Arts & Culture

Why fake news is anything but new

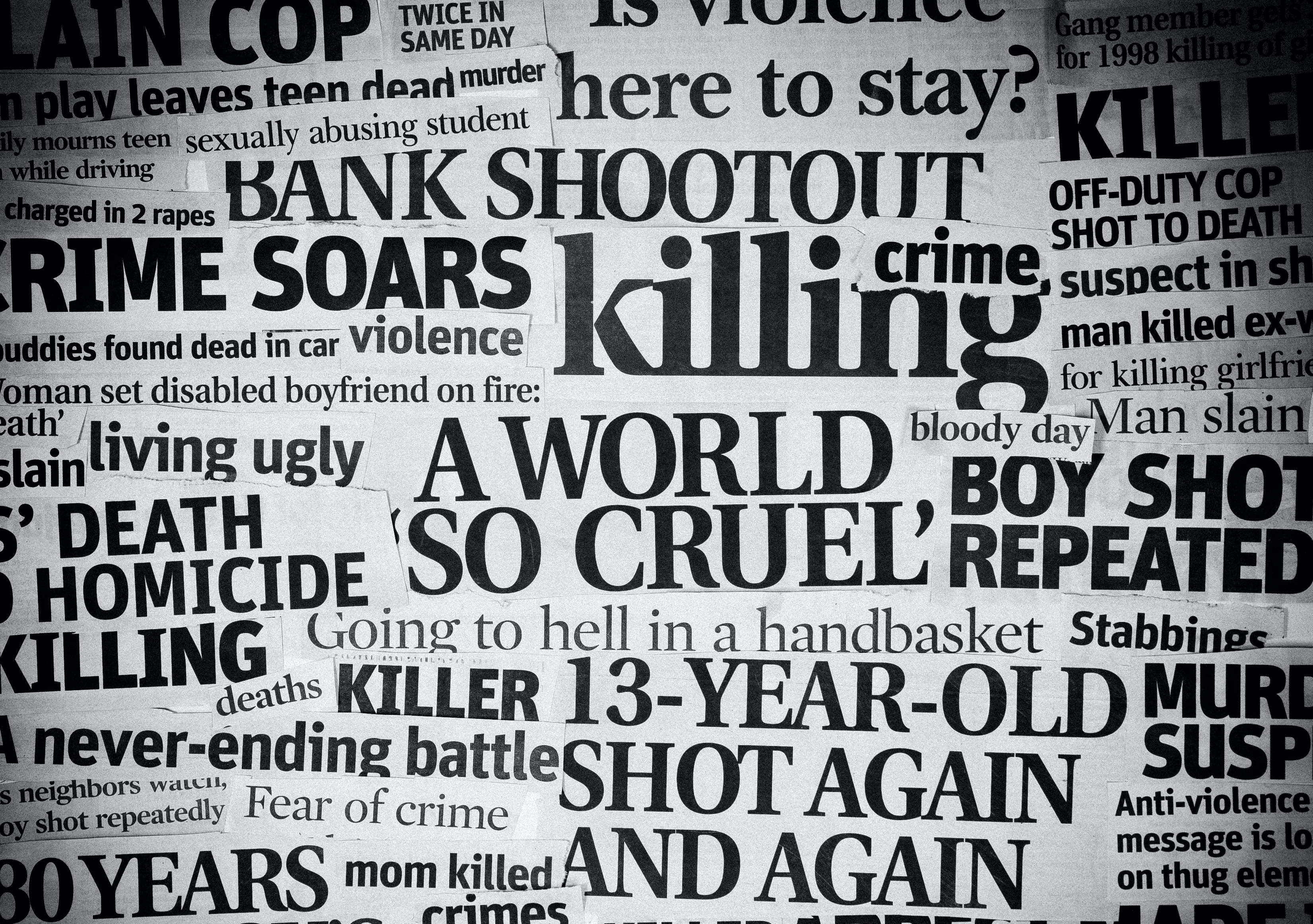

Violence, corruption and murder dominate our modern headlines, but little has changed since execution ballads were sung in sixteenth-century Europe

Published 17 July 2020

Since the start of 2020, it’s felt like the news has lurched from one catastrophic disaster to another. First came Australia’s devastating bushfires that ripped through the country, swiftly followed by a deadly global pandemic.

Most recently the headlines have been dominated by the deaths of black and Indigenous people at the hands of those in power - sparked by the brutal murder of George Floyd by a white Minnesota police officer.

The scale of news coverage and the speed with which it is consumed is constantly increasing. At any one time, we can access numerous news events from around the globe, across multiple sources.

It can be overwhelming.

But how much has the news really changed from the early days of print?

Arts & Culture

Why fake news is anything but new

Dr Una McIlvenna at the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies researches early forms of news. And although news delivery may have changed, she says, there are also remarkable consistencies within news production.

“News is constantly changing yet also keeping extraordinary continuity. The coverage of certain types of crimes remains constant.”

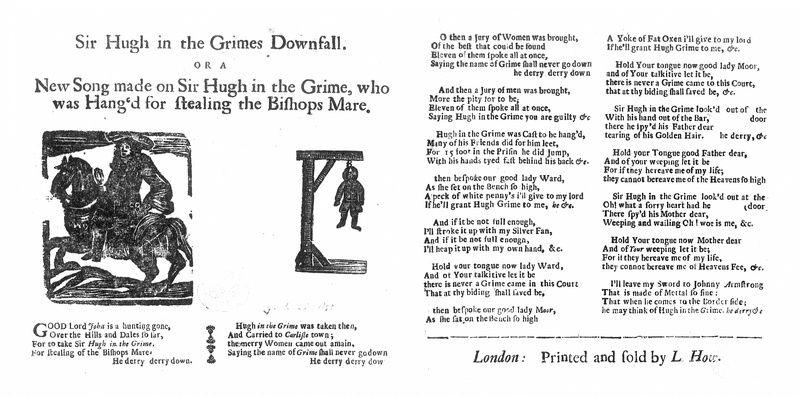

From the sixteenth century all the way through to the early twentieth century, execution ballads were one of the main forms of news.

The ballads were printed on single-sheet broadsides or small pamphlets that were sold by street sellers in Europe’s bustling streets and marketplaces. The songs were set to popular tunes known by many people and often sung by street vendors to promote their wares.

The ballads reported the crimes and punishment of those people sent to the gallows across Europe. But Dr McIlvenna says only the most gruesome crimes got reported in execution ballads.

“Murder is always the number one selling crime that gets reported.”

Execution ballads often described violent crimes in gruesome detail. And some of the language used to detail the crimes could have been lifted straight out of one of today’s tabloid papers.

Arts & Culture

A bittersweet history

This, for example, is a verse from The Yorkshire Tragedy, sung at the hanging of a murderer in York in 1685:

Now while the young Damsel lay bath’d in her blood, Which did flow from her Veins like a deluge or flood; Oh! these murderous Thieves they were pleas’d to make bold With the best of Apparel, nay, Silver and Gold, For they rifl’d the House to replenish their store, And was never discover’d for two Years and more.

“The tabloid style of sensationalism is there from the moment print begins. Every song is sold as a shocking, horrible, unheard of, terrible, ghastly thing”, says Dr McIlvenna.

And many of today’s newspaper headlines could be accused of continuing to employ the same shock tactics to hook in readers.

Today, we’re able to choose from a range of news sources. But despite the choice available to us, overwhelmingly news outlets still cover the same types of stories.

And remarkably the types of crimes covered by the news have remained consistent throughout the history of news production.

The most common capital offence that resulted in execution across Europe between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries was property crime – mostly committed by young men. However, Dr McIlvenna says it was almost unheard of for execution ballads to be written about these types of crimes.

Arts & Culture

How have plagues and pandemics influenced the arts?

“We don’t hear about those crimes in the songs; instead we get the very dramatic ones: murders, corruption… or anything done by a woman.”

And we still don’t hear a lot about the people who fill our prisons. Today in Australia there are approximately 44,000 people in jail, but the vast majority of crimes still don’t make the news.

Perhaps one of the more shocking consistencies within news reporting is its mistreatment of women.

Dr McIlvenna says misogyny has always been rife.

“There’s always been misogyny in news reporting, both victim-blaming and in the coverage of women who commit crimes.”

For example, an execution ballad from 1629 about a young woman called Alice who killed her husband in self-defence is called “A warning for all desperate women”.

And if the reader was in any doubt about the moral of the ballad, which is written in Alice’s voice, the condemned woman offers the following warning to her listeners while awaiting her fate:

Good wives and bad, example take, At this my cursed fall, And Maidens that shall husbands have, I warning am to all: Your Husbands are your Lords & heads, You ought them to obey, Grant love betwixt each man and wife, Unto the Lord I pray.

Arts & Culture

How did a cockatoo reach 13th century Sicily?

The message is clear: you should have stayed quiet; you should have done as you were told, says Dr McIlvenna.

“These are classic domestic violence cases, but that’s not how it’s told in the songs. They often mention that the husband shouted or hit them, but the message is always that the woman should have known better.”

There is no question that this type of reporting would be completely unacceptable today.

However, the news has failed to free itself of the temptation to lay blame at the feet of women for crimes committed against them. Whether it’s the clothes she was wearing, the route she took home, or the fact she chose to leave a relationship.

Too often these factors are still included in news reports and imply some sort of rationale for the perpetrator’s actions.

The fact that modern news reporting has so many commonalities with early European execution ballads is pretty remarkable, but according to Dr McIlvenna, the motivation is the same – profit.

“News has always been a business, so you always have to think who is making money out of this.”

And as long as there is money to be made out of reporting violence, corruption and murder, our modern headlines will still have much in common with sixteenth-century execution ballads.

Banner: The Idle ‘Prentice Executed at Tyburn by William Hogarth/Getty Images