Health & Medicine

How Australian audiologists are helping musicians with hearing loss

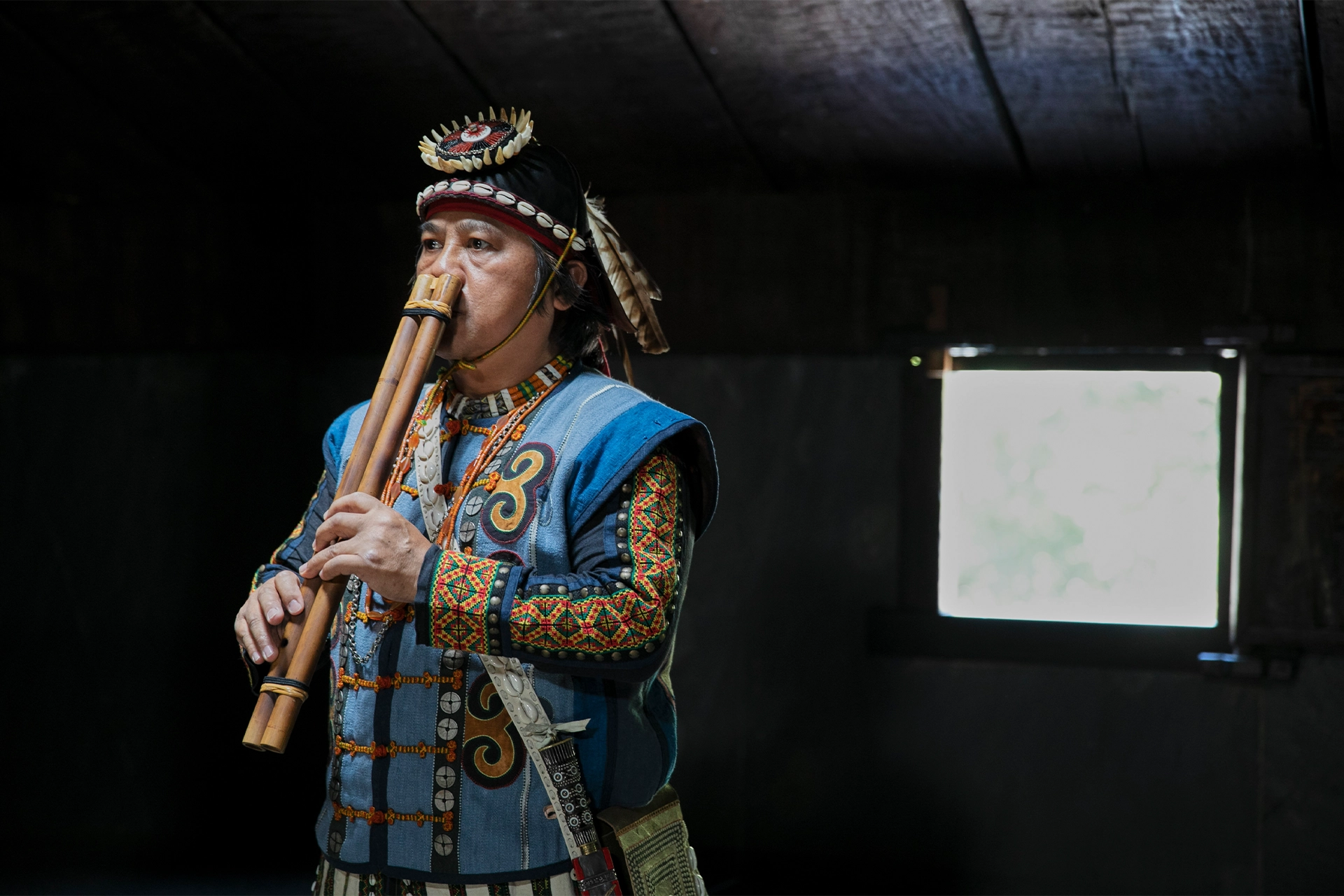

In Taiwan, Intangible Cultural Heritage – like the sound of a double-barrel nose flute – is being preserved not through recordings, but through practitioners

Published 4 October 2024

Archives are strange things. On one hand, they are repositories of the past and the people that came before us. On the other, they are partial snapshots that do not adequately capture diverse cultural practices.

The Paiwan worldview is a particularly salient example.

One of 16 recognised Indigenous tribes in Taiwan, the Paiwan people are from the Pingtung and Taitung counties in southern Taiwan.

The shape of the land and the quality of environmental sounds, like wind, are crucial to their knowledge of place, home and the past.

To rely on still photographs in an archive would limit our understanding of Paiwan and the distinctive way they communicate culture and place.

Sound is particularly crucial to Paiwan knowledge. Their music is informed by the sounds of the environment and landscape.

Consider this studio recording of Paiwan Elder Pairang Pavavalung (1935-2023) playing the double-barrel nose flute.

Composed by Pairang himself, the song ‘Itja Sa Marekaka Milimilingan' (Brothers Passing On) narrates the founding legend of Paridrayan (Dashe/Davaran) village, his hometown.

In this legend, the site of Paridrayan was recognised by sight and sound.

When in Paridrayan, two mountains – one smaller than the other – are visible on the horizon. There is a specific quality to the wind rushing across and between the mountains that is distinct.

Pairang’s flutesong is a musical translation of this windsong: he is performing what Paridrayan sounds like.

Health & Medicine

How Australian audiologists are helping musicians with hearing loss

In this audio recording, the crisp sound of Pairang’s double-barrel nose flute is a memory of Paridrayan, a place beyond our reach.

While the sound archive can document this story and host an adequate recording of the song, it cannot capture the expressive performance that keeps Paridrayan alive.

Pairang played this melody in all kinds of seemingly discordant occasions: weddings, funerals, christenings, birthdays, when serenading his wife.

The Paiwan emphasis is not only the melody per se, even though it is important, but how the song is played in different contexts.

Where and when ‘Itja Sa Marekaka Milimilingan’ is played informs the lilt, pitch, down beats, rhythm, succession of notes and so on.

A single melody can be played in a variety of ways to express different emotions – something a single studio recording cannot capture.

Paiwan flute song is not only about emotion but about the environment.

Students of the Paiwan flutes train in the wide-open conditions of the Paiwan landscape, rain or shine. They adapt their song to where they play the flutes and the prevailing weather conditions.

The flutes are played as a reflection of place: the song of Paiwan lands.

Indigenous wisdom in sound and flute is not limited to the Paiwan tribe. Other Indigenous Taiwanese people who have the nose flute include the Amis, Bunun, Tsou and Rukai.

Beyond Taiwan, we know of Māori’s Nguru, Hawaiian’s òhe hano ihu, Kalinga’s Tongali, Bontok’s kalaleng, Tonga’s fangufangu, Palau’s ngaok, and numerous others.

Arts & Culture

Building intercultural engagement through music

Many examples of these flutes can be found in museums and private collections all over the world. Some, like the kalaleng, are still in use.

However, the Paiwan flutes are special: they are the only flutes left of the double-barrel variety that remain a living tradition.

Double-barrel flutes are special because they capture breath from both nostrils. The entire body breathes out into the bamboo, making it a complete embodiment of the flautist’s purpose.

Learning to play the Paiwan flutes is a process of becoming Paiwan.

The breath is made to reflect place, which informs the specific flute song, even with the same melody.

The flautist’s body is a microcosm of the lands and context they are in.

1 / 4

The Taiwanese government recognises the significance of the Paiwan flutes, and consider the flutes as Intangible Cultural Heritage, a UNESCO term for cultural traditions or living expressions.

The late Pairang Pavavalung was acclaimed for his skill with the flutes and was named a National Treasure.

This meant that, under the Important Traditional Performing Arts and Traditional Crafts Incubation Program, managed by the Bureau of Cultural Heritage, people could register and become recognised as Cultural and Art Preservationists by training with him.

Recognition as a Preservationist is a long journey.

Trainees of the Paiwan Ravar flutes had to study with Pairang, perform a set number of performance hours and undertake regular exams by a panel of experts for at least four years.

Health & Medicine

A social media platform that is actually good for democracy?

At the point of his passing, Pairang had three students who have achieved this feat: Etan Pavavalung, Sakuliu Mananigai and Zaletj Rupunayan.

Two more were in their fourth year of study: Dremedreman Talumiling and Sutipau Tjaruzaljum. They are expected to graduate next year.

Preservationists are not immediately recognised as National Treasures. It would take an unknown number of years, nomination and agreement from the Bureau for any Preservationists to gain the title.

But Intangible Cultural Heritage recognises and attempts to capture what the traditional archive, in recordings and written documents, cannot.

When Trainees learn the flutes, they do more than just play the songs set to a fixed score. They learn to listen and hear the voice of the lands.

They learn the ancestral knowledge of Paiwan: these Preservationists are living archives.

Paiwan artists Etan Pavavalung, Sakuliu Mananigai, Zaletj Rupunayan, Dremedreman Talumiling, Sutipau Tjaruzaljum and Sedjam Mananigai will visit Naarm Melbourne in October 2024 to engage audiences with the distinct lalingedan (double-pipe nose and mouth bamboo flutes) and the pakulalu (single pipe mouth flute). Visit Art + Australia for a full list of events.