Politics & Society

The cost to freedom in the war against COVID-19

Surveillance technology deployed to combat COVID-19 can quickly be used against civil freedoms

Published 8 June 2020

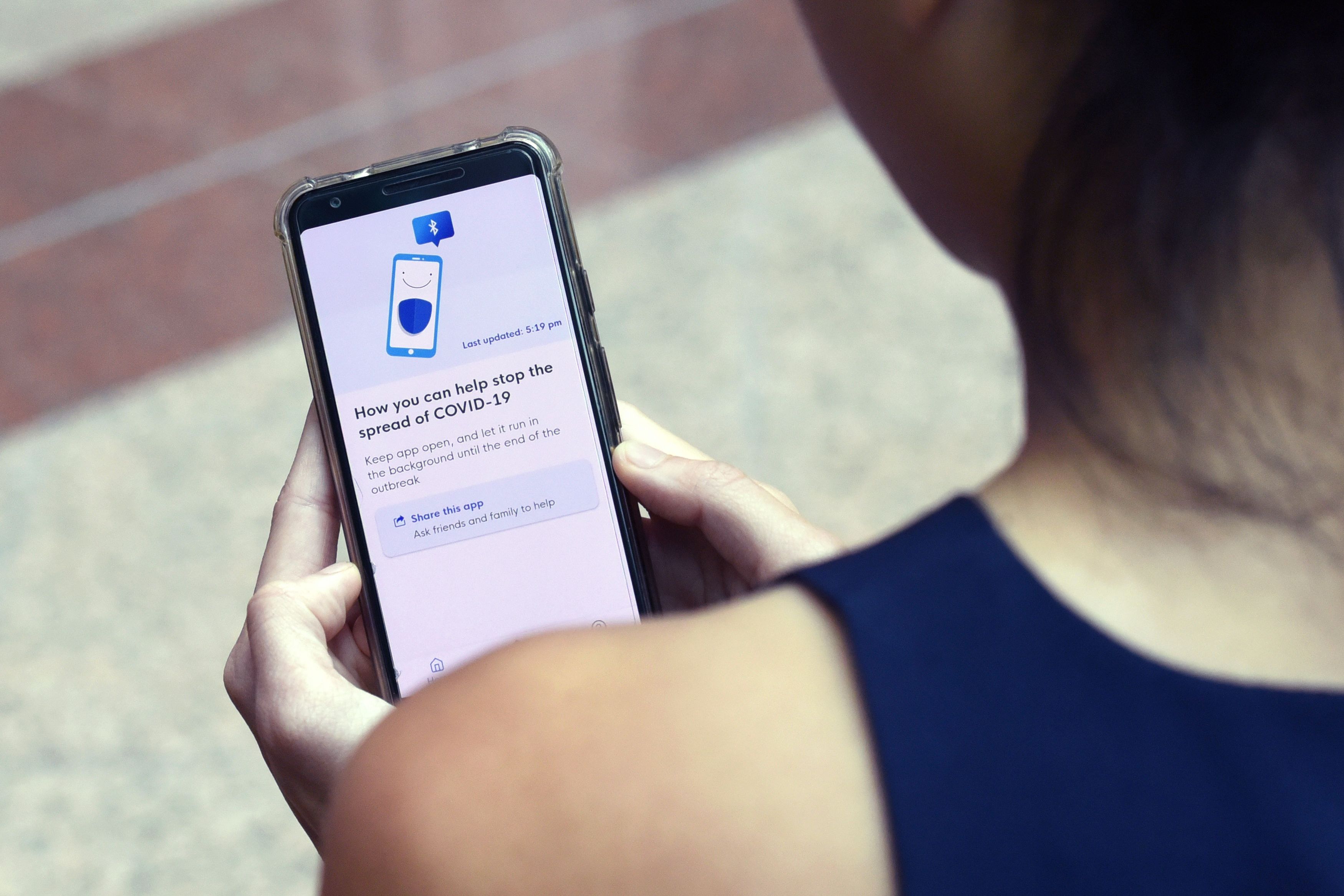

In the last few months, ‘contact tracing’, has exploded into our collective psyche.

COVID-19 has provided a need and an avenue for our governments to track us, citing our own best interests in the middle of a health crisis. But like anything, situations can change rapidly and solutions that were once deemed necessary can be used against us.

What was previously called surveillance now passes as ‘contact tracing’ for public health purposes. Yet the risks regarding the use of people’s data gathered in this way remain.

At the Centre for AI and Digital Ethics (CAIDE) we wrote in April warning that freedoms could be put at risk by the need to combat COVID-19. Our concern then was that once surveillance is implemented it can be very hard to get rid of.

Politics & Society

The cost to freedom in the war against COVID-19

Surveillance measures that were once necessary and promised as only temporary actions can quickly be redefined and redeployed for very different purposes, in the absence of strong government mechanisms that regulate and restrict surveillance.

Just over two months later, the concerns raised around the world about the dangers of surveillance have come to a head in Minnesota.

The Minnesota Public Safety Commissioner, John Harrington, made a statement that the state government would be using background checking analogous to contact tracing on people arrested during the protests that have been sparked by the death of African-American George Floyd.

His comments have stoked concerns about contact tracing and other public health measures being repurposed or their scope extended.

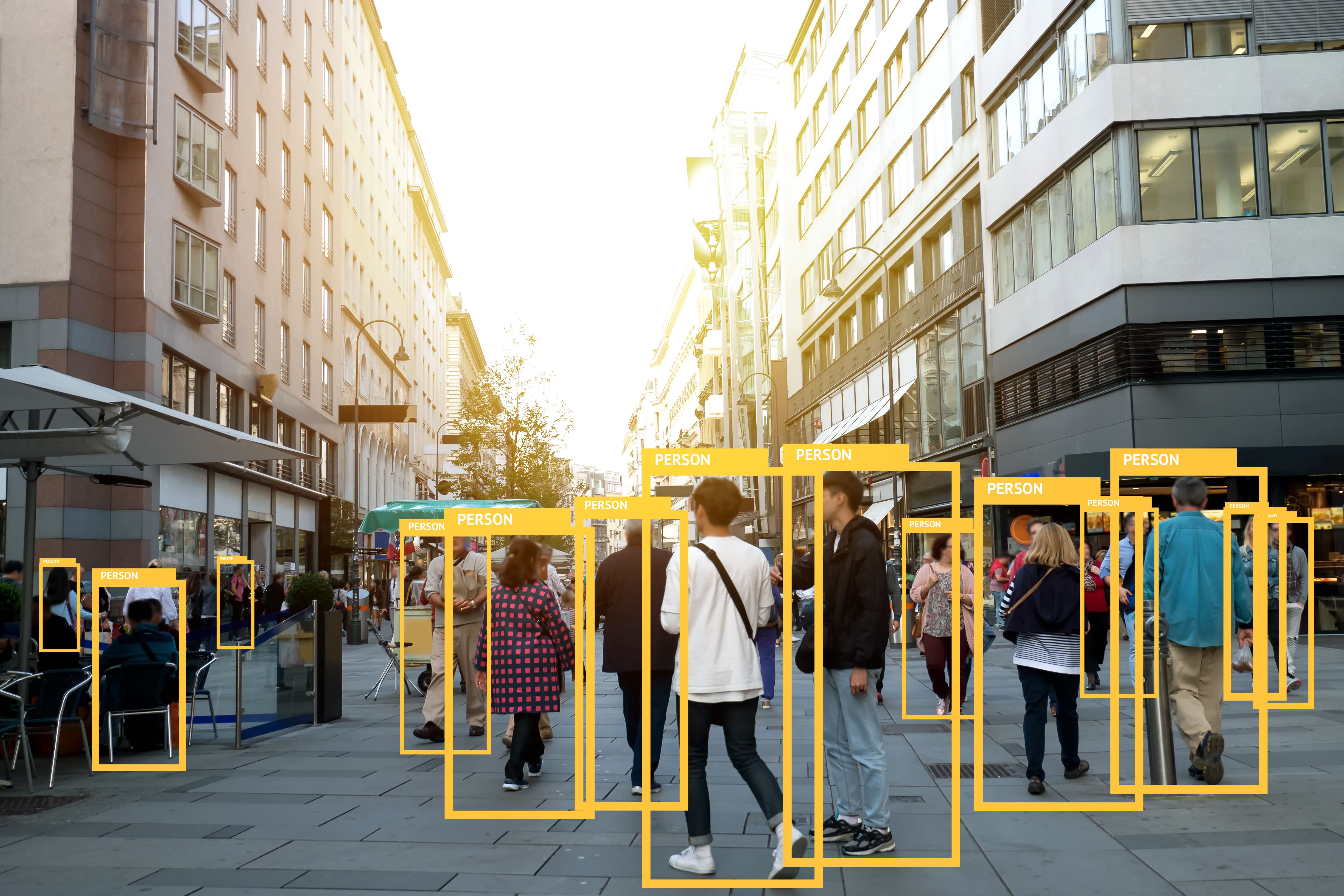

Other reports have indicated that the Minneapolis police have been trialing facial recognition technology, including Clearview AI, giving them the capacity to deploy facial recognition software on protestors.

The use of an unarmed predator drone circling above the protesters in Minneapolis only exacerbated these concerns.

While legislation should protect citizens, the unprecedented volume of data, coupled with the increased capabilities of computing to process images, voice, social media data and other data paves the way for potential misuse should security situations rapidly escalate, the way it has in the United States.

It is easy to see how COVID-19 has given rise to the next economic crisis but experts have also been predicting that COVID-19 could sow the seeds of political revolutions.

Politics & Society

The World Health Organization as pandemic police?

State of emergency laws give governments extraordinary powers.

With the development of contact tracing measures, many governments now have access to data and location information in ways they didn’t have before COVID-19. Things can change exceptionally quickly and while legislation may be in place, state of emergency laws mean that governments can bring in new legislation very quickly, allowing them to adapt – from tackling a pandemic to tackling civil unrest.

While many states of America have declared states of emergency and enacted new laws in response to protests, deploying surveillance technologies similar to those used for a public health crisis, raises even more concerns.

The US’s much touted first amendment gives people the right to protest but doesn’t include a clause exempting them from facial recognition technology.

Privacy activists across the world fear that increased surveillance capabilities will inevitably infringe on participation in political demonstrations.

Regardless of the situation that technology is being used to respond to, the surveillance techniques will be similar whether it is being used to control pandemics or control civil unrest.

The Australian government has made a huge effort to be transparent with its COVIDSafe app. But the same safeguards don’t exist for policing purposes.

In February, Vox published an article about the New York Police Department refusing to disclose details of their surveillance technology despite it being known that they are using historical data to predict future crime with AI.

Sciences & Technology

The privacy paradox: Why we let ourselves be monitored

While many liberties have been curtailed during COVID-19, all modifications to existing rights are required, under law, to be legal, necessary and proportionate. They need to come to an end.

Several researchers, including University of Melbourne’s Associate Professor Ben Rubinstein and now-independent privacy researcher, Chris Culnane, have analysed the Privacy Impact Assessment of COVIDSafe and found that authorities have the ability to decrypt the provided data and contact those who have tested positive as well as monitor their usage.

Research has also shown that further risks arise with the tracking of Bluetooth data that provides far more information than necessarily required for tracking COVID19 –in late May the Guardian reported that the app had so far identified only one case.

If governments can deploy this technology while being transparent, what is to stop governments that have no interest in transparency deploying even more invasive technology and utilising it against citizens?

While Australia has sunset clauses in place on COVIDSafe, the rate of downloads has been very low. Downloads are sitting at around 6 million, with the rate flattening after the initial hype when the app was first launched.

Research done by the Guardian has credited this to the lack of trust in government stating that it was “hardly surprising. After all, this is the same government that has deployed technology to raid reporters’ homes, harangue welfare recipients and crash the census”.

The Black Lives Matter protests in the US cut to the heart of the very issue that contact tracing creates.

When we give our data to governments, even with legislative protections, we do so in good faith. But for many citizens around the world, this requires trust in government. For many, institutionalised racism, massive income inequality, lack of legal support or protections, and violence at the hands of police, makes contact tracing measures frightening and dangerous.

Sciences & Technology

The danger of surveillance tech post COVID-19

Increased surveillance will disproportionately affect the safety and privacy of minority communities the world over.

Pandemics and other disasters call for measures that are permitted by law, and which require sunset clauses that expire when emergencies pass.

Governments have released these apps in response to extraordinary circumstances. However, consideration of privacy and the rights of all, especially minority and persecuted groups are paramount, not just in the initial disaster but because one disaster can easily perpetuate another.

The changes we make during crises need to ensure that rights are protected or they risk embedding values that may not be those that represent the society we wish to be – particularly for those most at risk of exploitation and abuse.

Banner: John Moore/Getty Images