Why boys are blue and girls are pink

Hundreds of years ago the two colours told a very different story, but the current status quo will be hard to budge

Published 2 May 2016

Figuring out whether a stranger’s newborn is a boy or girl can be tricky. You’ve already started to frame a comment around how cute their baby looks when you suddenly don’t know whether to say she, he or, in desperation, it. To avoid that awkward moment, we often look for the universal clue – a splattering of pink for a girl, or blue for a boy.

But many centuries ago, this colour coding simply didn’t exist. Colours – particularly blue and pink – weren’t an indicator of gender, but rather caste and class.

“Colour in the Renaissance was very nuanced and symbolic, and this often reflected the cost and labour needed to source dyes and pigments,’’ says Dr Catherine Kovesi from the University of Melbourne’s School of Historical and Philosophical Sciences.

Back then, pink was a particularly treasured dye and pink cloth was often used as the first prize in horse races. And because it was expensive, pink was used by the male elite.

Go Figure: Six reasons reasons behind our love of chocolate

Go Figure: Why don’t humans have tails

“If you look at the images of the Renaissance … you will see the cityscapes populated with numerous men strutting proudly in pink clothes, and numerous male saints represented wearing pink as a way of signalling their station,” Dr Kovesi says.

Blue, specifically ultramarine, was also a prized pigment. Mostly sourced from present-day Afghanistan, it was made from ground lapis lazuli, which was a costly semi-precious mineral. From the 15th century this expensive pigment was often used for depicting the woman who most represented honour and virtue – the Virgin Mary.

Blue and pink now

Modern society’s associations with pink and blue have since switched the two around – pink for girls, blue for boys.

It’s also something that has happened relatively recently. Up until the early 20th century baby clothes were mainly neutral-coloured.

At the time, there was an emphasis on practicality – quick nappy changes and bleaching were important for working-class mothers who hand-washed clothing that was shared between multiple children.

It wasn’t until after WWII when pink for girls and blue for boys took hold.

“Men wanted their jobs back and governments encouraged women to return to their roles in the domestic sphere,’’ says Dr Erin Stapleton, an Honorary Fellow at the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies.

In western countries, it was a boom time for mass production, mass consumption and baby-making.

“The nuclear family is a very efficient unit through which the consumption of commodities is maximised,’’ says Dr Stapleton. Marketers focused on selling goods to families as autonomous units, which also had the effect of reinforcing separate gender roles in the household.

The easiest way to delineate gender roles from birth was through colours. “Dressing babies in certain colours produces rigid understandings of gender roles from an early age,” explains Dr Stapleton.

Dr Stapleton also says that women’s fashion and make-up of the 1950s also played a role. Generally speaking, what’s most attractive is what’s least achievable in a given society.

So coming out of a war, it’s not hard to understand the allure of health and vivacity. Make-up could help women look in the pink-of-health.

But with the abundance of pink stuff aimed at girls in department stores nowadays, you’d have to wonder where all this demand for pink is coming from.

Dr Lauren Rosewarne, from the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne, explains that girls and the colour pink have become so intertwined that many subconsciously buy into it.

“Into puberty and beyond when a girl is exploring her gender, most girls will elect to engage with femininity in varying degrees. In our culture, the default way to practice femininity is through appearance and, notably, the wearing of pink,” says Dr Rosewarne.

As it stands, as a result of this colour code, many young girls will seek out pink things to express their femininity, which fuels companies to produce and market pink items to girls, perpetuating the cycle.

It’s now impossible to separate pink as an expression of femininity from an advertising gimmick. So unless society as a whole can find other ways of recognising and expressing femininity, this blue-pink divide is here to stay.

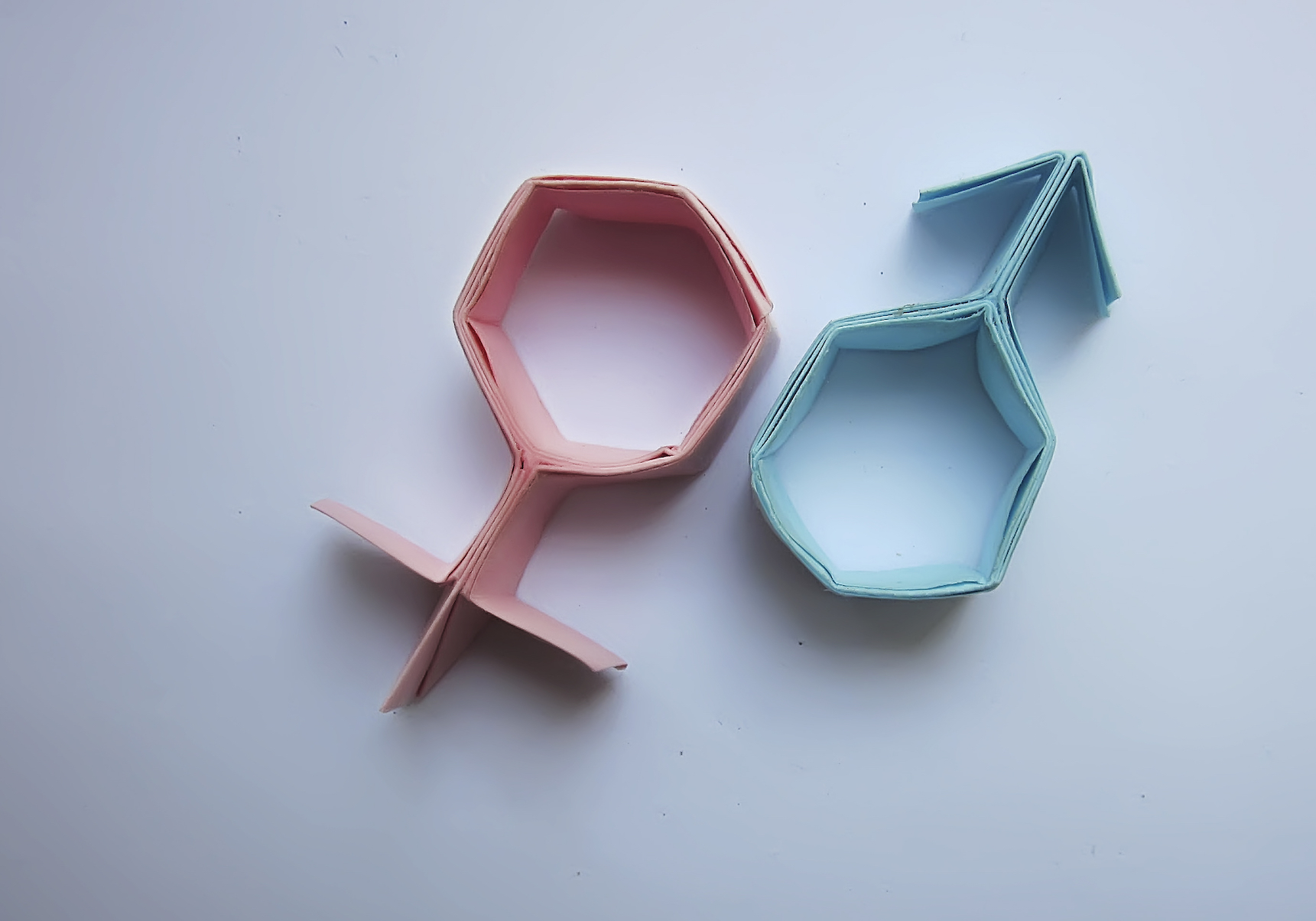

Banner Image: Male and female gender symbols, Ivan Erkhov/Flickr