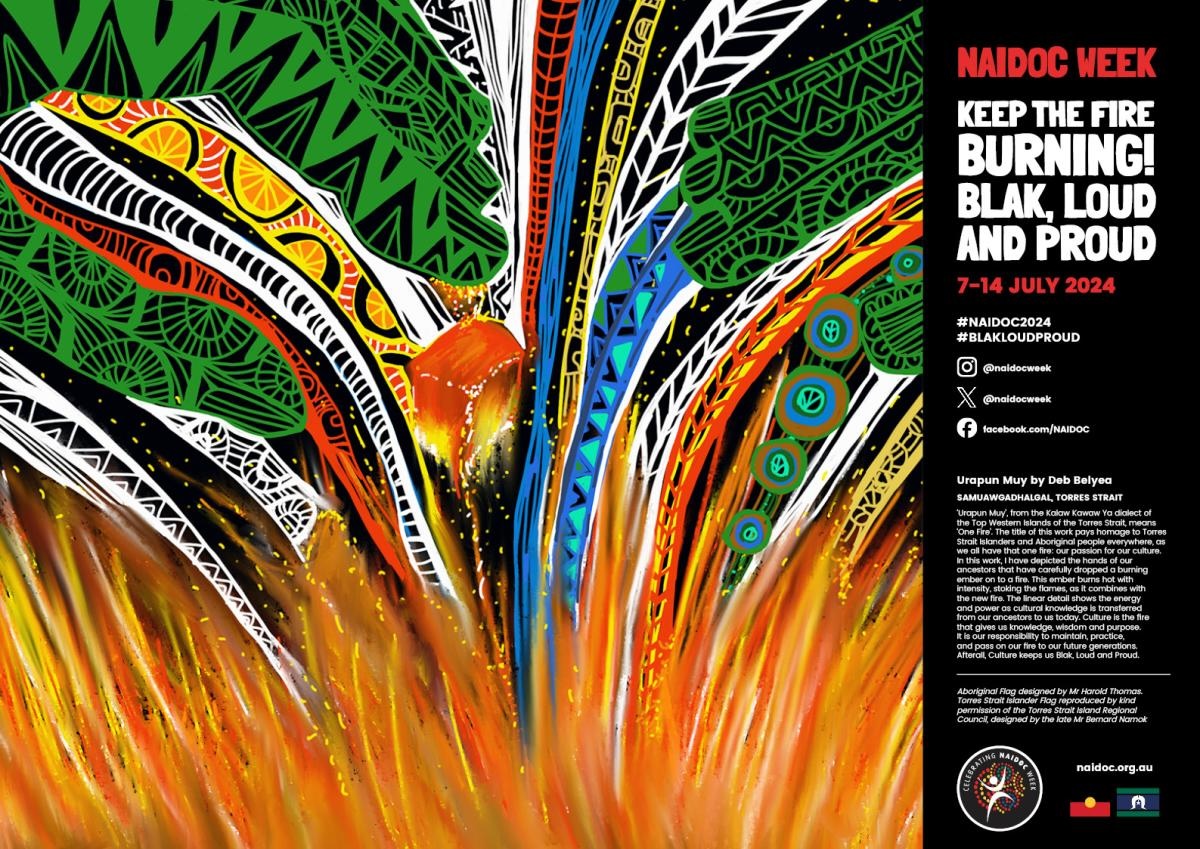

What education for Indigenous Futures could look like

As NAIDOC week celebrates the theme 'Keep the Fire Burning! Blak, Loud and Proud', the conditions are ripe for increased First Language learning across Australia’s schools

Published 12 July 2024

Through NAIDOC, Indigenous peoples build a world each year where we simply are who we are.

Being who we are is significant when modernity and coloniality have ‘othered’ us for centuries, classifying us first as non-human – on land belonging to no-one – then as part of the flora and fauna, then sub-human, and now, possibly, still lesser humans. What follows is a small canvassing of possible examples of what education for Indigenous Futures could look like.

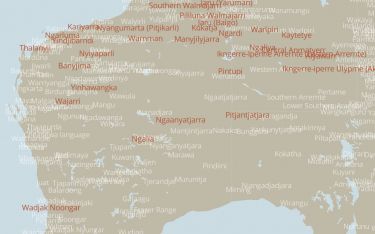

In the United Nations International Decade of Indigenous Languages; with associated federal and jurisdictional programs of policy and funding; and after decades of Indigenous advocacy and increasing Indigenous participation in formal education systems, the conditions are ripening for increased First Language learning across schooling systems.

There is the school that identifies as the first and only bilingual school of an Aboriginal language in New South Wales.

Established in 2022, the Gumbaynggirr Giingana Freedom School, based on Gumbaynggirr land in the regional city of Coffs Harbour in north coast New South Wales, realises the vision of Elders over many years and runs as an initiative of the Bularri Muurlay Nyanggan Aboriginal Corporation.

School principal Alana Jack says:

“The Western world is now trying to move back to our way, the way which is known globally as the best form of teaching and learning.

“Country is our classroom. Our new playground … and Bushtucker garden is more than just a place of play. It is an outdoor classroom. It is a place where our students will play, explore, move, and learn. It will provide many hands-on learning opportunities and ways to deepen our students’ knowledge of Gumbaynggirr language, teachings, morals, and philosophies.”

In Western Sydney, assistant principal, school teacher, children’s book author, and Dharug language teacher Jasmine Seymour is part of a small leadership group revitalising Dharug language. In fact, I am on her graduate research supervision team.

Her graduate research, ‘Nhaala, Ngarra, Banga!’ (Watch, Listen, Do), involves Aboriginal Education Officers who receive Dharug Language teacher training and who use Dharug language in their language teaching resources at the Centre of Excellence Richmond Agricultural School.

On my own Country, Wakka Wakka language in Eidsvold State School has been embedded for some years under the leadership of Principal, Preston Parter.

Mr Parter has secured Permission to Teach (PTT) for one of his key Wakka Wakka language teachers, Mr Corey Appo.

The PTT recognises Mr Appo’s Wakka Wakka cultural background, language knowledge, and Wakka Wakka language teaching skills, and was one of the first PTTs approved by the Queensland education bureaucracy.

This reads to me as an enormous innovation, being recognised as a teacher without a formal state-sanctioned teaching qualification.

We cannot talk about Education for Indigenous Futures without acknowledging the past and the present in education systems.

The National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition (NIYEC) has done hugely important work. The Coalition launched The School Exclusion Project report in March this year.

The research team found that:

“…discrimination, racism, and exclusion are foundational to Australia’s education systems and are inextricably connected to ongoing educational disadvantage and inequity … forming what they describe as an ‘elaborate technology of exclusion’ of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander young people from schools.”

NIYEC also reinforces that school exclusion is responsible for:

“…exacerbating behavioural problems, diminishing academic engagement, increased likelihood of further suspensions and exclusion, and contact with the criminal justice system.”

The old adage applies: if we do not learn from our history we are destined to repeat it.

NIYEC points to three key challenges: Access to accurate, disaggregated school exclusion data; moving away from school exclusion as a form of discipline; and looking to a form of self-determined education.

Prior to my 2024 appointment, I had been an external partner with two of the University of Melbourne's Indigenous Signature Projects.

One is the Ngarrngga Project, led by Professor Melitta Hogarth, which provides resources for Years 3 to 10, made by educators for educators along with Indigenous knowledge experts.

The vision of Ngarrngga is that “all Australian students have the opportunity to connect with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems, histories, and cultures”.

Health & Medicine

Australia needs to value Indigenous knowledge in medical education

Margo Neale and Lynne Kelly, in Thames & Hudson’s First Knowledges Series, write about the knowledge enmeshment of Sky Country with Sea Country and Land Country, practised by peoples of the Torres Strait Islands:

“Islanders use the various stars and their positions in the sky to inform them of many aspects of daily life, including the best times to plant their gardens and to hunt turtle and dugong, and to predict weather changes such as the arrival of the monsoons and changes in winds.”

In 2022, the Reading Climate research team on which I am a Chief Investigator piloted online book clubs with secondary English teachers across Australia. We centred Indigenous speculative and climate fiction.

The core research questions of our pilot study were: How do English teachers engage with Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding Country? How do they engage with Indigenous fiction in the context of climate education? And what factors prevent them from engaging with Indigenous fiction?

Of the 44 teachers in our book club pilot, 88 per cent identified as having Anglo-Australian or European cultural backgrounds.

Teachers reported a lack of confidence with knowledge of Indigenous fiction. Other findings offered insights into the kinds of approaches to teacher professional learning that might support anti-colonial, climate-aware approaches to school English.

My final anecdote comes from a serendipitous ferry ride with a friend last week.

Kat left Australia to teach English in South Korea. There, on a three-weekly cycle, each class would have an age-appropriate English language book to read and prepare an essay on.

Each term was capped off by an exam based on the same readings.

Arts & Culture

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

This left me musing. What if Indigenous-authored literature in Australian schools had such centrality? What if our pedagogies and teaching enabled such inter-cultural knowledge among students within Australia?

Could this be a way to systematically and collectively advance Education for Indigenous Futures?

This is an edited extract from the Faculty of Education Dean’s Annual NAIDOC Lecture by Professor Sandra Phillips, Associate Dean Indigenous in the Faculty of Arts 2024-2027.