Sciences & Technology

Paternalism, public housing and COVID-19

There are minor mistakes in Australia’s translated COVID-19 communications, but it’s more important that our multilingual communities trust in official information

Published 29 July 2020

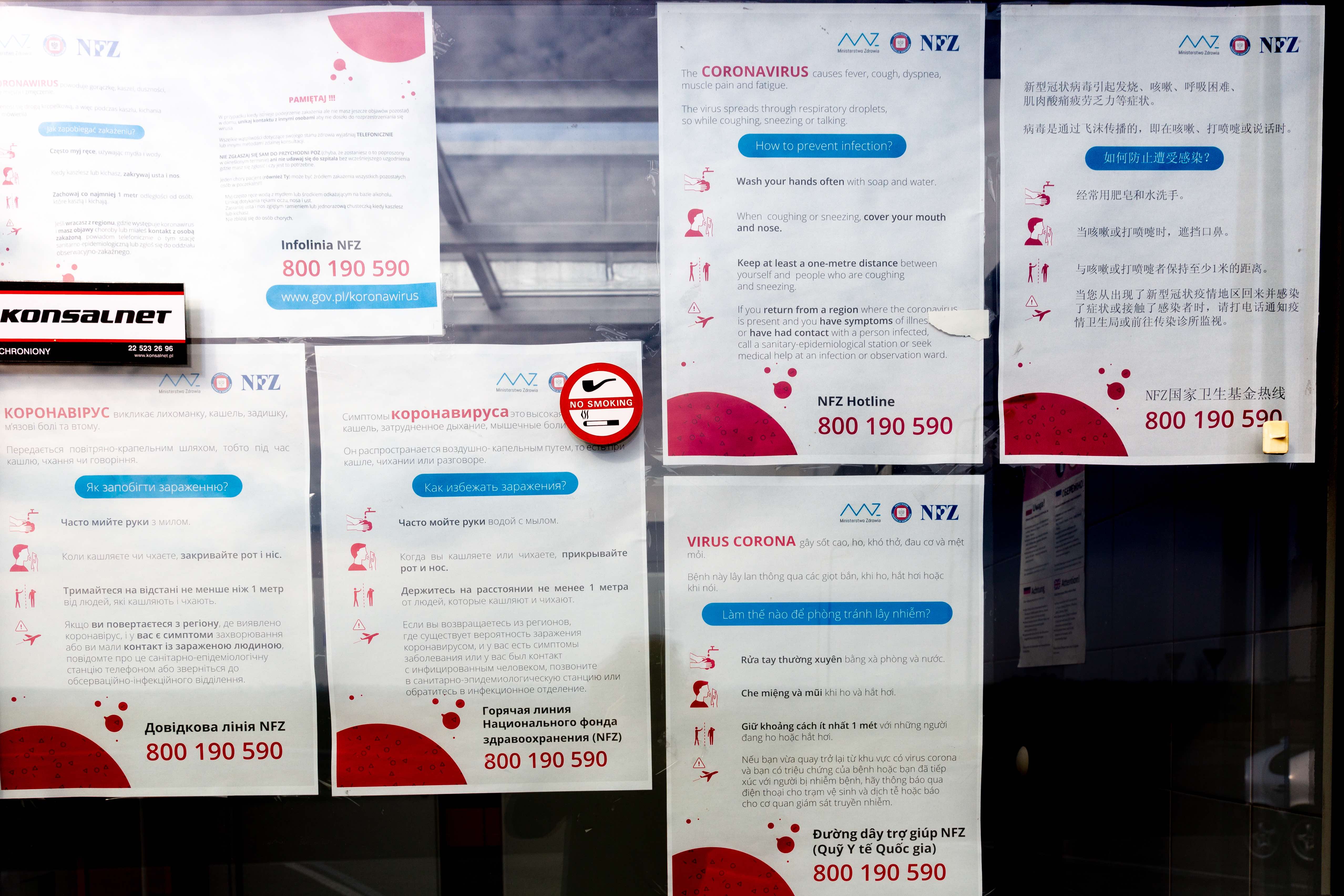

Getting vital information to Australia’s linguistically-diverse communities – like the residents of nine Melbourne public housing towers recently forced into hard lockdown – isn’t just a matter of translating well.

Australia’s translators and interpreters are certified professionals. They are tested and accredited for competence, skills, and adherence to a code of ethics and conduct.

But that code insists on neutrality and impartiality, requiring that translation professionals don’t “in the course of their interpreting or translation duties, assume other roles like offering advocacy, guidance, or advice”.

This makes sense in courts of law, where there should be no bias – but in a pandemic where people are required to change the way they live, building trust is vital if the aim is to achieve understanding and cooperation.

More than accuracy, what matters most is whether the information comes from a trusted source.

Sciences & Technology

Paternalism, public housing and COVID-19

In the current COVID-19 context, as wearing a face mask has become mandatory in Melbourne, getting these messages across clearly to vulnerable or hard-to-reach groups is more important than ever.

Our research is investigating how community groups can successfully communicate COVID-19 and pandemic health information to cultural and linguistically diverse communities.

Given that there are more than 250 languages spoken in Melbourne, this work is vital – but translating official information at this kind of scale quickly and accurately is a huge operation, and mistakes will happen.

Australia’s current COVID-19 communications, for example, contain unintentional slips.

In Burmese, the term used in pamphlets for ‘hand sanitiser’ actually refers to a substance with an alcoholic drink in it, while the term used for ‘face mask’ refers to the kind used in theatre productions to cover the whole face.

The phrase ‘outdoor gym’ disappears in Italian and Spanish translations; in Mandarin and Cantonese, it becomes something more like ‘sport hall’.

But our research isn’t focused on finding these small mistakes in official translations. It’s the community’s trust in them that matters.

Business & Economics

The economics of COVID-19

And according to previous research, in many disadvantaged or precarious language communities around the world there is widespread distrust of official information.

Anything we learn in this current context can also be applied when it comes to working out how to convey some of the more complex messages which require a change in behaviour, like those around climate change.

So, understanding this distrust is crucial.

When I was working on multilingualism and inclusion in Europe, we interviewed young refugees and asylum seekers in Leipzig in Germany and Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.

We went in with the assumption that they needed lots of well-trained interpreters, but we discovered that many viewed them with suspicion, seeing official interpreters as potential government spies. As a result, many preferred to use online translation tools to make sense of any information.

The same applied to doctors.

Many young refugees and asylum seekers didn’t trust them either – they use online translation tools before each consultation in order to prepare their knowledge of the doctor’s language, and then again afterwards, to check the advice they’d received.

Health & Medicine

What actually works for anxiety and depression?

I’ve also interviewed people who grew up under the totalitarian regimes; under apartheid in South Africa and the Assad regime in Syria.

When I asked them how they saw through the cracks in the political system, they told me that it wasn’t through reading messages from the outside, in different languages or professionally translated.

A change in awareness came from trusted individuals met in person – from knowing someone and believing what they had to say.

So, as part of our current COVID-19 research, we’re looking at the many community organisations that take official health information and make it meaningful for people, especially the elderly.

We’re trying to understand how these intermediaries can build the kind of trust that can get people to change the way they greet each other, the way they talk with each other – and to wear a mask.

What we need are people who can communicate sensitively and adapt messages to the particular needs of communities. We need people who know languages very well and can use them in very specific situations.

It’s areas like this that highlight the need to continue studying languages and humanities.

Free online translation tools can help many people communicate between languages, especially the younger generations, but if our language communities are going to understand and trust each other, we need human mediators who can build that trust.

Politics & Society

Is Australia doing enough to support the Pacific?

When I look at Melbourne at the moment, there’s a huge experiment in multilingual cultural translation going on.

Currently, there’s a lot of deep distrust between language communities, but there is also a lot of real effort being put into maintaining language and cultural diversity in an equitable and inclusive way.

The multilingual information on COVID-19 is well centralised by the Victorian Multilingual Commission and there are also great texts and videos prepared by Australia’s multicultural and multilingual broadcaster, the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS).

Both of these organisations are doing a great job, under extreme time pressure and rapidly changing information. But in-person mediators are also needed.

The solutions we find through our research can be used in multilingual cities all over the world.

Once we understand how to get these messages out to people in a way that makes them happy to cooperate and change their behaviour in a pandemic, we will know more about how to convey them to the people who need accurate and trustworthy information in the future, particularly when it comes to climate change.

Banner: Getty Images