Arts & Culture

Is this the earliest depiction of a dodo in art?

A terrible onslaught of bubonic plague in the sixth century abruptly ended Emperor Justinian’s dream of reunifying the Roman empire and caused massive geopolitical upheaval

Published 14 August 2020

In 527 CE, when Emperor Justinian and his formidable Empress Theodora were crowned at Constantinople, the capital of the vast East Roman – or Byzantine – Empire, the sky seemed the only limit to their ambitions.

By 534, they had codified centuries of Roman civil law and jurisprudence in the famous Corpus Juris Civilis that is today still the foundation of much civil law.

December 537 saw the completion in Constantinople of the world’s largest church, the resplendent Hagia Sophia, built in less than six years.

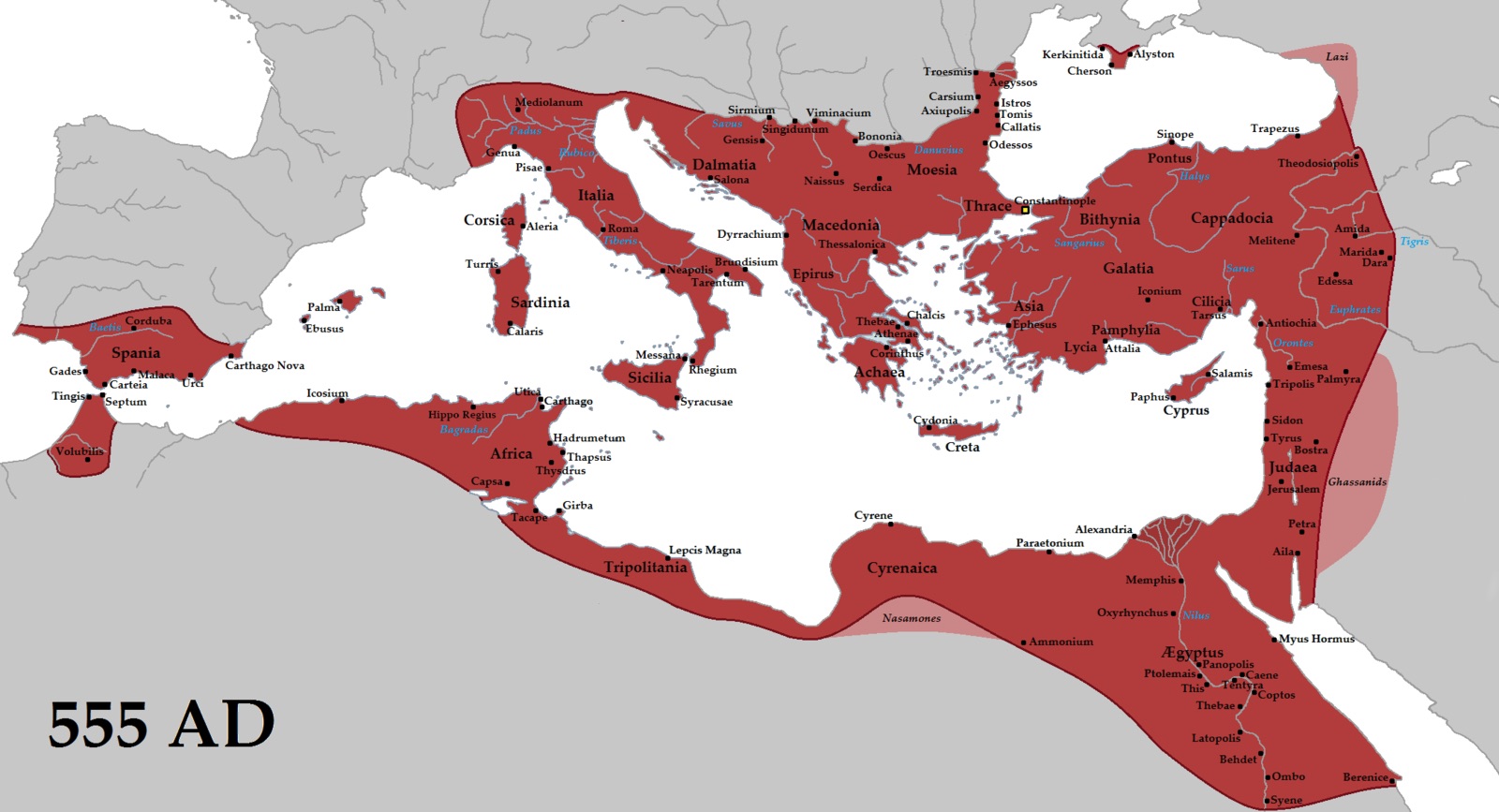

And, after buying off the rival Sasanian Persian Empire for a healthy 11,000 pounds of gold, Justinian sent his armies west where in a series of spectacular military successes they restored much of the Western empire, including Italy and North Africa, previously lost to Germanic invaders.

By 540, his armies seemed poised to even reconquer all of Spain and Gaul.

Arts & Culture

Is this the earliest depiction of a dodo in art?

But a series of natural disasters, both environmental and bacterial, would rock Justinian’s renascent Roman Empire to its very core, drowning his dreams in an ocean of misery.

It would also leave the Emperor, much like many modern leaders today during COVID-19, copping a very mixed review for his handling of a sweeping pandemic.

It started with a cataclysmic volcanic eruption (probably in Iceland in 536) that caused a volcanic winter across much of Eurasia. According to the Byzantine historian Procopius (c. 500-570), who lived through it, the darkness lasted for some eighteen months.

This triggered the coldest decade on record going back two thousand years, causing crop failures from Ireland all the way to China.

It also provided perfect conditions for the spread of a devastating outbreak of bubonic plague

Believed to have originated in China and passed through India, the so-called ‘Plague of Justinian’ arrived in Constantinople in 542 through grain ships from Egypt before engulfing the rest of the Mediterranean, Europe and the Persian Empire.

By 549, this killer pandemic had destroyed at least a quarter of the population of the Byzantine Empire – perhaps as many as 10 million people.

In Book 2.22 of his History of the (Justinian) Wars, Procopius vividly recounts the origin, symptoms, spread and reaction to the plague, which he mostly attributes to God’s displeasure with what he viewed as the rapacious rule of Justinian.

Arts & Culture

Hagia Sophia reigns serene

Procopius describes how nobody was spared and no land was spared.

The plague attacked “some in the summer season, others in the winter, and still others at the other times of the year”.

It also revisited previously afflicted places “until it had given up its just and proper tale of dead, so as to correspond exactly to the number destroyed at the earlier time among those who dwelt round about it.”

“The fever”, Procopius goes on to relate, “was of such a languid sort from its commencement (…) that neither to the sick themselves nor to a physician who touched them would it afford any suspicion of danger.”

The infected eventually developed more debilitating symptoms, ranging from deep coma to vomiting blood and violent delirium, causing no less hardship to those brave enough to care for them.

So many died that even “some of the notable men of the city (…) remained unburied for many days”. Mass graves overflowed, many towers of the city’s fortifications were filled in with corpses, or the dead were simply flung into the nearby sea.

In the face of the disaster there were spontaneous outbursts of unprecedented solidarity and compassion.

As Procopius relates, “those of the population who had formerly been members of the factions laid aside their mutual enmity and in common they attended to the burial rites of the dead, and they carried with their own hands the bodies of those who were no connections of theirs and buried them.”

Others, however, who had rediscovered religious piety in times of distress shook off their newfound devotion as soon as the plague had passed.

Significantly, Constantinople’s formidable economy abruptly ground to a halt.

According to Procopius “work of every description ceased, and all the trades were abandoned by the artisans, and all other work as well (…) indeed, in a city which was simply abounding in all good things, starvation almost absolute was running riot.”

Procopius’ claim that “the whole human race came near to being annihilated” is echoed in the Ecclesiastical History, written in Syriac by John of Ephesus (c. 507-588), another eyewitness, who claims that over 300,000 dead were taken off the streets of Constantinople alone.

He also describes how the people of Constantinople knew of the plague at least one year before it reached their city but failed to make any preparations beyond resorting to charity and other displays of religious zeal.

He recounts how the poor perished first, which he saw as an act of divine mercy since early in the pandemic there were still people willing to give the dead a dignified burial. Finally, when the rich too died like flies, widespread looting resulted in a sort of haphazard redistribution of wealth.

Much to Procopius’ chagrin (especially in Book 23.20 of his Anecdota, also known as the Secret History), Justinian relentlessly continued to tax the survivors; not to provide for the sick and the dying but to continue his building projects, notably the churches he might have hoped would placate God’s wrath.

Arts & Culture

How Arabic is a window on the world

John of Ephesus’ verdict, however, is more favourable.

He describes how Justinian and Theodora were miserable, having few servants left, and how they spared no expense to organise mass burials in mass graves – paying those able and willing to work an exorbitant amount of money, “up to a pound of gold a day and up to 100 dinars” .

Only in 1894 would the real culprit of the plague be identified as the bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried by the fleas on rats.

All of these events, the natural disasters of the years 536-549 (two further massive eruptions would follow in 540 and 547), profoundly impacted the course of history.

Justinian’s gargantuan undertaking to restore the Western Roman Empire suffered a crippling blow. Most of Spain and all of Gaul were now decidedly off limits.

For the remainder of his long reign, his weakened armies struggled to retain a tenuous hold on what they had already won. Indeed, soon after Justinian’s death in November 565, much of Italy was forever lost, this time to the Germanic Lombards.

In the years 602-628, another mutually destructive war broke out with the Sasanian Empire, resulting in a Pyrrhic Byzantine victory and chronic instability within Persia.

By the middle of the 7th century, when Europe finally saw some modest economic recovery, both the weakened Byzantines and Sasanians were rocked by Arab invasion.

Arts & Culture

Unaipon: Behind the da Vinci comparisons

Unified by the new religion of Islam, the Arabs overran the exhausted and restive Sasanian Empire, and wrestled Syria, Egypt and all of North Africa from Byzantine control.

This marked the end of what historians call Classical Antiquity, ushering in a radically altered geopolitical situation.

The anticlimactic reign of Justinian is a cautionary tale about how humanity remains ever at the mercy of Mother Nature.

It also powerfully underscores how any genuine historical understanding of the shifting fortunes of great civilisations can only be achieved by factoring in the latest evidence from environmental and health science.

Recommended further reading: Lester K. Little, Plague and the end of antiquity: the pandemic of 541-750; William Rosen: Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe; Kyle Harper: The Fate of Rome. Climate, Disease and the End of an Empire.

Banner: A mosaic of The Virgin Mary, inside Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey. Picture: De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Image