What history can really teach us

History is too intricate to teach simple lessons, but knowing your history is key to understanding the complexities of the present

Published 7 June 2019

Today, at the start of the 21st century, history matters enormously to many people.

In Eastern Europe, one country after another is passing laws about what can and cannot be said about its past. Even laughing about it cannot be tolerated – Russia’s Ministry of Culture, for example, banned the 2018 comedy The Death of Stalin.

But aside from government sensitivities, history remains perennially popular. In Australia, overall enrolments in upper level history courses have increased from just over 10,000 in 1995 to well over 24,000 in 2016.

And Australia’s so-called “history wars” continuously “reignite”, whether it be competing views over British colonisation and the dominance of war in the national story, to most recently the controversy over the establishment of university courses focused on the history of western civilisation.

At my home institution, the University of Melbourne, the chair I occupy, as well as four other teaching positions in History, only exist because generous philanthropy driven by this appreciation for the past.

Why are we so concerned with history?

It is partly because history is so closely tied to identity. History can serve as the foundation of a positive sense of self, either as part of a nation, of an empire, or a civilisation.

Indeed, the role of history in shaping national identities helped to establish it as a modern discipline – it rose together with the nation state.

But the professionalisation of history has long outgrown the nationalist impulse which originally fostered it.

Academic history is so committed to the factual record and to the disciplined study of sources, that its practitioners are now often at odds with their “end users” who either want an uncomplicated story of their own heritage, or a straightforward narrative of victimisation of the group they identify with.

But there is another reason to study history – to hopefully learn from it.

In what has been mocked as a failed job application, two Harvard academics have even called for the establishment of a “White House Council of Historical Advisers.”

This group of history sages would “begin with a current choice or predicament and attempt to analyse the historical record to provide perspective, stimulate imagination, find clues about what is likely to happen, suggest possible policy interventions, and assess probable consequences.”

There is only one problem with this idea to use history to help policy makers avoid mistakes – it seldom works.

Arts & Culture

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

Historical situations are so complex, that clear parallels are rare. Historical analogies can obscure the real situation rather than elucidate it, as a major study of the phenomenon points out.

The decision to send Marines to start ground operations in Vietnam in 1965, or the intervention in Iraq in 2003 are among the disastrous choices made by historically well-read policy makers.

There are of course counter examples – American de-escalation of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 was partially driven by President John F. Kennedy remembering how World War I had started.

More recently, the memory of the Great Depression helped temper responses to the 2007-08 global financial crisis. On balance, however, the knowledge of history doesn’t guarantee good decision making.

Nor does it make you a better human being.

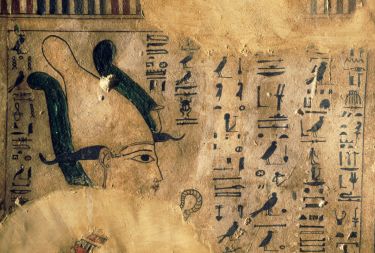

“History exists, so we can learn from it,” exclaims a 1930s bookmark signed by one Adolf Hitler.

Joseph Stalin’s library included closely annotated history volumes. The Soviet dictator was a keen student of the French Revolution, which had helped Napoleon into power.

Stalin also remembered World War I, when total war led to revolution. As a result he instituted the Great Terror of 1937-38 when nearly 700,000 people were shot in order to prevent history repeating itself.

Stalin also learned from the longer sweep of Russian history – that people needed the firm hand of a Tsar, that Russia had always been beaten because the country was weak and backward, and that weak leadership led to disaster.

He acted accordingly. Stalinism was a learned response of a diligent history student.

Arts & Culture

Rome’s Augustus and the allure of the strongman

Why then should students pursue history majors? Why should the broader public read history? There are two main reasons.

One is concern with the present – how did we get here? This approach to history doesn’t try to teach lessons from the past in order to help us make decisions by blunt analogy. Instead, it enlightens us about the legacies of what came before us. It gives us a deeper understanding of the complexities of the present.

Rather than constructing analogies between Putin’s Russia, and, say, Stalinism or the pre-Soviet Romanov empire, “applied historians” might well inform decision makers and the broader public of what historical baggage Russian, Ukrainian or Polish actors bring to the table.

Rather than constructing analogies, historians of the present might help to dismantle facile lessons from the past. They can free our minds to face challenges of the present.

The second approach to history could be called “historicist” and it insists on understanding the past on its own terms.

By immersing themselves into the traces of the past, historians can begin to understand fundamentally different ways of living. This approach can be romantic and escapist, but not necessarily.

It teaches students and history enthusiasts an analytical empathy for the past that focuses on context and reflects careful reading of primary sources – practices which are widely transferable.

History then can teach analytical and emotional abilities, and convey real knowledge about the real, contemporary world. This knowledge is gained by disciplined study of primary sources and careful interpretation of historiography.

In times of post-truth politics, these are essential skills.

Banner: Getty Images