

Just as the Mining Museum is almost completely silent on relations between the insurgent miners and the incumbent Aboriginal people – the War Memorial declines to tell its millions of visitors that Australia’s most consequential war dragged on for 120 years and resulted in losses far greater than Australia’s in World War II and as great (or greater) than those in World War 1.

The War Memorial has resisted frequent criticism of its silence with the argument that the story is told elsewhere, including at the nearby National Museum, as indeed it is.

But the National Museum cannot match the War Memorial’s extraordinary symbolic power.

More fundamentally, this disingenuous argument leaves the War Memorial free to tell a story of Australia’s experience of violent conflict as incomplete and misleading as the Mining Museum’s account of mining.

The infrastructure of public memory and commemoration remains a stronghold of this great Australian silence, but is difficult to change.

Much public history is official, controlled from above by those with a vested interest in myth rather than truthfulness. Mostly in the half-noticed background, it can provoke passionate attack and defence – like, for example, the much-graffitied statue of Captain Cook in Sydney’s Hyde Park.

Often in elaborate material form, it’s expensive to install and modify.

Arts & Culture

Helping us to see when we don’t want to look

Just getting rid of statues and the like is often tempting, but rarely productive. There is nothing in Tennant Creek’s public history (for example) that should be dynamited, but much that should be revised or revamped.

New plaques or information boards at Attack Creek and Threeways need to be installed to place the Stuart Monument and the Flynn Memorial in the historical context from which they arose; guide sheets at the old telegraph station need to be rewritten; the exhibition at the Mining Museum needs to be completely rethought; and new monuments and memorials to people and events currently left out of the story need to be put up in the town.

In such ways, Tennant Creek could tell as truthfully as possible what the great anthropologist WEH Stanner called “the story of relations between two racial groups within a single field of life’”.

And so too across Australia.

Dean Ashenden is a Senior Honorary Fellow at the MGSE. This article draws on his Telling Tennant’s Story: The strange career of the great Australian silence, just published by Black Inc.

Banner: Boulders of the Karlu Karlu sacred site near Tennant Creek/Getty Images