Arts & Culture

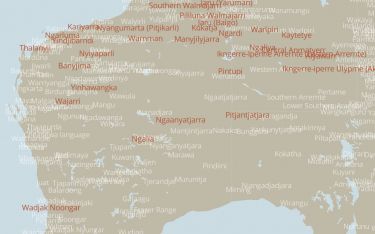

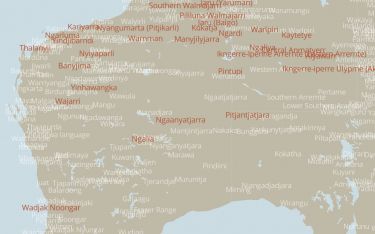

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

A new film taps into virtual reality and First Nations wisdom to help people re-conceive of the nature around them, not as a thing but as a “who” in a relationship that needs give and take

Published 4 December 2020

The urgent need for environmental action is generating new forms of human interaction with nature. Among these is a growing awareness that First Nation communities around the world have already developed sophisticated mechanisms of ‘give-and-take’ with lakes, plants, landscapes, and other natural phenomena.

I witnessed this philosophy in practice during my teenage years in Madison, Wisconsin, where a Native American Menominee community invited me into its weekly drumming ceremonies. At the time I had been inspired by my grandfather from Rio de Janeiro to explore Brazilian cultural heritage in the spiritual music of Afoxê and Candomblé.

To investigate the nexus of humanity and nature, in 2019 I visited sacred sites – guided by community elders – in Mexico, Cuba, and Australia. Their responses to my question, “what does nature mean to you?” revealed a holistic vision. For them nature isn’t a resource to be extracted, but a living entity to engage with in a relationship. At least as complex as any human being or sentient entity, nature is not a “what” but a “who.”

Returning to Melbourne in 2020 I began creating a 360-degrees interactive film to share this perspective in an immersive and engaging way. The result is the film “Who is Nature?”.

Arts & Culture

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

The film takes viewers on a journey to a Mayan sacred cenote lake and sanctuary in Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, a medicinal forest in Havana, the Afrekete Afro-Cuban festival on Australia’s Gold Coast, and the landscape of Western Australia as it is sculpted by the Aboriginal Dreamtime serpent Beemarra.

Some of the creative minds behind the project are Mexican Temazcal healer Leticia Renteria, Venezuelan ecology animator Victor Holder Rodríguez, Cuban dance educator Adrian Medina Scull, Venezuelan composer Daniel Jauregui, and Nanda elder Dr. Steven Kelly from Western Australia. Below are some thoughts from each of these innovators about the project.

Participating in this project was an opportunity to reflect and think about the ancestral cultures that still live on our planet. My interview with Adrian (the author of this article and film’s director) appears in scene two, which shows the sacred importance of cenote lakes in Mayan culture.

For me, communities that are connected with their ancestries and natural surroundings have so much to teach us about their visions of life and the universe. It would be of great benefit to our technologised Western society to open itself, listen, recognise, and adopt the truths safeguarded by Indigenous cultures.

We could all come to appreciate the profound simplicity, respect, and wisdom that encompass a leaf on a tree, a drop of water, our bodies, and every part of the universe.

Arts & Culture

Rescuing Australia’s lost literary treasures

My role in “Who is Nature?” was to work with Indigenous (Nanda) elder Dr. Steve Kelly to visually portray the Dreamtime story of Beemarra the serpent. I animated the story with a magical realism approach to show Beemarra creating the Murchison River region of Western Australia in 360 degree virtual reality.

As a Latin American with Afro and Indigenous heritage I have always been sensitive to the importance of cultural roots in building our relationship with nature. Our goal in this project is to show how we can all reconnect with the environment and with each other by seeing nature as a living organism and not as something separated from us.

In my opinion, the true cure for almost all the problems we face as human beings comes from nature. This is a perspective I have grown up with as a Cuban of African descent and I was happy to share it in the film. Many people have lost the spiritual purity to realize that plants, animals and human beings are all connected through the same channel called life.

The “Who is nature?” project stirs viewers to reflect on these connections. It is one of those projects that should be integrated into the country’s education system. I would answer the question “Who is nature?” in a very simple way: could you possibly imagine this planet without flowers?

As the musical director for “Who is Nature?” I really wanted to make the audio experience as immersive as the 360 degree film. The communities we visit in the film live and breathe nature and they know they exist within it. People in cities are more familiar with digital technology than they are with nature, but if the technology is used appropriately it can be a pathway back to our natural human roots.

Arts & Culture

Finding voice

For us, VR technology is the messenger and nature is the message. Our goal is to inspire viewers to put down their phone or VR headset after watching, and then go outside and ask themselves “Who is Nature?”

My contribution to the project was to introduce and narrate the Dreamtime story of Beemarra the serpent. The Beemarra story is steeped in Aboriginal religion and it was a pleasure to have a platform to showcase it.

Beemarra laid down laws that permitted my ancestors to survive and thrive on Country for thousands of years, and this was achieved by abiding by these sets of laws. In today’s world it is imperative that we look to Indigenous peoples’ ways of knowing, being and doing to learn how to reconfigure and adjust to our changing environment.

Within the film viewers can trigger “hotspot” buttons that open video interviews with healers and specialists, alongside maps and texts about the sacred sites.

This interactivity was achieved with help from Mitch Buzza and Sam Taylor at the University of Melbourne’s eTeaching/eLearning team. Meanwhile, Auryn Rotten and Luis Gaitán from Learning Environments stitched together the 360 degree film and produced the videos interviews. Input from Weijia Wang (digital entertainment creator) and Thomas Keep (intern at the Digital Studio) was critical in resolving these questions.

Arts & Culture

Museums in cyberspace

The film is set to an original soundtrack, composed collaboratively by Grammy Award winner Daniel Jauregui (Harmonic Whale Studio), Leonard Barker, and community arts organisation Suns of Mercury.

A highlight of the soundscape, for me, emerges at the end of the scene walking along a path at the Tsukán Sanctuary in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, when the bird songs and chirps come together in chorus with the piano and drums.

The film attempts to bring the natural and technological realms together to evoke an ancient insight: if you want to know who you are then begin by asking “Who is Nature?”

A webinar about the project for the Indigenous-Settler Relations Collaboration can be viewed here.

Banner: A cenote lake on the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Getty Images