Arts & Culture

‘Like’ has totally evolved to become, like, a legit word

Love, hate or ambivalence about this vocal style may depend on our age and gender. Linguists and voice experts explain vocal fry’s origins and its place in society

Published 16 December 2020

When star of Schitt’s Creek Annie Murphy won an Emmy this year for her portrayal of beloved socialite Alexis Rose, she revealed that some of whose quirky mannerisms were inspired by reality stars like Kim Kardashian. In preparation for the role, Murphy watched clips of Keeping Up with the Kardashians and adopted Kim, Kourtney and Khloe’s use of vocal fry – the creaky voice they often do at the end of sentences that makes them sound eternally bored, cool and relaxed, depending on the listener.

If this doesn’t ring a bell, here is a short clip of Kim Kardashian’s vocal fry.

But it’s not just the Kardashians, other famous young women are renowned for vocal fry too: think Zooey Deschanel and Katy Perry. It might be that you use it yourself or you’ve never registered it or it’s like fingernails on a blackboard to you.

Arts & Culture

‘Like’ has totally evolved to become, like, a legit word

Actually, whether you grew up with blackboards or not may determine your reaction to vocal fry. It’s been around a long time, is used by males and females alike and certain tonal languages practice it more frequently.

But over the last decade, there’s been a lot of conversation about it – particularly its popularity with millennials and it’s engendering some strong opinions, mainly from people over 40.

University of Melbourne speech scientist Professor Adam Vogel says that from a physiological point of view, vocal fry is a normal behaviour.

“People have been doing it a long time. In the 1960s, researcher Harry Hollien and colleagues challenged the prevailing view of the time that vocal fry was a laryngeal pathology and was in fact a phonational register.” Dr Vogel explains that there are three phonational registers: “We’ve got the head voice or falsetto. We’ve got the normal voice and then there’s the chest register and that’s where vocal fry sits.”

“All it is really, is the slowing of the vocal folds to the point that they’re closing a lot more and they’re thicker because the muscles are contracting and taking on more mass. The more mass you have, the deeper the sound made,” says Dr Vogel.

Arts & Culture

I don’t think that word means what you think it means

“If it’s something that’s there all the time, it’s worth further investigation. But if you just do it intermittently and it’s part of your normal conversation, there’s absolutely nothing to be concerned about.” So if we don’t need to pathologise vocal fry – there’s nothing physically wrong with you if you use it –why do people have such strong opinions on it, particularly when used by young women?

A 2014 study found that vocal fry may undermine the success of young women in the labour market.

Researchers asked 800 participants to listen to voice samples of young men and women saying the phrase: “Thank you for considering me for this opportunity” in both normal register and in vocal fry and then rate which of the speakers they found more educated, competent, trustworthy, attractive and appealing as a job candidate. Listeners preferred the normal register for both male and female speakers, finding the vocal fry samples less trustworthy.

But the young women were viewed more negatively for the use of vocal fry and the researchers theorised that this was because people prefer voices that are at the average pitch for the speaker’s gender. That is, we like women to speak with higher voices and men to speak with deeper voices.

US public radio program This American Life covered the issue in a segment called ‘Freedom Fries’ in 2015.

Health & Medicine

The language of colour, kinship and climate

Male host Ira Glass discussed the vitriolic feedback the show received about various female presenters using vocal fry – “ … the most irritating voices in the English speaking world?” – before pointing out that he used vocal fry for years without controversy. Glass also made reference to a study by Professor Penny Eckert, a linguist from Stanford University, who found herself irritated by a radio presenter’s vocal fry.

Professor Eckert conducted a study where she played clips of a young woman journalist using vocal fry to 584 people and asked them to rate how authoritative she sounded.

Young people found her voice quite authoritative while people over 40 did not. Eckert’s conclusion? She was officially old.

Also in 2015, feminist author Naomi Wolf decried: “Young women, give up the vocal fry and reclaim your strong female voice”, arguing that this habit along with uptalk, run-on sentences and being softly spoken were ‘destructive speech patterns’ that ‘gatekeepers’ exploited to disregard them and their voice.

Wolf urged young women to seek out training to ‘strengthen’ their voices.

Dr Chloé Diskin-Holdaway, Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics at the University of Melbourne, says that young women are often linguistic innovators: “They’re always more likely to do something new with language. Say with the word ‘like’ and other linguistic innovations, they typically start doing it first and take all the heat.

Arts & Culture

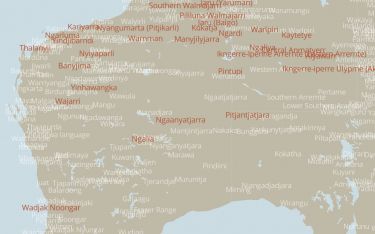

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

“Then men start to do it too and it becomes acceptable. The order with this type of language change is often young women, young men, older women and finally older men.” Dr Diskin-Holdaway says women’s language is policed more than men’s, something often experienced in respect to their appearance too. “A good analogy might be how people talk about women’s appearance and presentation. If you take a male and a female TV presenter and ask a viewer what they thought of the male’s appearance, they’re unlikely to recall much detail.

But with the woman, they might say ‘Oh yeah, she was wearing this jewellery and her hair was kind of funny and I didn’t like her top.’ Women tend to be in the spotlight more often and that translates to language as well.”

Dr Diskin-Holdaway doesn’t view vocal fry as a trend that young women consciously decide to use. She sees it more as a hallmark of millennials that distinguishes them from older generations.

“It’s different to how you choose to dress or how you choose to do your hair. You have full control over that, more or less. But it’s harder to change your accent or different qualities of your voice.

“People think that it’s some kind of affectation but in the same way that the word ‘like’ has become embedded in our grammar, vocal fry is a voice quality that can become part of someone’s style of speaking.” On the matter of people pursuing voice coaching to stop their use of vocal fry, Dr Diskin-Holdaway says “I would always encourage people to be proud of the way they speak. If they have a different accent or they speak English as a second language or have something particular about their voice, people should be accepting of difference.”

Banner: Getty Images