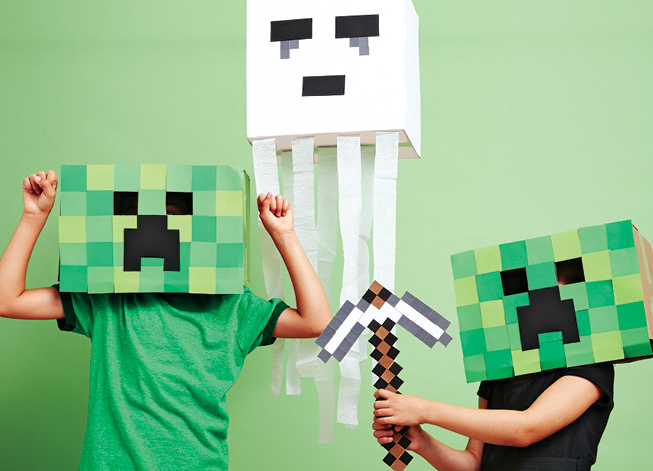

What are kids getting out of playing Minecraft?

Parents are made to worry that their children are spending too much time on their screens playing games, but maybe they’re just... playing

Published 18 February 2018

If you worry that your child has too much screen time you aren’t alone. A 2015 poll found that Australian adults rated “excessive screen time” as their top child health concern, ahead of youth suicide, family violence and bullying.

Screen time is seen by many as harmfully addictive, taking young children away from more desirable activities like reading, playing with physical toys or playing outside and getting exercise. There is little hard evidence to back up these fears, but any parent reading the Australian Department of Health and Ageing’s updated official guidelines on screen time could be forgiven for being worried.

They recommend no screen time at all for children aged under two and no more than an hour a day for children under five. Even for children as old as 12, screen time should be limited to no more than two hours a day.

So what are children actually doing when they play on their screens, and is it bad?

In fact, based on our own emerging research on children playing the popular Minecraft game, playing on screen may well be a lot like playing off screen. And no one says playing is bad for children.

Play is so strongly linked to positive social, developmental, cognitive and physical outcomes that the UN has declared the opportunity to play as a fundamental human right for children globally.

Existing research work on children’s digital play has looked primarily at the use of games in education. But, there is another strand of work, including ours, that is more concerned with children’s self-directed, leisure time play. This play, in whatever setting, is strongly associated with positive outcomes like the development of abstract thinking, self-reflection, communication skills, resilience building, empathy, and feelings of accomplishment.

Minecraft is a timely and appropriate case study of contemporary play with upwards of 120 million copies sold. According to our survey of 753 parents, almost half of children aged 3-12 play the game, mostly on tablet devices.

Working with co-researchers, Dr Marcus Carter at the University of Sydney and Associate Professor Martin Gibbs at the University of Melbourne, we found that parents associated a wide range of positives with playing Minecraft.

The most commonly mentioned of these was creativity. Parents spoke about the game ‘fostering creativity’ or ‘allowing the child to be creative’, either in a general sense, or in relation to specific game elements like design, construction, and problem solving.

Parents also noted the highly social nature of playing Minecraft. Even when children are not playing in the same ‘game world’, the verbal commentary and negotiation of in-game plans and actions provided opportunities for collaboration, negotiation, and teamwork – as well as conflict resolution.

But some parents were worried about what they thought were the excessive amounts of time children dedicated to the game. Parents in our survey talked about time on Minecraft taking away from desirable activities like non-screen based play.

Sciences & Technology

The moral dilemma: Monopoly or Zombies

But what does play actually look like in Minecraft? How does it compare with different forms of traditional play, and what are the connections and consistencies between the two? These are the kinds of questions our research is seeking to address.

Take ‘symbolic’ play for example. In a physical playground this might be something like a child using a stick as a horse or a sword as part of an imaginary story. In Minecraft, this might be a child assigning a role to an in-game object other than the role intended by the developer.

For example, in a recent Minecraft session with my three children, our avatars visited a swimming pool. I had my character jump straight into the water but was promptly informed by my five-year-old that it was of course quite silly to go swimming fully clothed. Upon further instruction I learned that the game’s diamond plated armour was to be worn as bathers, over the top of clothing mind you.

In ‘socio-dramatic’ play children enact real-life scenarios like playing ‘shops’ or ‘schools’. I’ve seen similar socio-dramatic play take place in Minecraft. My children once ran a restaurant in their Minecraft world that was supplied by a farm managed by my eldest child, who was also the town’s bus driver and the restaurant’s sole customer.

Other researchers have noted connections between digital and non-digital play. Seth Giddings in his book Gameworlds: Virtual Media and Children’s Everyday Play, gives numerous examples of children incorporating digital game features like objects, plots and game mechanics, into play that happens outside of digital spaces.

I have heard of children ‘playing Minecraft’ in school playgrounds where they substitute elements from Minecraft with readily available items like gum nuts instead of the in-game blocks of iron.

Children’s play worlds are informed by elements of both the physical, imaginary and digital worlds. For children, the boundaries between these worlds are porous and less consequential than they are for adults.

Sciences & Technology

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided unleashes potential of eye tracking

In the next phase of our research we will be documenting children’s Minecraft play in the same way that scholars have long documented traditional play. A crucial component of this process will be hearing from children themselves.

What would they like us adults to know about their Minecraft play? What sorts of play do they identify in Minecraft? What place do digital games have in their overall play worlds?

Ultimately we hope to identify possibilities for leveraging aspects of digital games to facilitate these consistencies and connections with the traditional types of play that are already highly valued. This isn’t about finding reasons to allow children unfettered access to devices. It is about looking at the reality of children playing Minecraft.

We know that parents value explicitly educational content in games, but what about play that is ‘just for fun’?

Screen based play that at first may appear a waste of time, might have more in common with the highly revered free-play of children outside ‘screens’ than we have previously given it credit for.

Banner Image: Minecraft/Microsoft Studios