Arts & Culture

Zanuckville: Australia’s strangest suburb?

A new book explores the many – often surprising – connections between Walt Disney and Australia, most of which have faded from modern memory

Published 25 October 2024

Like many kids born in the 1950s, Walt Disney was always present in my childhood.

The first film I saw at the cinema was the Disney live-action-adventure Toby Tyler (1960). I also watched The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1958) and Zorro (1957-1958) on TV after school on weekdays, and we never missed tuning into Disneyland (1954-1997) at teatime on Sunday evenings.

However, while we were enamoured with Walt Disney, he (almost) felt the same about us.

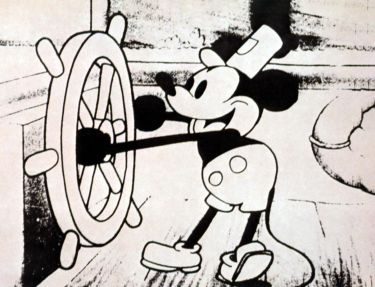

Disney’s ‘love affair’ with Australia started with a gift of a pair of wallabies in 1934. While walking past a cinema in Melbourne showing six Mickey Mouse cartoons, Leo Buring, the South Australian winemaker, had a flash of inspiration: “I thought it would be a good idea if Walt Disney made a film of the kangaroo.”

Buring promptly wrote to Disney, announcing he would present him with two wallabies on his next trip to Los Angeles in May 1934. In fact, the ship’s manifest stated that Buring was travelling with 140 hogsheads of wine, four cases of whisky and one crate of wallabies.

Photos of him presenting ‘Hoppo’ and ‘Leapo’ to Disney and a Mickey Mouse doll at the Disney Studio appeared in newspapers around the world.

Arts & Culture

Zanuckville: Australia’s strangest suburb?

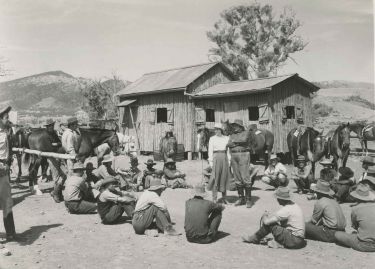

Leo Buring’s gift prompted Walt Disney to look beyond the barnyard and make an animated cartoon called Mickey’s Kangaroo in 1935, in which his famous little mouse receives a pair of boxing kangaroos in the mail.

The tag of the wooden crate containing the mother kangaroo and her joey reads: “To Mickey Mouse, Hollywood. From Leo Buring, Australia”.

This kind of onscreen acknowledgement was rare for anyone, let alone an Australian.

The success of Mickey’s Kangaroo prompted the Australian government led by Prime Minister Ben Chifley to try to persuade Disney to come here to make more films about Australia.

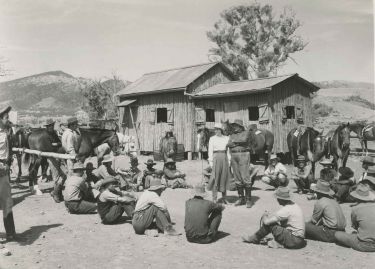

While the filmmaker never visited, despite promising several times to do so, in 1959 he sent the Academy Award-winning husband-and-wife team of documentarians Alfred and Elma Milotte to Australia to make a film about Australia’s unique wildlife called Nature’s Strangest Creatures.

Before World War II, Radio Corporation Pty Ltd was the largest manufacturer of electrical appliances in Australia, which produced valve radios too large to sit anywhere but on the living room floor.

Then, in 1933, they introduced a new compact five-valve superheterodyne or ‘superhet’ model, measuring only 10½ inches long, seven inches high, and 5½ inches wide, small enough to take from room to room and sit on a bedside table, which sold like hotcakes.

The company named its compact radios, ‘Astor Mickey Mouse’.

Arts & Culture

Homicide on Hydra

Astor Mickey Mouse radios went through several changes over the years. The 1936 model was even smaller than the original – only eight inches long, six inches high, and five inches wide – and came with a walnut-coloured Bakelite cabinet instead of a timber one.

The 1940 model had a picture of Mickey Mouse on the radio’s station clock or dial.

All this would have been perfectly fine, except Radio Corporation didn’t have Disney’s permission to call their radios ‘Mickey Mouse’.

So, better late than never, in April 1936, the company applied to the Commonwealth Registrar of Copyrights, Bernhard Wallach, to register the name ‘Mickey Mouse’ and make it official.

When Walt Disney found out what Radio Corporation was doing, he vehemently opposed their trademark application, stating that he was the proprietor of ‘Mickey Mouse’ and that calling the radios by that name would mislead the public into believing he was associated with them.

“It is immoral and unethical that [Astor] should deliberately lift words which are the invention of Disney, and around which he has built up a profitable business,” argued Disney’s lawyer Sir Robert Garran.

When Radio Corporation failed to obtain a copyright for ‘Mickey Mouse’, they appealed to the High Court of Australia to overturn it.

However, the four senior judges who heard the case – Sir John Latham, Sir George Rich, Sir Owen Dixon and Sir Edward McTiernan – once again found in favour of Disney and ordered Radio Corporation to pay costs.

The company satisfied the High Court’s ruling while thumbing its nose at Disney by renaming its compact radios, ‘Astor Mickey’.

Arts & Culture

Reframing the ‘Australian Ugliness’

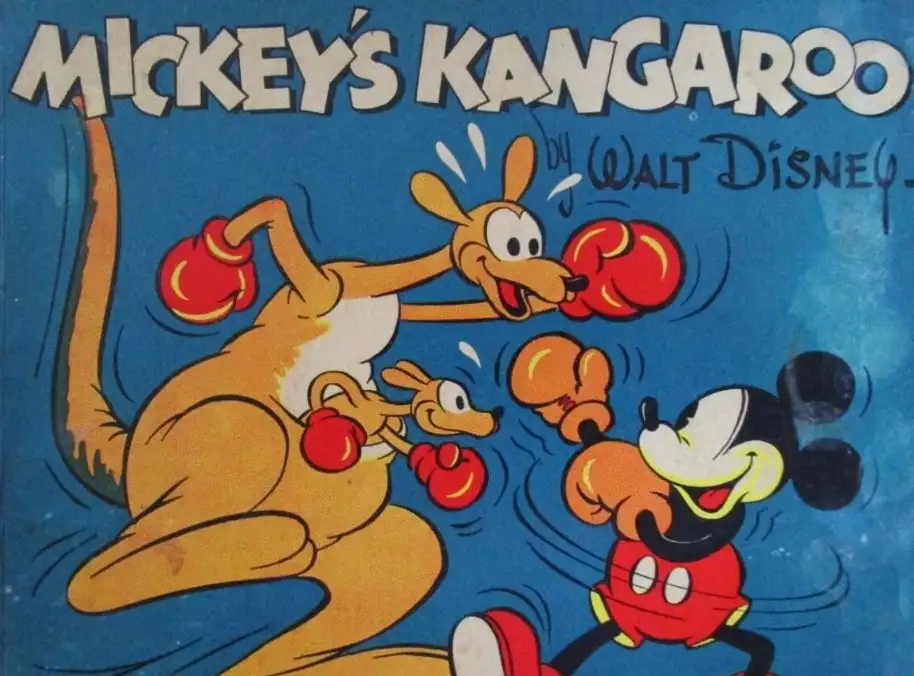

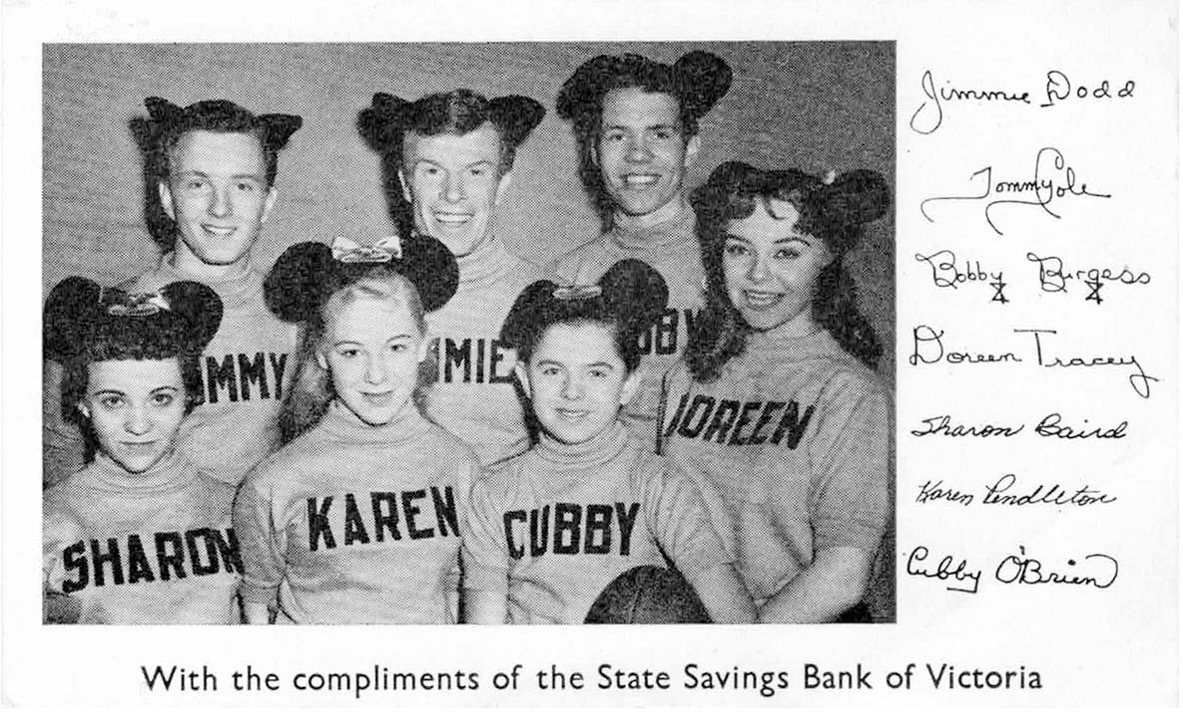

In 1959, shortly after The Mickey Mouse Club ceased production in the USA, the adult host of the hit Disney children’s TV show, Jimmie Dodd, and five of its bright young stars – Bobby Burgess, Tommy Cole, Cubby O’Brien, Karen Pendleton and Doreen Tracey – collectively known as the Mouseketeers, visited Australia to perform.

A near-capacity audience of 6,000 people attended the first of the Mouseketeers’ sixteen concerts at Festival Hall in Melbourne. Also on the programme were Diamonds, a Canadian vocal group led by Dave Somerville, along with Frank Randow and his performing dogs.

Despite the Mouseketeers’ hectic schedule, they still had time to party, especially 17-year-old Doreen, who had grown thoroughly bored with the show’s wholesome image by then.

“I’ve flipped over Dave Somerville, one of the fellers in the Diamonds,” she confessed. “He’s sweet to me. I don’t know how my boyfriend back home will take it.”

When Trevor Craddock, the marketing manager of the State Savings Bank of Victoria, which sponsored The Mickey Mouse Club on HSV-7 in Melbourne, took the Mouseketeers and the Diamonds to the Sir Colin Mackenzie Sanctuary at Healesville to see the kangaroos and koalas, “the only wildlife Doreen and Dave saw was in the back seat of the car,” he told me with a grin.

Over the years, there have also been several attempts – all spectacularly unsuccessful – to build a Disneyland theme park in Australia.

In 1960, for example, the Melbourne land development company Forest Hill Heights announced: “Victoria may get its own version of America’s famous centre of amusement Disneyland”, which would have “educational exhibits, together with the more customary forms of children’s entertainment”.

The developers decided to build the theme park in Melbourne because it had a longer dry season than Sydney.

Arts & Culture

Quiz: 100 years of Disney vs Warner Bros.

They took out an option on 500 acres of land for the Disneyland-like theme park – to be called ‘Australialand’ near Laverton in semi-rural Victoria, 17 kilometres southwest of Melbourne.

Forest Hill Heights appointed three very talented and well-qualified technical consultants to develop the new Disneyland Down Under.

There was the American Disney animator and imagineer Harper Goff, who had been responsible for developing ‘Storybook Land’, Disneyland’s beloved miniature train ride; the American Disney engineer, Jacob S. Hamel, who had designed all of Disneyland’s water features and lighting; and the English former Disney animator, John Wilson, who had recently established an animation studio in Melbourne.

When Walt Disney’s Australian representative, Walter A. Grainger, read about the plans to build a Disneyland at Laverton, he relayed the news to his boss in Hollywood, later issuing the following stern warning on Disney’s behalf:

“Walt Disney Productions and Disney Inc. of California, the originators and proprietors of ‘Disneyland’, deem it necessary, in the interest of the public and likely investors, to state that they have no connection with or interest in any proposed amusement park in Australia … Also, formal warning is given that the misuse of the name ‘Disneyland’ and the possible deception of the public may involve penalties at law.”

While Walt Disney received his ‘Hoppo’ and ‘Leapo’, Australia has still yet to get its Disneyland. Alright. So perhaps this ‘love affair’ has been a bit one-sided.

Walt Disney’s Forgotten Australia: From Mickey’s Kangaroo to Outback At Ya! (2024) by Dr Derham Groves will be released soon and is published by Palgrave Macmillan.