Why Parliament should decide on same sex marriage

Changing the law sits with Australia’s MPs, not the people

Published 7 April 2016

As Australia faces one of the longest federal election campaigns in recent history, a key issue in the background has been the building momentum to legalise same sex marriage. So what is the best mechanism for change?

A plebiscite on same sex marriage will cost at least $160 million in direct costs and may come closer to $500 million in full costs according to recent reports.

This is not in itself an argument against holding one; every time we are asked to vote it comes at a cost but that is hardly an argument against democracy. In this case, however, it is not entirely clear why a plebiscite is considered necessary or appropriate to resolve the issue of same sex marriage.

is there a legal requirement to hold a plebiscite?

One reason that might justify the expense of going directly to the people is that it would be impossible to change the law to allow for same sex marriage without such a vote.

Some years ago that would have been a plausible argument; at least it would have been possible to say that a vote by the people was necessary to be sure that the Commonwealth has the power to legislate for same sex marriage.

The Commonwealth Parliament only has limited power to pass laws. Under the Australian Constitution, power is divided between the States and the Commonwealth and the Commonwealth can only pass laws with respect to specific areas set out in the Constitution.

Section 51 sets out many of those areas (sometimes called ‘heads of power’). Section 51(xxi) says the Commonwealth Parliament shall have powers to make laws with respect to ‘marriage’. Only the single word ‘marriage’ is used and it is not defined.

One question that might be asked is whether the use of the word ‘marriage’ in the Constitution – which is over 100 years old – could have been intended to include same sex marriage.

Those who drafted the Constitution, however, restricted themselves to a simple, single word and over time Parliament has fleshed out details such as the age at which people can marry, the circumstances that allow for divorce and so forth.

But that did not answer the question of whether same sex marriage was within the definition of ‘marriage’ for constitutional purposes. If that point had not been clarified, it might have been sensible to have had a referendum to change the Constitution to make it clear that the Commonwealth had this power.

However, in 2013 the High Court clarified the issue in a case that determined the ACT Marriage Equality (Same Sex) Act 2013, which allowed same sex marriage, was invalid. In its reasoning, the court determined that same sex marriage was within the definition of the word ‘marriage’ in the Constitution.

There is therefore no legal reason to require a vote of the people to clarify this situation. It is clear that the Commonwealth has the power to pass a law allowing for same sex marriage.

But isn’t it a good idea to ask the people for their views?

The Australian Constitution creates a ‘representative’ form of government. We vote for parliamentarians to represent us and those parliamentarians thrash through the details of what laws should be passed, in what terms, with what trade-offs and consequences. Given the complexity of modern society, any other system would be untenable.

There is, however, an element of direct democracy introduced by our Constitution which, under section 128, can only be amended by a majority of voters in a majority of States.

So if parliamentarians wanted to introduce a Republic, or change the balance of federal power, or abolish the Senate, or limit the powers of the courts, they would first need to seek the permission of the Australian people in a referendum.

This means that the basic structures of our democracy remain in the hands of the people but the day-to-day decision-making is delegated to elected representatives. The reason that the same sex marriage vote is being described as a plebiscite and not a referendum is that it does not require a change to the Constitution; all that is needed is a change to the Marriage Act.

While the political pressure for parliamentarians to respect the results of a plebiscite is considerable, in legal terms this is only a very large opinion poll; that is the reason that some parliamentarians could say that they would not vote for same sex marriage whatever the result of the plebiscite.

It would not be an inherently bad thing to ask the views of the Australian people about a range of issues. This has not, however, been a part of the political culture in Australia.

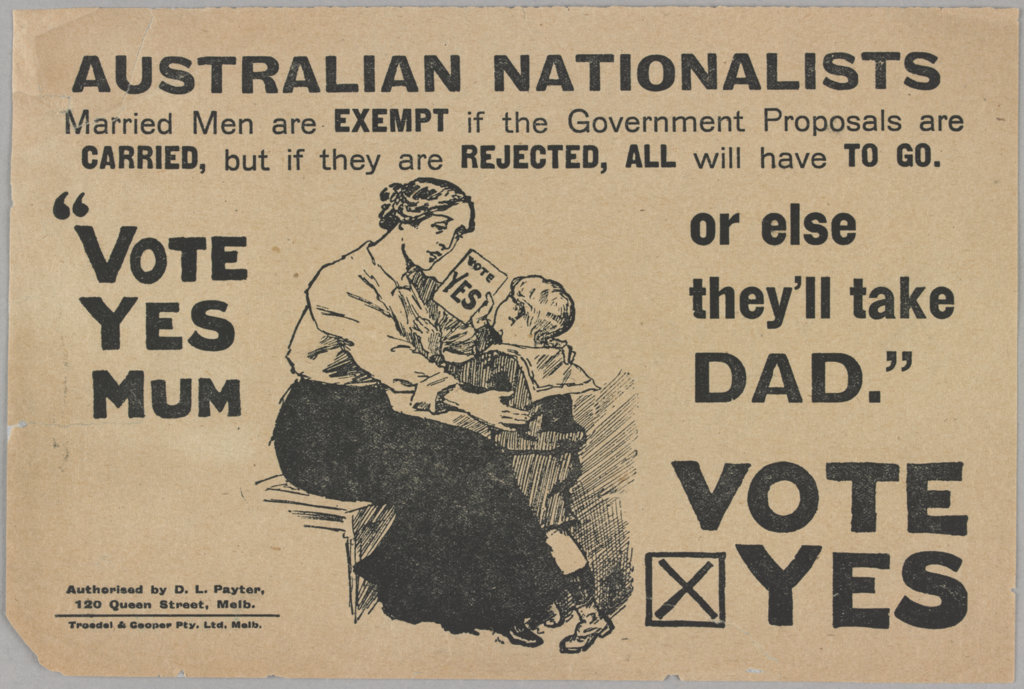

There have only been three Commonwealth plebiscites since Federation – two about conscription and one on changing the Australian anthem. In recent decades there have been none.

Australian parliaments have never shied away from controversial laws or issues that divided the public (including on religious or moral grounds). On the contrary, Commonwealth and State parliaments have passed laws on everything from terrorism to no-fault divorce to anti-discrimination laws to abortion to capital punishment.

In the general community, some people strongly supported legal changes in these areas, some strongly opposed and many were indifferent.

If people felt passionately enough about a matter they lobbied their local members or held protests or wrote petitions or voted for someone else in the next election – all the usual ways that people seek to influence politicians in a representative democracy.

Same sex marriage is very much in this category. In comparison to some issues, same sex marriage is not even particularly controversial with a fairly substantial majority of Australians supporting the change in most opinion polls.

There is nothing within our laws or Constitution to prevent holding a plebiscite either.

If politicians decide that they want to shift their usual burden of making such decisions to ordinary Australians they can do so. But the question remains – what makes same sex marriage so special that it should be taken directly to the people rather than voted on in parliament?

Parliamentarians should have the courage of their convictions (whatever those convictions may be) and bring the matter to a vote of the parliament rather than trying to delegate their responsibilities to a society where a strong majority have already expressed their support for a change in the law.

Banner image: Shutterstock