Sciences & Technology

iVote West Australia: Who voted for you?

Victoria’s Electoral Matters Committee is looking at how our elections are conducted and internet voting is a real option. But is there any real proof that our votes would be secure?

Published 27 August 2019

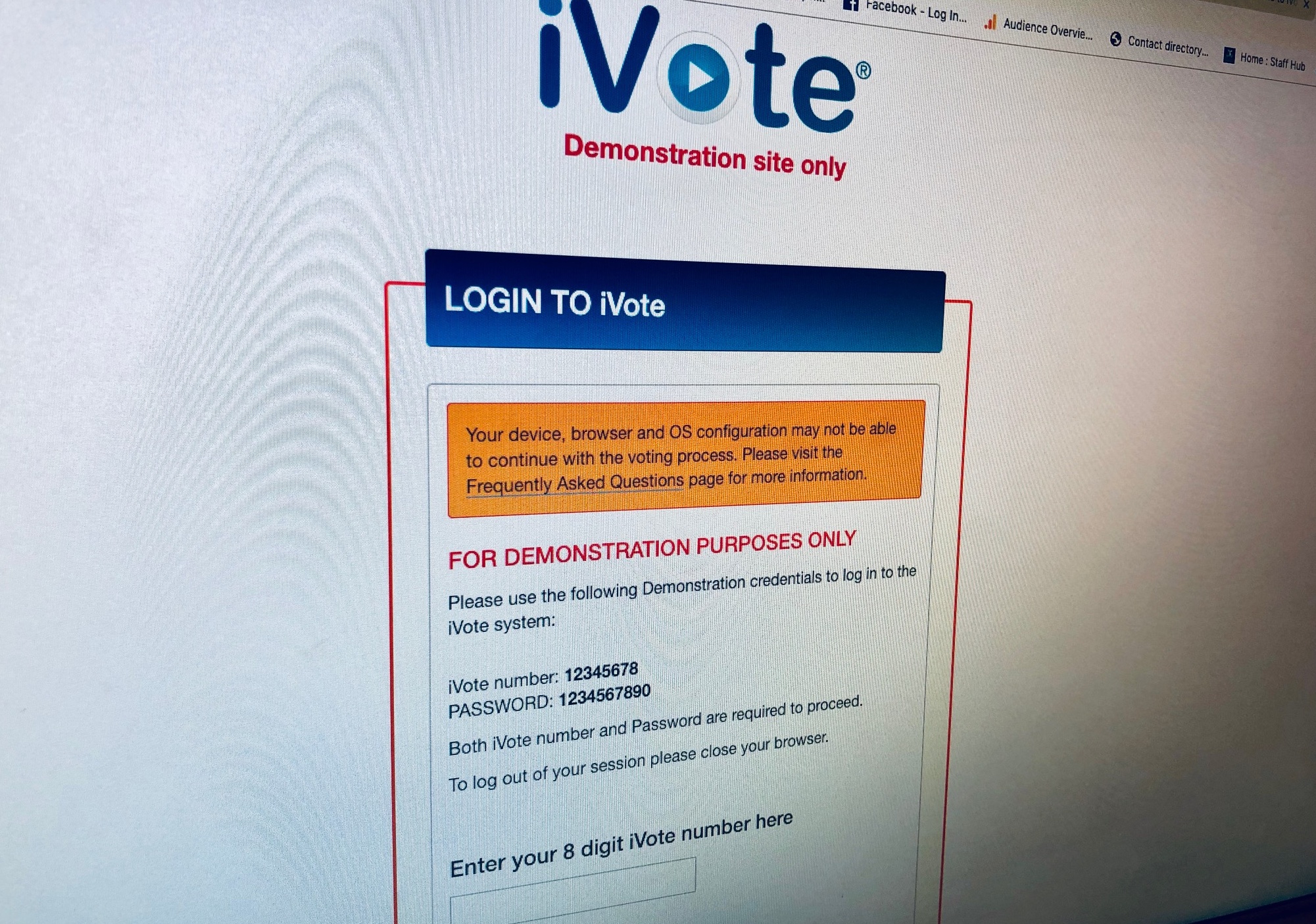

Victoria’s Electoral Commissioner, Warwick Gately AM, says that Victoria should legislate to allow Internet voting because “there is an inevitability about remote electronic voting over the internet.”

According to Mr Gately, the NSW iVote system has, “proven the feasibility of casting a secret vote safely and securely over the internet”.

The key word here is “proven”. Anyone can claim that their system is secure and protects people’s privacy, but how would we know?

Elections have special requirements. Ballot privacy is mandated by law. And elections must demonstrate that the result accurately reflects the choice of the people. So, what has iVote proven?

In 2015, our team found that the iVote site was vulnerable to an internet-based attacker who could read and manipulate votes.

Sciences & Technology

iVote West Australia: Who voted for you?

The attack wouldn’t have raised any security warnings at either the voter’s or the NSW Electoral Commission (NSWEC) end, but it should have been apparent from iVote’s telephone-based verification.

When the NSWEC claimed that “some 1.7 per cent of electors who voted using iVote® also used the verification service and none of them identified any anomalies with their vote,” we took that as reasonable evidence that the security problem hadn’t been exploited.

But it wasn’t true.

A year later it was revealed that 10 per cent of calls to the verification service hadn’t been able to retrieve any vote at all. We don’t know if this means 10 per cent of iVotes were manipulated or dropped – these verification attempts may have failed for some other reason – but we do know that the NSWEC simply didn’t tell the truth at the time of the election.

So, iVote has proven that serious errors and problems can go unnoticed or unreported.

In 2017, during a run of iVote in Western Australia, our team found that all iVotes were being funnelled through a content delivery network, which could read and alter votes.

We found servers linked to this network in North America, South America, China, and Western and Eastern Europe. This service acted as a proxy for both the registration service and the voting stage, so the voter’s identity could be easily linked to their vote.

In 2019, while examining source code of the SwissPost e-voting system that had been made publicly available for testing, we also found serious cryptographic errors that could affect the iVote system as well.

Although the system is different, both systems are supplied by the same vendor (Scytl) and have a lot of code in common.

Politics & Society

What a second flaw in Switzerland’s sVote means for NSW’s iVote

The Swiss system includes a mathematical proof that the encrypted votes have been properly shuffled and honestly decrypted. But it wasn’t sound.

Our team found several different ways in which Scytl, or anyone else with access to the server, could forge a “proof” that passed verification even though the votes had been manipulated.

NSWEC confirmed that the iVote system was affected by the problem but claimed that “the machine on which the mixnet runs is not physically connected to any other computer systems.” This isn’t relevant – we’re discussing an insider attack that forges a proof of integrity even if the system is secured from the outside.

At the time, the NSWEC said: “Our processes reduce this risk as we specifically separate the duties of people on the team and control access to the machine to reduce the potential for an insider attack. Scytl is delivering a patch which will be tested and implemented shortly to address this matter.”

So, they are saying that at the same time that they were defending against insider attacks, they were also deploying a hastily-implemented patch from a foreign provider to the core voting system, all within a few days of the election.

And wait, what was that about connectivity? That machine is “not physically connected to any other computer”. Well, neither is my mobile phone.

The heavily-redacted post-election report from the multinational consultancy PwC makes no mention of correcting the cryptography, but in issue 17 it says “[redacted] on air-gapped (offline) computers was not disabled”.

Sciences & Technology

Paper audits crucial for automated counting

We respectfully suggest that the redacted word refers to the Wireless Internet Connection, so that the supposedly air-gapped machines could actually connect to the Internet. This doesn’t prove that they were connected, only that there was nothing preventing them from connecting.

And if this machine did exfiltrate its data, it could reveal how everyone voted.

The key theme here is ‘proof’. iVote elections are not verifiable. The votes might have been manipulated or accidentally altered, or they might not, but there is no way to verify their accuracy.

This is the central problem of iVote – not only that it makes large-scale fraud possible for anyone who controls the system, but that that fraud could be completely undetectable. Even if we didn’t notice any problems, we have no idea whether the election outcome is accurate.

The concept that ‘internet voting is inevitable so stop objecting’ is wrong in both senses. It is morally reprehensible and factually incorrect.

The right to a secret ballot is enshrined in Victorian Electoral law, which permits electronic voting only in a polling place, and only if “the integrity of voting is maintained.” This would need to be rewritten to permit remote Internet voting in our elections.

Sciences & Technology

How small details can create a big problem

There are numerous alternatives to paperless Internet voting. We could extend the early voting period to give people more time to get to the polls. We could run computers in a polling place with a voter-verifiable paper record and a risk-limiting audit.

We could make candidate information available online and get voters to post or deliver a printout of their vote. We could reinvigorate Victoria’s own open-source end-to-end verifiable poll site e-voting system, vVote.

There are a lot of options, all of them far more secure than iVote.

Victoria’s Electoral Matters Committee is currently examining how our elections are conducted, and this is a process in which we can all have a say on this proposed change. You can make a submission by 30th August.

Associate Professor Vanessa Teague is the chair of the Cybersecurity and Democracy Network, an advisory board member of Verified Voting, and was a contributor to Victoria’s vVote e-voting project.

This article incorporates work and analysis by Neal McBurnett, Dr Chris Culnane, Mark Eldridge, Associate Professor Aleks Essex, Rich Garella, Professor Alex Halderman, Joe Hall, Sarah Jamie Lewis and Professor Olivier Pereira.

Banner: Getty Images