Sciences & Technology

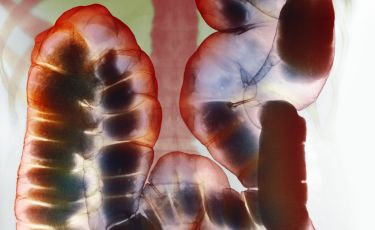

Getting to know your microbiome better

In the hunt for what's really behind non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), new research suggests an integrated approach combining dietary modification with psychological support

Published 27 March 2025

For millions of people worldwide, gluten has become a dietary villain, blamed for everything from bloating and brain fog to fatigue and depression.

These people have tested negative for coeliac disease – a severe autoimmune reaction to gluten – but at each meal, they often avoid eating pasta, bread and other baked goods.

So, what if the real culprit isn’t gluten?

New research from our team based at the University of Melbourne and KU Leuven is challenging our understanding of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) – a complex condition where people without coeliac disease report feeling better when they stop eating gluten.

We found that while people who report gluten sensitivity do experience more symptoms, these aren’t specifically triggered by gluten (the general name for a mixture of proteins found in wheat, rye and barley).

These findings raise important questions about what underlies these responses and how we diagnose and treat this condition.

Around one per cent of the population is formally diagnosed with coeliac disease, a condition where gluten triggers an autoimmune response that damages the small intestine, preventing proper nutrient absorption.

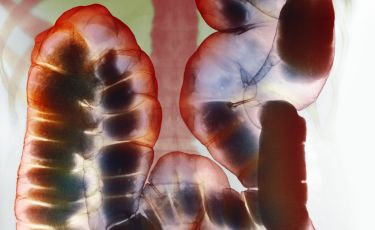

Sciences & Technology

Getting to know your microbiome better

But a much larger group – estimated at six to thirteen per cent of people – self-report symptoms after eating gluten, despite testing negative for coeliac disease.

This condition, dubbed ‘non-coeliac gluten sensitivity’, has become both a medical mystery and a marketing goldmine, with the global gluten-free product market now worth billions.

Novak Djokovic credits a gluten-free diet with improving his tennis performance and helping him reach world No. 1. Other celebrities who endorse gluten-free diets for their health benefits include Miley Cyrus, Gwyneth Paltrow and Kourtney Kardashian.

The challenge for doctors, dietitians and patients is that we still don’t have reliable tests for NCGS.

Diagnosis is based entirely on symptom improvement with a gluten-free diet, which makes it difficult to separate the physiological effects from psychological factors like expectation.

This is where a previous experience or a fear predisposes someone to expect negative effects from gluten, potentially amplifying symptoms even in the absence of a true physiological reaction.

To investigate this complex relationship, our team conducted a randomised, placebo-controlled trial with 16 people who self-identified as having NCGS and 20 healthy controls.

Sciences & Technology

Postbiotics: the new kid in the gut health family

Participants underwent both acute (single dose) and sub-acute (five-day) challenges with either gluten or a placebo mixed into yoghurt.

They weren’t told which they were receiving (single-blind trial) and researchers measured everything from mood and fatigue to abdominal pain and biological markers.

The results were revealing. People who believed they had gluten sensitivity did indeed report more symptoms, but crucially, they reported these symptoms regardless of whether they were eating gluten or the placebo.

We found that individuals with NCGS experienced more fatigue after the acute challenge than healthy controls, but this happened with both gluten and placebo.

Similarly, during the five-day challenge, they reported more bloating and abdominal pain, but again, there was no difference between gluten and placebo interventions.

Even more telling was that 56 percent of individuals with NCGS reported symptoms during the placebo phase that they incorrectly attributed to gluten. This suggests a powerful nocebo effect – the opposite of a placebo effect, where negative expectations lead to negative outcomes.

These findings align with recent landmark research showing a person’s expectation of symptoms after eating gluten has a greater impact than the gluten itself.

Health & Medicine

Taking on the ‘toxic trio’ behind coeliac disease

The study also revealed people who identify as having gluten sensitivity show distinct psychological characteristics.

We found individuals with NCGS had higher negative affect including feeling distressed, nervous and irritable, and lower positive affect scores (e.g. feeling less enthusiastic, inspired and determined) at baseline compared to healthy controls.

This doesn’t mean their symptoms aren’t real – they absolutely are – but it suggests emotional and psychological factors play an important role in how symptoms are experienced.

Interestingly, the only effect specifically attributable to gluten was on levels of tension.

After consuming gluten, both groups showed less of a reduction in tension compared to the placebo, suggesting that gluten might have subtle effects on everyone, not just those who believe they’re sensitive to it.

These findings have significant implications for understanding and treating NCGS. If symptoms aren’t specifically triggered by gluten, then simply removing it from the diet might not be the best approach for everyone.

We’re not saying people aren’t experiencing real symptoms. Our research suggests the relationship between gluten and these symptoms is much more complex than previously thought.

Sciences & Technology

From ‘honey laundering’ to fake free-range: food fraud costs billions

People with NCGS may feel better on a gluten-free diet for other reasons, including:

Reduction in other wheat components, like FODMAPs (fermentable carbohydrates) or amylase-trypsin inhibitors

Changes in overall diet quality when eliminating processed foods

Psychological benefits of taking control of one’s health

Reduction in anxiety about eating problematic foods.

Rather than immediately implementing gluten-free diets, which can be restrictive, expensive and potentially unnecessary, our results suggest a revised approach to treating people with suspected NCGS.

We need to move beyond the simple ‘gluten is bad’ narrative and move towards a more integrated approach combining dietary modification with psychological support, which may be more effective for many patients.

This might include:

Comprehensive assessment including psychological evaluation

Evidence-based dietary modifications that consider multiple potential triggers

Cognitive behavioural therapy to address food-related anxiety and nocebo effects

Gradual exposure to feared foods in a controlled, supportive environment.

Health & Medicine

How do organic and non-organic foods influence our gut microbiome?

There is growing evidence that exposure-based cognitive behavioural therapy, where patients are gradually exposed to feared stimuli like foods, can be effective in relieving both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms.

If you're experiencing persistent symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, fatigue or brain fog after eating, it's important to seek medical advice before self-diagnosing or eliminating foods from your diet.

The first step should always be to rule out coeliac disease, which requires testing while still consuming gluten. Self-diagnosing and starting a gluten-free diet without proper testing can make it difficult to get an accurate diagnosis later.

Other conditions that could cause similar symptoms include irritable bowel syndrome, food allergies or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

For those who do choose to try a gluten-free diet, working with a dietitian can help ensure adequate nutrition and a structured approach to identifying triggers.

Our relationship with food – and particularly with gluten – is complex and highly individual.

The next frontier in understanding conditions like NCGS will likely involve untangling the intricate connections between our gut, brain, expectations and the foods we eat.

And for now, that's food for thought.