Business & Economics

The lessons from past pandemics

A spectre is haunting the world but it isn’t COVID-19, it’s the idea that the pandemic could lead to the end of globalisation

Published 16 May 2020

Great catastrophes of history have always stimulated human imagination, but the current pandemic has exacerbated levels of speculation and transformed some intellectuals into fortune-tellers.

Recently, British political philosopher John Gray declared the “era of peak globalisation” over and predicted the fall of governments.

Gray says that COVID-19 will mean that “people travel less”. And that the European Union will decline “like the Holy Roman Empire” as it becomes dominated by the extreme right and falls under the growing influence of Russia.

According to Gray, the world order will fall apart.

He depicts “de-globalisation” as the offspring of globalisation and says it is already underway. There is no choice but to adapt to a future where Western countries are ill-prepared, but some Asian countries will thrive.

Business & Economics

The lessons from past pandemics

However, these predictions about an emerging new historical era are not based on evidence or precedents. A basic tenet of science - that arguments need to be based on facts - seems to be overlooked these days.

American political scientist and economist, Francis Fukuyama predicted the end of history in 1989, and the allegedly unavoidable global triumph of capitalism and liberal democracy.

Now we are told we are not witnessing the end of history, but the dawn of a de-globalised world.

There is intense historical debate as to when globalisation began.

For many, it started in the late nineteenth century, when technologies like the telegraph, railway and steamship connected the world and its markets.

But American sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein dated the onset of globalisation to the 16th century when European expansion connected the world and created the first economic system with centres and peripheries.

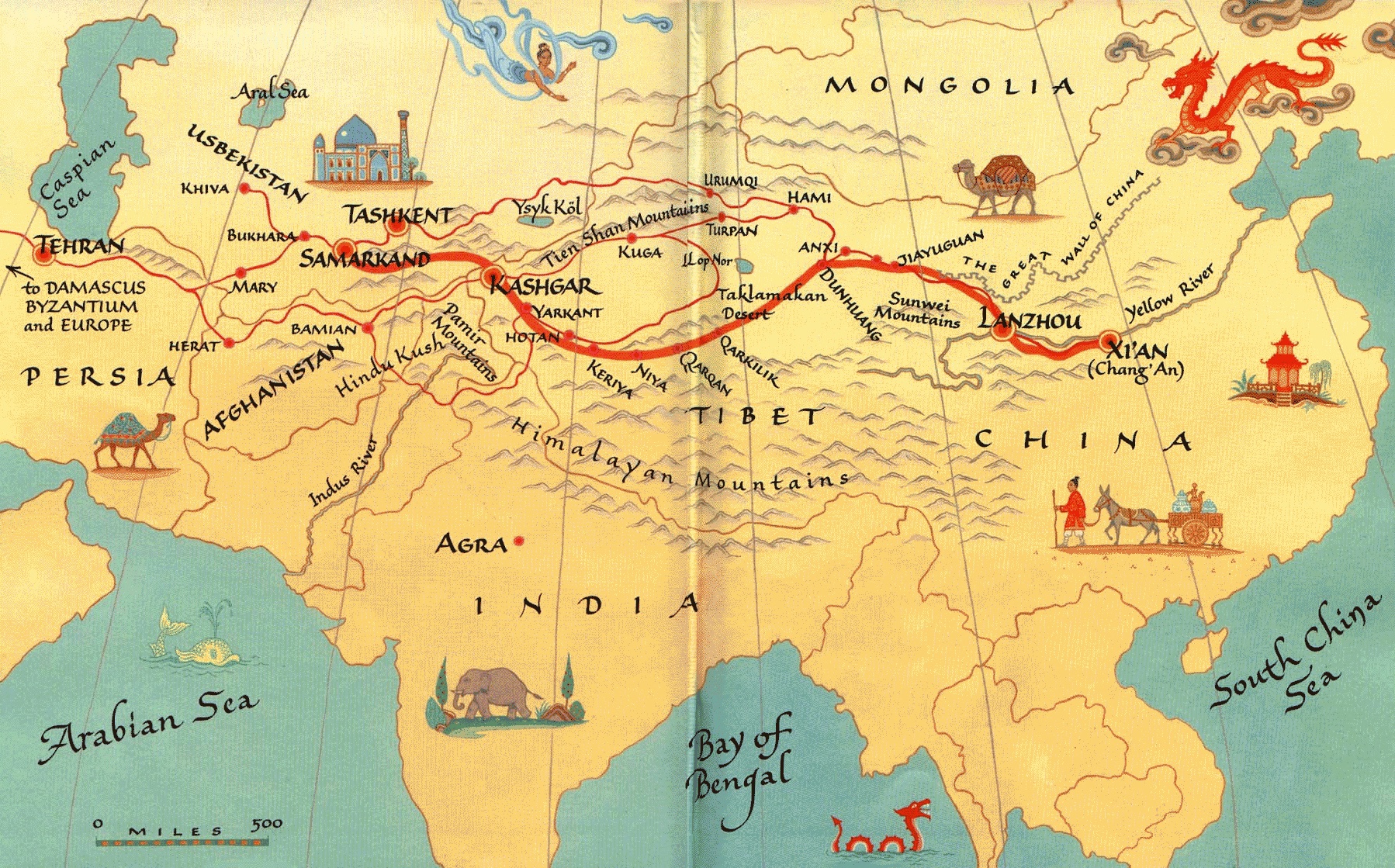

Another American sociologist, Janet Abu-Lughod, argues that we can trace global economic linkages back to the 13th century, while others push this back even further to the year 1000 or even 3000 BCE.

Arts & Culture

How have plagues and pandemics influenced the arts?

If we take the 16th century as the starting point, we present globalisation as the heroic accomplishment of Europeans who explored the Oceans. Tracing its beginning back to the 19th century sees globalisation as a by-product of the expansion of the British Empire.

Other research focuses on the opening of the trans-Pacific route connecting the Spanish colonies of the Americas to the Far East, highlighting the crucial role of the Chinese economy due to its enormous demand for American silver.

More recently, the 16th and 17th century Iberian Empires highlighted the role of Mexican, Brazilian, African and Indian actors in cultural globalisation. And in the 20th century, it’s characterised by rivalry between capitalism and socialism, the Soviet Union led “red globalisation” that challenged the world liberal economy.

The relationship between disaster and globalisation is complex.

Look at the impact on the globalisation process of events like the bubonic plague, the incorporation of America and the World Wars. Their consequences disprove those who prophesise globalisation’s end.

The bubonic plague decimated the European population in the 14th century. Interestingly, several witnesses attributed this to the ‘globalisation’ of the day.

Arts & Culture

Journal of the plague year

Arab historian Ibn al Wardi, an eyewitness to this plague as it devastated Aleppo, pointed to the Far East as the origin of the disease that travelled along the Silk Roads. The losses caused by this pandemic far outnumbered the current losses.

Even though commercial connections with the Far East were perceived as the cause of the disaster, people living in the 14th century did not want to renounce the pleasures that early globalisation provided.

Moreover, the Europeans’ longing for the Far East was the basis for an unprecedented acceleration of globalisation as the Americas joined commercial and biological exchanges with the Old World.

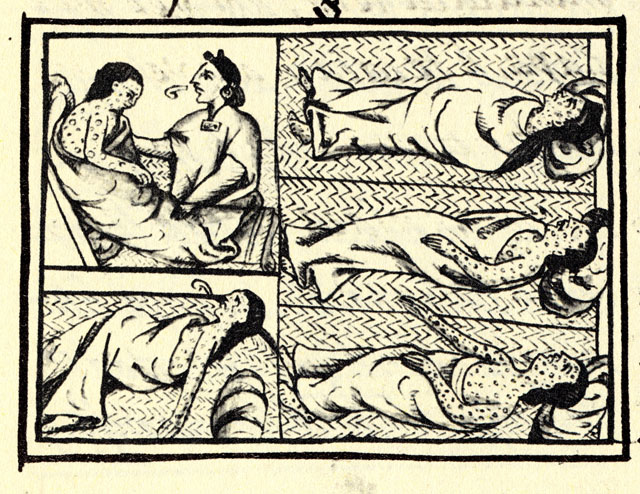

The arrival of conquistadores to the New World was devastating for the local population as they carried pathogens acquired from their global epidemiological history.

The subsequent demographic disaster accelerated the biological globalisation that shaped the current world.

Huge population losses were replaced with a massive inflow of slaves from Sub-Saharan Africa. Access to the American silver mines energised Asiatic manufacturing and triggered a series of regional commercial exchanges of textiles and spices from the Indian Ocean.

But these side effects – positive or negative – were determined by of an array of actors who benefitted from opportunities provided by an increasingly interconnected world.

Arts & Culture

How plague helped make Rome a superpower

Only if we adopt a narrow economic view of globalisation that exclusively focuses on its economic dimension is it possible to consider that catastrophes, conflicts and crises may ‘interrupt’ the phenomenon.

But this view produces a vision of globalisation at odds with its reality.

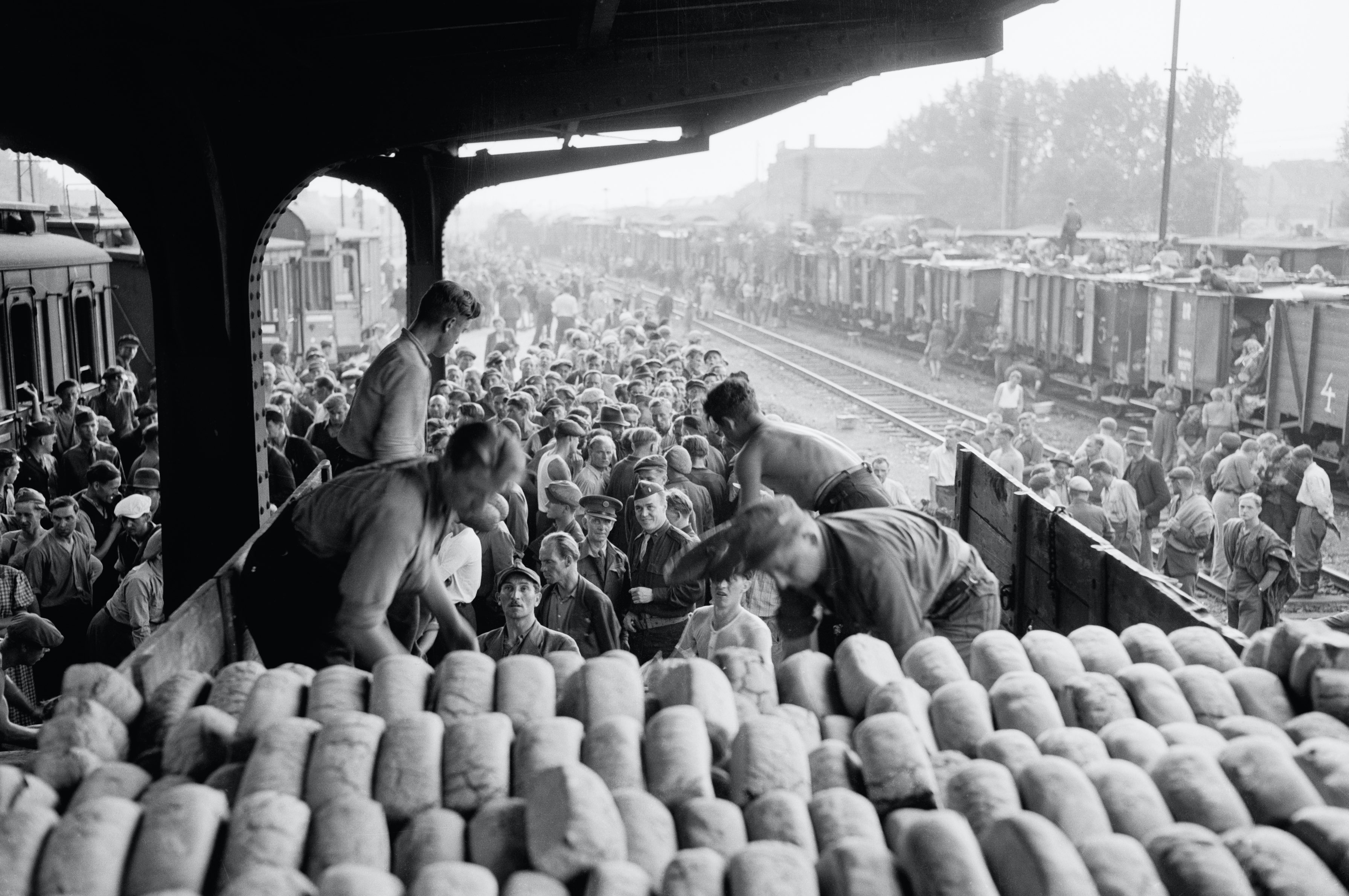

While the Great War did divide Europe, disrupting international trade and migration, it was a globalising event. Events on the western front had immediate effects in remote parts of Asia and Africa where colonial empires clashed.

African soldiers were deployed in the European battlefields and tens of thousands of Chinese workers were sent to the Old Continent to help the Allies’ war effort.

The global circulation of soldiers accelerated in World War II and millions of men and, to a lesser extent, women discovered new parts of the planet and new cultures. They became conscious of their shared human condition in a more interdependent world.

Military technological developments also contributed to the acceleration of global interdependence.

The American flying fortresses, the B-29, inspired the development of transcontinental airplanes.

Arts & Culture

Isolation, my Dad and me

Between wars, the rise of nationalism and fascism implied a return to economic protectionism and the collapse of international trade. But, this did not interrupt globalisation.

New socioeconomic models, like authoritarian corporativism, circulated globally. Ultra-nationalism did not mean less global interconnection – it saw interrelations become more conflict-prone, violent and dangerous.

This triggered population movements on a global scale.

At the same time, humanitarian aid led to increased international activity through governmental organisations like the United Nations, as well as non-governmental organisations (NGO).

The 20th century was “a century of NGOs”.

The geopolitical division of the Cold War also implied intense global interaction motivated by the threat of nuclear war and by the universalist projects of the US and the USSR.

History demonstrates the dynamism and resilience of global connections despite the very catastrophes that globalisation provoked.

In the light of past experiences, it would be risky to predict deep transformations or the renunciation of interconnection and interdependence.

The COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t mean the end of globalisation; it doesn’t even mean the beginning of de-globalisation. One thing is certain though – global interdependence will continue as a defining feature of our time.

A version of this article was originally published in Spanish on the ES Global website as El coronavirus pondrá fin a la globalización?

Banner: A medieval world map called the Catalan Atlas/Wikimedia