Business & Economics

Pets and Australians: Who has what?

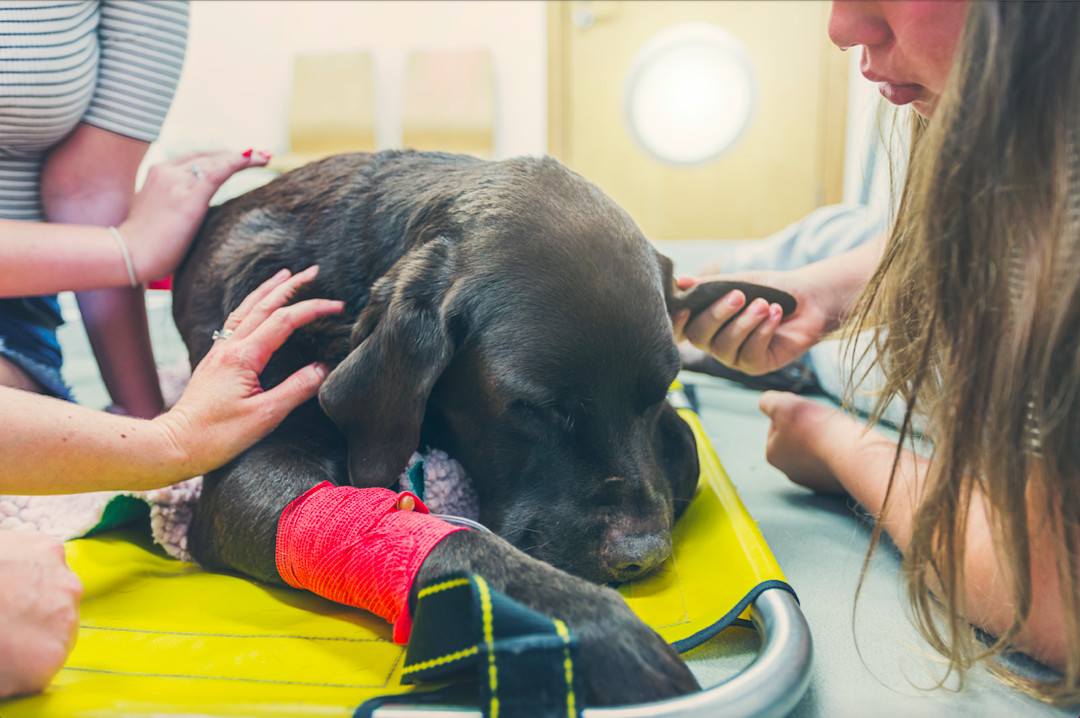

New research finds many family pets are euthanised for economic reasons, when treatment is possible, but costs are too high

Published 26 April 2021

It’s a devastating situation that too many families have had to face. Your dog is showing increasing signs of sickness – lack of appetite, energy or a change in temperament – so you bundle your furry family member into the car and head to the veterinary clinic.

Your vet examines the animal and says a biopsy or medical imaging is needed.

The tests come back, and it’s bad news. Your pet needs drugs, surgery or another procedure, which will cost thousands of dollars.

Because the tests and treatments are similar whether performed on an animal or human, so are the fees. The difference being that without government health support for animals like Medicare, you bear the cost.

Business & Economics

Pets and Australians: Who has what?

When asked if you have pet insurance, you shake your head, and the clinic has no payment plan options.

You also learn that 50 per cent of the estimated costs are required upfront before any procedure can be undertaken. So, the only other options are watching your pet’s quality of life wither as the family says a long goodbye or euthanasia.

Manuel Boller, Associate Professor (Emergency and Critical Care) at the University of Melbourne and a veterinarian at U-Vet Werribee Animal Hospital, says it’s a choice that he has seen too many families have to make, while balancing the pressures of mortgages, school fees and cost of living.

“Our pets are increasingly a central part of the family as companions to us and our children, the best personal trainers and a warm presence in the home,” he says.

“For many, losing a pet can be as hard as losing a relative. And having to make the choice to euthanise a pet for financial reasons often comes with enormous guilt.”

This issue is described as economic euthanasia, where an animal is humanely euthanised for financial reasons despite viable and available medical alternatives.

And Dr Boller says vets also suffer when faced with economic euthanasia, which for emergency vets happens several times a week.

Sciences & Technology

What are we doing to our dogs?

“Much of the medicine and equipment we use comes at the same cost as that used in human medicine; it’s often the same drugs and machines,” he says.

“Despite vets also undertaking many years’ training and gaining the experience to ensure companion animals are healthy and happy, vets are paid significantly less than medical clinicians, meaning wages are often the only area where there can be a difference in price.

“So, when an animal must be euthanised despite having a curable problem, it can be hard not to feel you have failed somehow as a vet.”

Although mental health support in the veterinary profession has become more widely available within the industry and a central focus of teaching in the University of Melbourne’s Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree, the suicide rate in veterinarians in Victoria and Western Australia is estimated to be up to four times as high as in the general adult population.

“In short, the issues of financial constraints in veterinary medical care and economic euthanasia burdens pet owners and veterinarians alike,” says Dr Boller.

As a researcher, teacher and practitioner in veterinary emergency and critical care – a high-pressure field that often encompasses difficult and high-cost treatments at all hours of the day – reducing the need for economic euthanasia has become a passion project for Dr Boller.

Sciences & Technology

Raw chicken linked to paralysis in dogs

But he discovered that the first hurdle in raising awareness of the issue was a startling lack of objective information on the extent of this problem in the scientific literature.

“It almost seemed to be somewhat of a taboo topic,” explains Dr Boller.

So, he and colleagues set out to measure the size of the problem of economic euthanasia in veterinary emergency practices. In research published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science, the team used gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV), an acute life-threatening emergency condition of dogs, as a model disease.

GDV occurs when the stomach twists or flips, often inflated by gas. The condition is readily and inexpensively diagnosed, but if GDV is left untreated, a rapid death is highly likely.

Emergency surgery leads to 80-90 per cent survival of dogs but comes with estimated costs of around $A5,000 - $A6,000 in Australian veterinary emergency hospitals.

“We hypothesised that if the owner’s decision to euthanise dogs with GDV prior to surgery was predominantly economically based, then a factor in alleviating financial strain would markedly mitigate the risk of euthanasia of these animals,” Dr Boller explains.

“We chose pet insurance as our ‘model intervention’ to reduce the economic burden on the pet owners at the time of decision making, as its presence or absence can be clearly measured.”

Sciences & Technology

Mapping Australia’s snakebites for pets

The team examined 260 cases of GDV where insurance status was known, extracting details of other health conditions, age and outcome, finding 106 deaths (41 per cent of dogs). Among the deaths, 82 dogs (77 per cent) died from euthanasia before surgery – only 10 per cent of these deaths occurred in insured animals.

In all, uninsured dogs with GDV were 7.4 times more likely to die from euthanasia than insured dogs, adjusted for age and other health factors.

“Firstly, our findings indicate that pre-surgical euthanasia of dogs with GDV is predominantly economic in nature, and second, that most deaths due to GDV occur due to euthanasia prior to surgery,” says Associate Professor Boller.

“While further advancements in veterinary care could increase the survival rates for GDV, and this should of course be pursued, the data shows the effect will likely be limited to a few percentage points. A much larger opportunity to reduce preventable deaths lays in reducing pre-surgery euthanasia, and thus in the reduction of the rate of economic euthanasia.

“It was staggering to see the size of the problem of economic euthanasia for GDV alone, but it really validates our anecdotal impression, gained from the emergency room over many years.”

He says that it is important for people to be aware that unexpected veterinary costs can be very high when considering the responsibility of owning a pet.

“Pet insurance is one way for people to feel they can pay for the treatment of unexpected veterinary medical costs and avoid economic euthanasia. Some veterinary practices also offer payment plans, which can be discussed on an individual basis.

Sciences & Technology

If we could talk to the animals

“Other tools to alleviate the burden can also include regular contributions to a dedicated savings account, low interest loans from vet-care credit companies, loans from family or friends, charity organisations or crowd sourcing.

“Economic euthanasia specifically and the financial burden of veterinary emergency care in general have been a substantial problem in veterinary medicine, and we hope that our research will help raising awareness and will stimulate the quest for effective solutions.”

If you or anyone you know needs help or support, you can contact:

Beyond Blue – Phone: 1300 22 4636 (24 hours a day, 7 days a week; Lifeline Australia - Phone: 13 11 14 (24 hours, 7 days a week); Not one more vet - provides support to all members of veterinary teams and students

Two employees of a pet insurer contributed to study design and data collection but were not involved in the data analysis or interpretation. Associate Professor Boller declares no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

The research team consisted of Associate Professor Manu Boller, Associate Professor (Emergency and Critical Care) Elise Boller, Professor (Veterinary Epidemiology) Mark Stevenson and University of Melbourne Doctor of Veterinary Medicine students Tereza Nemanic and Jarryd Anthonisz.

Banner: Shutterstock