Sciences & Technology

Women’s participation is crucial to fight climate change

Everyone needs access to urban green spaces, not just those in more affluent areas

Published 6 October 2023

Seeking the shade of a tree to relax or cool off is something many of us take for granted.

But as Australia heads towards an El Niño summer, the prospect of more intense heatwaves is a stark reminder that everyone needs access to urban green spaces, not just those in more affluent areas.

In the last three decades, urban green spaces (UGS) have garnered increasing attention for their significant contributions to enhancing quality of life and overall wellbeing.

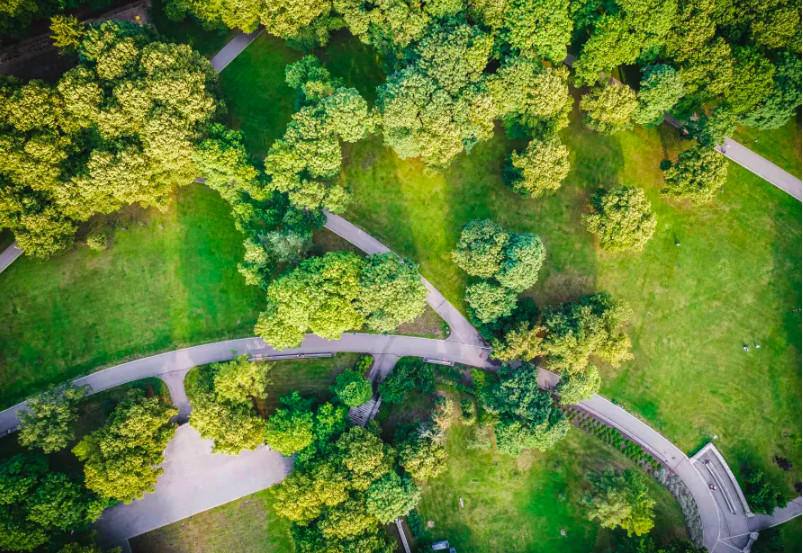

‘Green spaces’ primarily include urban vegetation, encompassing parks, gardens, yards, urban forests and urban farms – a vegetated form of open space.

Regarded as a cost-effective facet of the built environment, UGS are easily adaptable and offer a plethora of advantages: from improving air quality, reducing temperatures, providing recreational opportunities, enhancing neighbourhood livability and adding aesthetic appeal to cities.

Sciences & Technology

Women’s participation is crucial to fight climate change

Furthermore, UGS act as stress and fatigue mitigators, engendering a sense of comfort and tranquillity and profoundly impacting an individual’s state of mind. This attribute is especially vital in densely populated areas where contact with nature is limited.

Particularly during the pandemic lockdowns, UGS emerged as indispensable tools for upholding the wellbeing of individuals, playing a pivotal role in helping people navigate the pandemic-induced stressors, including elevated levels of stress, depression, and anxiety.

However, the unequal access to UGS based on socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity and age often experienced by urban residents across many global cities, perpetuates segregation patterns and worsens pre-existing health disparities.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), urban dwellers should have access to a minimum of 0.5 to 1 hectare of public green space within 300 meters of their residence. However, this is not the case in most cities.

For instance, my PhD research highlighted that only 28 per cent of neighbourhoods in Mexico City have access to a green space within 300 metres.

These neighbourhoods predominantly belong to the middle or high-income bracket, with the most impoverished areas of the city being devoid of access to green spaces.

Likewise, a study analysing the availability of green spaces in the most populous Australian cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide) revealed that low-income residents have less access to green spaces, potentially leading to increased disparities in public health outcomes.

The findings from both Australia and Mexico highlight the urgent need for affirmative action in creating green spaces to address the socioeconomic inequity in access to this vital public health resource.

In addition to ensuring sufficient access to green spaces, understanding what characteristics optimise their use and benefits for both communities and the environment is essential when planning these spaces. For instance, increased levels of physical activity are contingent on the size and features of the green space in question.

Larger green spaces with sports equipment, courts or running tracks are better suited to promote an active lifestyle. Meanwhile, smaller parks featuring gathering spaces are ideal for encouraging social cohesion.

Additionally, the vegetation in green spaces can significantly aid in cooling urban regions by combating the urban heat island effect, the phenomenon where increased urbanisation, elevated use of manmade materials, and heightened anthropogenic heat production result in significantly higher temperatures in urban areas, leading to substantial implications for the health, well-being and energy consumption of cities.

UGS benefits include mitigating the adverse health effects of heatwaves including cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, increased hospital admissions, psychological stress, aggressive behaviour and excess mortality.

In this regard, it’s important to note that not all small parks effectively mitigate rising temperatures.

Sciences & Technology

Protecting our thirsty urban trees from more harsh summers

For instance, research conducted in Shanghai, China, revealed that while pocket parks can indeed generate a mean cooling effect of approximately 1.2°C, their cooling potential is constrained by the characteristics of the surrounding landscape.

Larger parks outshine their smaller counterparts in delivering more substantial cooling benefits to the surrounding areas. Therefore, these kinds of spaces are crucially needed in the hottest neighbourhoods of cities, such as Penrith in Western Sydney, which reached 48.9°C in January 2020.

Beyond the dimensions of green spaces, different types of vegetation distinctly influence the benefits they offer. For example, increasing tree cover has proven to be more efficient in mitigating heat when compared to mixed vegetation cover or grass, as evidenced by research conducted in Sydney, Australia.

This efficiency is attributed to trees’ higher biomass density and vertical densities, providing better shading and evaporative cooling capabilities.

As a result, the impact of small, undeveloped green plots lacking trees may not be significant in producing a cooling-off effect or providing an agreeable environment to exercise during high-temperature days.

Challenges in maintaining the sustainability of green areas, especially regarding irrigation, underscore the importance of species selection and design considerations for the long-term sustainability of these areas.

Native plants are often well-suited to local conditions and can thrive in urban environments with minimal maintenance. Moreover, the interplay between pollutant concentration and tree species requires careful consideration for optimal impact.

This consideration must be made on a case-by-case basis, as it is contingent upon the geographical location and urban layout of specific areas.

Lastly, it is essential to underscore that community engagement can be a pivotal element in maximising the benefits of green spaces. Promoting active involvement of residents in maintaining green spaces cultivates a sense of ownership, pride, social cohesion and, ultimately, higher use.

For instance, programs such as the ‘Adopt a Tree’ initiative in Perth encourage residents to care for and water street trees during warm weather, generating community interest in protecting trees and green spaces, especially during warmer months.

Similarly, the ‘Adopt-a-Park’ program in Canberra actively engages the community in maintaining and enhancing green spaces, promoting long-term landscape resilience and delivering significant benefits to the Canberra community.

Furthermore, programs like ‘Friends of Parks South Australia’ strongly advocate for the protection of flora, fauna, heritage and significant sites, while also supporting a network of robust volunteer groups based in parks.

These examples underscore the significance of involving communities in the care and planning of green spaces, ensuring that the benefits are tangible and appreciated by the residents.

People’s everyday behaviours are significantly influenced by the environment in which they live, making UGS a potential tool for promoting health.

However, despite studies demonstrating that UGS can improve health outcomes, there is still a dearth of research into planning and designing these spaces to optimally enhance individuals’ health, particularly in densely populated regions.

My ongoing research focuses on identifying the ideal size and composition of green spaces to maximise their cooling effects and mitigate air pollution, particularly considering the challenges posed by rising temperatures.

Comprehending the manifold advantages offered by UGS is vital for envisioning and cultivating sustainable and inviting urban environments. These spaces can inspire healthy behaviours and happiness forging a path towards a future where cities and nature coexist harmoniously.

The journey involves addressing disparities, advancing research and adopting sustainable practices to maximise the diverse benefits that UGS can bestow upon urban environments and their inhabitants.

Banner: Regents Park, London on May Bank holiday Monday during the Lockdown, 2020