Sciences & Technology

How convincing is a Y-chromosome profile match?

We can find out about our ancestry or our risk of disease through our unique DNA - but do you know who has a right to access and use that information?

Published 26 November 2017

When you’re clipping your nails or having a haircut, do you think about who owns those samples of your genetic material? Perhaps you think it doesn’t really matter, or that because it comes from your body, you own it.

In fact, legally, the answer is far more complex.

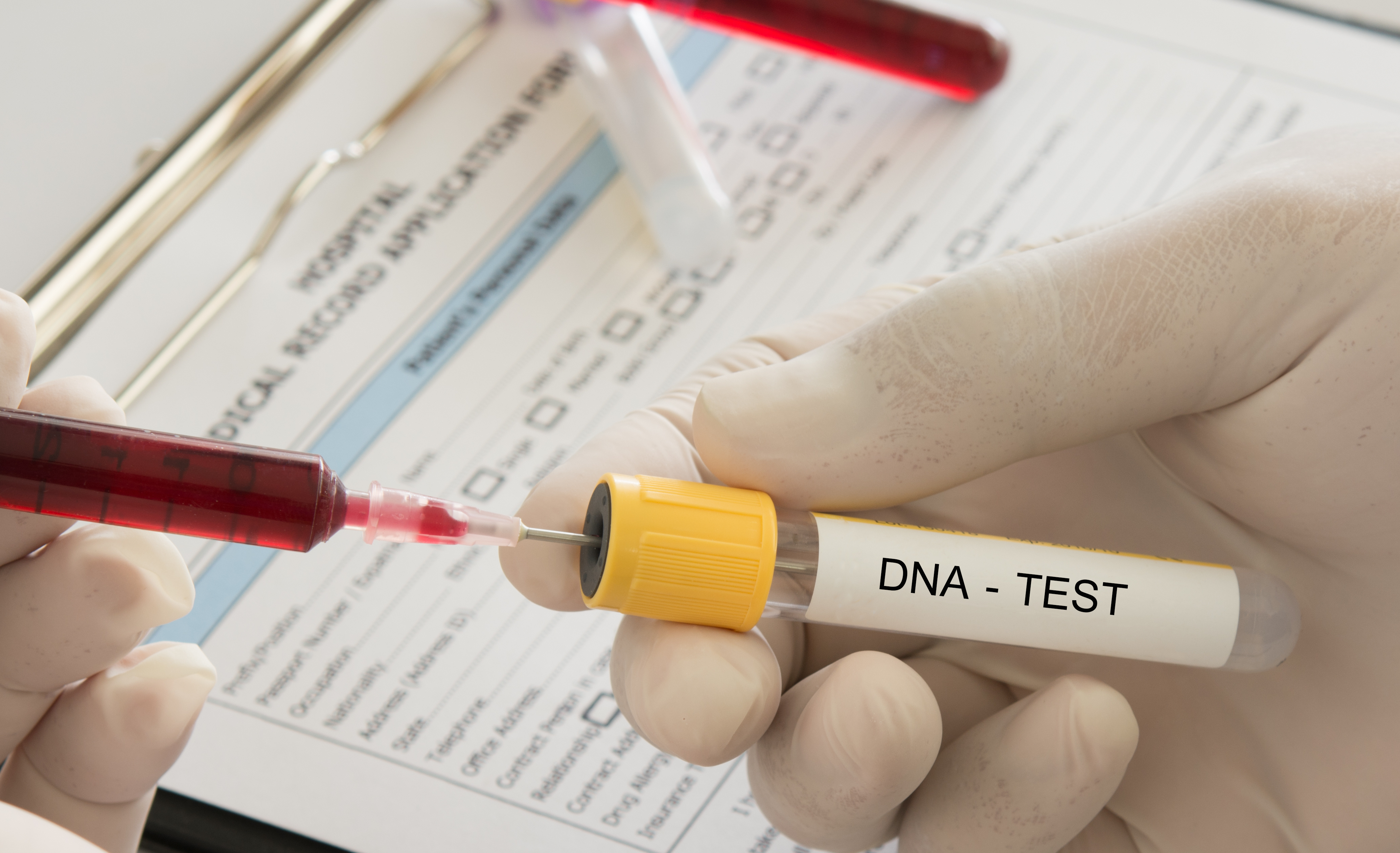

These days it’s easier than ever to find out more about our family history by sending off saliva samples to companies who can trace our family tree. Some of us may also be happy to donate samples for medical research. But do we understand the relevance of information we are giving up about ourselves, and the implications of giving others access to our unique data? And could what’s known as a Dynamic Consent model help inform us better?

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) is found in human cells and contains the genetic information that directs the body’s growth, maintenance and reproduction. Although humans share 99.9 per cent of the same DNA, it is a unique personal identifier and can tell a whole story about who we are and where we come from.

Sciences & Technology

How convincing is a Y-chromosome profile match?

It is possible to extract DNA from almost any human sample, including nails, blood, and sperm. DNA is also detectable on objects we’ve come into contact with like chewing gum or the smear we’ve left on the side of a glass.

What this means is that it is accessible and may be used by those with enough expertise and interest.

Samples of our DNA have value, both to us and to others. For example, DNA samples are used in criminal databases. Here in Australia, police use the National Criminal Investigation DNA Database (NCIDD) to inform or support investigations by linking DNA profiles from a crime scene with convicted offenders.

Some of us also happily post off saliva samples to family history companies, use direct-to-consumer genetic profiling tests, or donate samples for medical research.

But giving others access to our DNA raises questions about privacy, property and fair use of DNA. For example, how should we balance respect for individual interests and the ‘greater good’ of research?

Given we share so much of our DNA with our relatives, an argument could be made that it is ‘owned’ by family members. Genetic make-up presupposes stories and a shared history, giving rise to joint interests.

For example, a recent English case raised the question of whether the pregnant, adult daughter of a prisoner diagnosed with Huntington’s disease had a right to know about the potential risk to her because of their genetic heritage.

Here in Australia, indigenous groups subscribe to the concept of collective rather than individual ownership of genetic samples, so it is considered appropriate to obtain consent from individual participants and the local community for any genetics research conducted with these populations.

Some may think ‘ownership’ is too simplistic to fit with the concept of DNA ‘belonging’ to families or communities, and ideas of ownership may be difficult to apply in a legal and practical sense.

Health & Medicine

A chip off the DNA block

But this concept of ownership implies value. For an individual, the value of a DNA sample may simply be that it enables us to find out more about our family history or likelihood of future disease. But cumulatively, samples of DNA have great value - for research leading to development of future treatments. Genetic and genomic research requires access to human DNA from biological specimens, which can be stored and used in multiple areas of research.

Being able to use samples of tissue however is different from owning them.

Case law in Australia states that there is no ownership of the body or body parts. The reasoning is that after death a body must be buried swiftly, and this could be delayed if family members or executors owned the body. However, human bodies or parts can be the subject of property rights where work or skill has been used to transform them, for example into an exhibit.

This argument can also be applied to collections of human tissue used for research studies.

A tissue sample may become the property of a research institute if it has acquired the sample lawfully, with consent, and work or skill has been applied to the sample. For example, biobanks are collections of samples like blood, saliva and tissue, along with health data obtained from consenting adults.

Researchers use the samples to find links between our genes and disease, providing valuable information for the future. Organisations using biological specimens have an obligation to balance respect for participants with research benefits.

The recent film, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, tells the true story of an African-American woman whose cancer cells - code named HeLa - were taken without her knowledge in 1951. They were used to create a stem cell line, which had enormous clinical significance and commercial benefit in the decades since, but not for her or her family.

Lessons have been learned since then, and use of DNA without knowledge or consent would now be considered a shocking breach of legal and ethical principles.

Although research is needed to further knowledge, this cannot be at the cost of individual interests. Studies have shown that although individuals are happy to donate DNA samples, they may have concerns about how their samples are going to be used.

Sciences & Technology

Crime and privacy in open data

Informed consent is at the cornerstone of a robust research governance system. However, in genomic research, samples may be stored for unspecified and perhaps even unknown future use. How then can consent be truly informed?

Recent research may provide the answer. A Dynamic Consent model could satisfy the legal and regulatory requirements for research consent in this context.

This model provides a personalised online interface for interacting with patients, participants and citizens to inform them of how their samples may be used and to gain explicit consent for each use.

The UK RUDY (Rare UK Diseases of bone, joints and blood vessels) study is one of the first examples of a research project that has implemented a Dynamic Consent approach.

It’s a system that enables participants to have greater oversight and control over how their samples and data are used in research, and enables participants to tailor their levels of involvement and engagement.

So, while there may be different perspectives about who actually ‘owns’ our DNA, whether it’s us, our families or the broader community; being informed and transparent about how it is being ‘used’ is vital.

Any use of DNA deserves the utmost respect, underpinned by sound legal principles and governance.

HeLEX@Melbourne is a research team at Melbourne Law School focusing on health, law and emerging technologies, including issues such as consent, privacy and sharing of digital health data and human tissue samples.

Banner image: iStock