Arts & Culture

To be or not to be ... original

As Melbourne hosts the world’s first full-scale working replica pop-up of one of the greatest theatres in history, the second Globe, we explore what the Bard would make of it

Published 17 September 2017

Would Shakespeare approve of the Pop-Up Globe in Melbourne?

Of course he would. The first ‘pop-up Globe’, after all, was The Globe itself.

Shakespeare’s company had been performing at the imaginatively named The Theatre in Shoreditch, to the north of London, when their lease expired. The land was owned by one Giles Allen, but the physical premises were owned by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

Sometime around 28 December in 1598, the company’s leading actor, Richard Burbage, along with his brother Cuthbert Burbage and several others, began dismantling the physical structure of The Theatre and carried “all the wood and timber therof unto the Banckside in the parishe of St. Marye Overyes, and there erected a newe playehowse with the sayd timber and woode”. This, according to a lawsuit involving the Burbages and Allen in 1602.

Arts & Culture

To be or not to be ... original

The new playhouse they built was the first Globe Theatre; according to popular tradition, it popped up overnight (though in reality it probably took closer to six months to assemble).

The original Globe was the venue for King Lear, Othello, Henry V, Hamlet and most of Shakespeare’s mature plays.

In 1613, however, it burned down during a performance of Shakespeare and John Fletcher’s play, Henry VIII, or All is True, thanks to a pyrotechnics disaster.

Cannon fire flared and “the fire catched and fastened upon the thatch of the house and there burned so furiously, as it consumed the whole house and all in less than two hours” according to a contemporary report.

A second Globe Theatre (after which the Melbourne theatre is modelled) was built immediately to replace the original; the new playhouse was said to be the fairest in England, and it stood until the English Civil War.

Melbourne loves a good pop-up Shakespearean theatre.

When the English comedian George Coppin arrived in Australia in 1843, he became a theatrical entrepreneur. During a visit to the United Kingdom, he persuaded the star Anglo-Irish Shakespearean actor Gustavus Brooke to come to Australia and New Zealand on a tour numbering 200 shows.

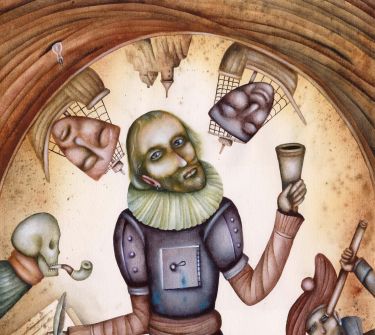

For this celebrity tour, Mr Coppin ordered the construction of a new theatre as a showcase specifically for Mr Brooke. The Olympic Theatre – known informally as the Ironpot because it was “a prefabricated theatre made of cast-iron, corrugated iron, timber and glass”.

Unfortunately The Olympic, on the south-east corner of Lonsdale Street, wasn’t ready at the time of Gustavus Brooke’s arrival, but Mr Coppin’s career survived, and he went on to become a Member of Parliament out of the desire to prove that actors could be useful members of society. He was also responsible for the first hot air balloon ride in Australia, and recreated the Battle of Sebastopol in his Cremorne Gardens in Richmond, for those who were unable to see the historical event in person.

In February-March 1969, during Melbourne’s Moomba festival, the then-uncovered area of the Keith Murdoch Court of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) was turned into a kind of Globe Theatre of Richard Prins’ imagining for a Melbourne Theatre Company production of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1.

The NGV was the first part of the Victorian Arts Centre development opening in 1968, and the Melbourne Theatre Company’s outdoor performance predated the opening of the Melbourne Concert Hall in 1982 and eventually the theatres in 1984.

This production of 1 Henry IV was thus the first live production of a play at the Victorian Arts Centre. British actor Raymond Westwell played Henry IV, Australian Frank Thring played Falstaff, and the founder of the Melbourne Theatre Company, John Sumner, directed.

The current Pop-Up Globe is specifically intended to be temporary, and does not attempt to recreate original materials and assembly methods in the manner of the current Globe Theatre in London. The modern Globe opened in the mid-1990s and used sixteenth-century wood-cutting practices and lime plaster made according to instructions that were current in Shakespeare’s lifetime.

It’s described “as faithful to the original as modern scholarship and traditional craftsmanship can make it” but still, it remains a “best guess”.

By approximating the dimensions and technologies of the early-modern playhouse, the modern reconstruction on the Thames purports to offer a space for performance-based research and experimentation in early staging conditions.

The University of Western Australia has a similar experimental space, their New Fortune Theatre, modelled on the precise dimensions of the Fortune Playhouse in Golding Street, London – home to Shakespeare’s chief rivals, the Lord Admiral’s Men from 1600.

Arts & Culture

Why Shakespeare still matters

In the US, a crowd-sourcing campaign is raising money to build a Globe Theatre in Detroit made entirely out of repurposed shipping containers. Like the Melbourne Pop-Up Globe, the point is not to recreate the material conditions of Shakespeare’s day, so much as to capture the essence of attending a Shakespearean play in an environment that makes the audience feel part of the action, to feel as though their relationship with the actors mirrors the experience of those early playgoers.

There is an undeniable thrill about seeing one of Shakespeare’s plays come to life in a space that resembles the bear-baiting arenas, the ribald amphitheatres or lively playhouses of Shakespeare’s day.

Attempts at recreating historical buildings can be fraught with challenges, but pop-up theatre spaces that attempt to recapture the spirit of early theatres are a very different proposition.

What could be more Shakespearean than embracing the entrepreneurship of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1599 and assembling a Globe for Shakespeare’s plays to be enjoyed?

Banner image: Wikimedia