Politics & Society

Is sport wandering offside?

From broadcasting to betting, players to fans – COVID-19 has permanently changed our sporting landscape here in Australia and around the world

Published 29 December 2021

When COVID-19 stopped the world as we knew it, sport became a very obvious signpost that everything had changed.

Sport was played in mostly empty arenas and stadiums, the Olympics were delayed and Australia’s two biggest football codes were left scrambling to continue.

But these changes extended beyond the pitch and into the ethos and principles of the sports industry – from racism and systemic abuse to the challenges facing fans.

We asked three University of Melbourne experts for their insights into some of the changes we saw on and off the field during 2021.

Jack Anderson is Professor and Director of Sports Law at Melbourne Law School; Professor Karen Farquharson is the Head of the School of Social and Political Sciences and Dr Jordana Silverstein is a Senior Research Fellow in the Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness (and football fan).

Politics & Society

Is sport wandering offside?

COVID-19 remained a player in the business of sport in 2021.

Sports organisations realised that they were over-reliant on three key revenue streams – ticketing, sponsorship and broadcasting.

In the search for post-pandemic alternatives, sports organisations in Australia were beguiled by private equity funding.

Private equity prompts important regulatory questions on the source of such funding, the due diligence that will have to be engaged in before accepting it, and the reasons why private equity might seek to invest in sport – ranging from commercial return to allegations of sports washing.

The more immediate impact of COVID-19 was the rescheduling of major events.

The contractual and logistical machinations behind the Tokyo Olympics were enormous, as was its budget – it was one of the costliest summer Games in history. Australia now enters a decade of hosting an array of international sporting events, culminating in its third Olympics in Brisbane in 2032.

One of the stars of the Tokyo Games was the American gymnast Simone Biles.

Politics & Society

The symbolism of the Olympic Games

The impact that convicted abuser Larry Nassar had on Biles and hundreds of others, and the resulting focus on child safeguarding, will be a sporting and legal legacy from 2021 that all of us who love sport must confront.

The second year of the COVID-19 pandemic has been challenging for Australian sport.

The sport industry has been disrupted from grassroots through to professional levels, with cancellations and delays of competitions, players playing in ‘bubbles’, many separated from family and friends, and professional matches played without spectators.

Nowhere was this more stark than at the Tokyo Olympics, held a year later than intended and without the presence of supporters.

But a key issue that has come to the fore this year has been racism in sport.

Racism in sport is multi-faceted, ranging from fans racially vilifying players, to players experiencing racism from teammates, to racialised structuring of sport opportunities that exclude non-white players from post-playing careers in sport.

Politics & Society

Racism in sport: So where to from here?

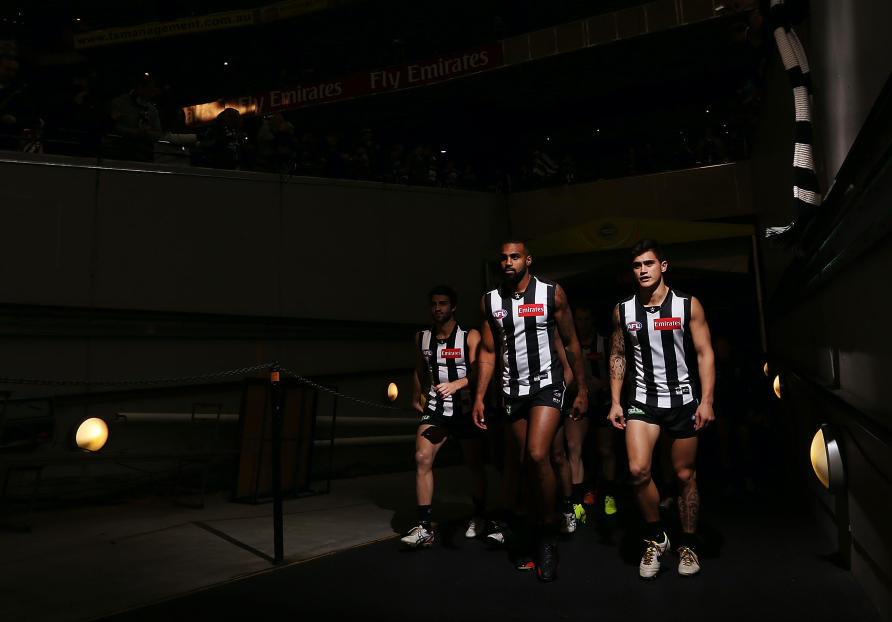

The year started with the release of the Do Better report. This report, commissioned by Collingwood Football Club, found that the club had problems with systemic racism, players and fans had experienced racism, and Collingwood’s responses to racist incidents were at best ineffective and at times actually made the situation worse.

The report made the racism at Collingwood visible in a way that it hadn’t been before, and raised the issue for other clubs and other sports. Its impact remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, acts of racism were still occurring elsewhere, including in the AFL when Adelaide Football club star Taylor Walker was found to have vilified an Indigenous player at a match.

Elite women’s basketball player Liz Cambage called out a lack of diversity in promotional photos surrounding the Tokyo Olympics, and racism in international cricket was highlighted by West Indian cricketing legend, Michael Holding, when he described his experiences of racism while playing.

This year, players came to be expected to show symbolic solidarity with the #BlackLivesMatter movement, and those who didn’t, like South African T20 player Quinton de Kock, found themselves accused of racism.

For many of us, 2021 started with attending AFL Women’s (AFLW) games.

Arts & Culture

Footy is back but times have changed

Out on the grass at Casey Fields, huddled under the shelters on a rainy Saturday at Moorabbin, or sitting with friends in the stands at Princes Park, the ability to spectate in person was back and the rush of cheering on your team was felt.

It would prove to be short lived however, and before too long those of us living under lockdown would be back to watching all sport on the TV.

But this was a year that still rewarded the sport-watcher, creating communities around the world of viewers, fans and spectators who were compelled to find new ways to enjoy their sport.

Indeed, for many people, watching sport, and the Olympics in particular, made lockdown more bearable.

During the Olympics, people had multiple screens set up to watch as much as possible. Important moments were flagged on social media, with viewers tuning in just at the right time, or grabbing opportunities to once again marvel at sports they hadn’t previously seen.

The growth of streaming meant we had immediate access to more sports, and more control over what we watched, than ever before.

Similarly the men’s AFL Grand Final became an opportunity for those who wouldn’t normally watch it, but who were sitting at home under lockdown and curfew, to participate.

Politics & Society

Footy, history and a changing Australia

In many ways then, sport watching became more widely available during 2021. It’s very different to sit at home by oneself, or with immediate family, housemates, or a bubble buddy, but spectating through social media created new ways of connecting while podcasts like The Outer Sanctum and The Final Word brought communities of fans together.

I know I’m not the only person excited about once again seeing live sport, in the flesh, without the dodgy fake crowd noises we had on television.

But I’m also glad to know that spectating sport might have become a bit more possible, and a bit more interesting, for some more people during these COVID lockdown years.

Banner: Getty Images