Politics & Society

Truth-telling and re-naming is an opportunity to redefine our future

Truth commissions in Nordic countries are addressing racism and the mistreatment of Indigenous peoples. The education sector must play an active role in truth-telling – as it must in Australia

Published 5 February 2025

It’s Sámi National Day throughout Sápmi – the Sámi homelands – which stretch across present-day Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia’s Kola Peninsula.

Sámi National Day celebrates the solidarity, strength and resilience of Europe’s only recognised Indigenous people. The date, 6 February, was chosen to commemorate the first national meeting in 1917 when hundreds of Sámi people crossed state borders to gather in Trondheim, Norway.

While Canada is an important reference point for Australia’s work addressing truth and justice, Sámi struggles for rights in the Nordic states are also instructive (though the Sámi situation in Russian Sápmi is more complex, with less legal guarantees in Russian legislative practice).

Norway, Sweden and Finland share common histories of state mistreatment of the Sámi and national minorities in Sápmi.

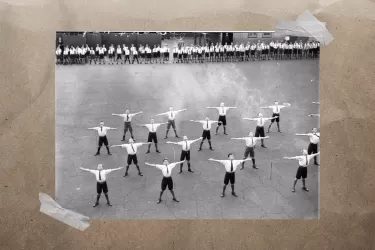

This includes assimilation policies, repression of language and Indigenous cultures and attempts to replace these with ‘modern’ western lifestyles and values.

In each case, education systems were important instruments for carrying out repressive policies and reinforcing the dominant ideas of the majority society.

As in Victoria, truth commissions have been set up to address these histories and their legacies. This work is still ongoing or only recently concluded.

Politics & Society

Truth-telling and re-naming is an opportunity to redefine our future

In Norway, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission concerning the Sámi and national minorities, the Kvens and Norwegian Finns, concluded in 2023.

The Finnish Truth and Reconciliation Commission will report in 2025.

In Sweden, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Tornedalians, Kvens and Lantalaiset (Meänkieli-speaking minority groups) concluded in 2023, while the Truth Commission for the Sámi People was established in 2021 and will report in 2025.

Here in Australia, slated changes to the Victorian curriculum and a proposed Truth and Dialogue Centre at the University of Melbourne suggest that the education sector can play a key role in the unfolding truth-telling and treaty negotiations.

But how can knowledge generated from truth-telling processes be translated across our education system? And how can university leaders, researchers and teachers work with new knowledge and enact commission recommendations?

These questions must now be negotiated here in Victoria and the Nordics in the wake of significant truth-telling processes.

Our recent comparative research investigated the relationship between truth commissions (TCs) and the education sector. We found that TCs tend to vest responsibility for redress and social change in education.

In Canada’s TC, for example, education was identified as the ‘key to reconciliation’ and wide-scale reform of curricula, policy, teacher education and teaching practice is underway.

Politics & Society

What Canada can teach us about truth-telling and justice

Here in Australia, two significant inquiry processes into historical state treatment of Indigenous people – the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1991) and National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (1997) – created a groundswell of public support for social change during the 1990s.

But, in the decades since, there has been stagnation and decline on key measures of Indigenous wellbeing and equity, and little meaningful structural reform of criminal justice or child welfare systems.

This is partly due to the ‘history wars’ – a two-decades long backlash waged by reactionaries empowered by denial of the findings at the highest levels of government.

They undermined and cast doubt on historical facts of frontier violence and child removals, arguing that truth-telling about Australia’s history was divisive and gave special treatment to Indigenous groups.

While the inquiries in the 1990s recommended major reforms of the education sector, these have been slow to happen.

My research on curriculum reforms recommended by the ‘Bringing Them Home’ inquiry found it took more than 15 years to implement those reforms.

Other systemic reforms, like the Indigenous cross curriculum priority (which mandates that Indigenous content is incorporated across all levels and subjects), and teacher professional standards (which require a demonstrated competency in teaching Indigenous students and content), have not yet fulfilled their promise to shift majority views.

This was made evident, for example, by the recent defeat of the Voice referendum and the “tsunami” of racism directed at Indigenous people during the campaign.

Likewise, the Yoorrook Justice Commission in Victoria found that cycles of systemic reforms in education have ultimately not reduced racism or improved the educational experiences of Indigenous students.

Change is clearly needed across Victorian education systems.

In the Nordics, our initial research found little to no formal requirements to teach Indigenous knowledge, as well as a lack of appropriate teaching materials and limited space in teacher education programs for Sámi-related topics.

So how might TCs, and truth-telling more broadly, offer windows of change and opportunities to rethink how new knowledge might be translated? How teacher training is organised? And how education practices could be reconfigured accordingly?

One area of potential we identified is for local institutional cultures to drive place-based reform.

For example, the University’s truth-telling project, the Truth and Dialogue Centre, and nationally significant Ngarrngga curriculum project, together, may create institutional conditions that support transformative change.

In Norway, there is a call for universities to commit to ‘gold standards’ for good work on truth and reconciliation.

Another area of focus is strengthening professional dialogue and collaboration between significant truth-telling processes and the education sector.

Research shows that it’s essential to position education as an active partner in truth-telling, and not just as an outlet for dissemination.

The education sector must also continue to look closely at its own role in colonisation and its legacies.

In the Nordics, this is not yet happening.

Sweden is embroiled in its own ‘history wars’ concerning the history and legacies of Swedish colonisation of Sápmi.

Beginning in 2018 with criticism of a report that found two out of three Sámi people experienced racism, the hostility has since escalated – culminating in the recent cancellation of a course on Sámi history at Umeå University after criticism from Sámi scholars.

Discussion & Debate

“It is a clarion call to action”

All of this is taking place against broader conservative backlash against Sámi rights in Sweden since the 2020 Girjas judgment.

This Supreme Court decision found the Girjas Sámi District retained the sole right to hunt and fish “based on possession since time immemorial”.

Like Australia’s 1992 Mabo Judgement, the Girjas decision validated Sámi land rights. But it sparked furious backlash across Sweden, particularly in Sápmi where debates over land use for mining, fishing, hunting, reindeer husbandry, forestry and Sweden’s lauded ‘green transition’ have turned hostile.

In Australia, we know too well the damaging trajectory of the ‘history wars’ which erupted out of revelations in the 1990s about Indigenous deaths in custody, stolen generations and land rights movements.

In light of that recent past, fostering opportunities for cross-national dialogue, collaboration and knowledge-sharing with the Nordics, particularly concerning education and truth-telling, have never been more vital.

‘We have always been here’, says the Sámi Parliament about Sámi people in Sápmi, echoing the refrain heard throughout this continent, ‘Always was, always will be Aboriginal land.’

This Sámi National Day presents an opportunity to reflect on the Sámi peoples’ steadfast struggle for justice and self-determination on their homelands and what that might mean for us here in Australia.

Dr Keynes would like to thank Dr Charlotta Svonni from Umeå University for providing helpful comments on this article.