Sciences & Technology

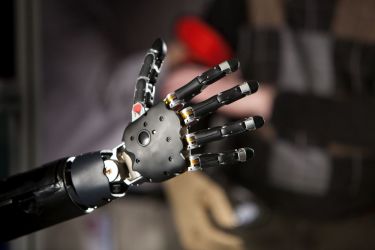

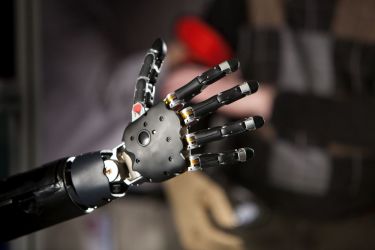

Rise of the robots

As autonomous technology becomes a part of every-day life, what impact will they have on where we live and how we work?

Published 9 October 2017

As the world’s population grows and the revolution in how humans live and work proceeds at accelerating pace, the cities that are home to many of us are becoming larger and more complex.

As is our infrastructure.

“A mid-20th century system is not going to deliver for a mid-21st century environment,” warns Mark Stevenson, Professor of Urban Transport and Public Health at the University of Melbourne. The internationally recognised expert on transport safety and public health says he is worried by the problems he sees – here, and abroad.

Of these, transportation is a lynchpin, likely to have far-reaching impact on human health, quality of life and social cohesion.

“Australia has major challenges in relation to planning transport infrastructure,” Professor Stevenson says. “We are not delivering what is needed.”

It’s the arrival of autonomous vehicles across the transport network within 20 to 25 years that could compound the issue.

“Bringing with it a level of complexity not yet seen, with vehicles that will operate in a system that hasn’t been designed for them,” says Professor Stevenson.

Driverless or remotely controlled transportation is already common in many industries. Australian iron ore and coal mining use remotely controlled trucks, as do some airport and inner-city railways; for example, very high-speed autonomous trains service Shanghai Airport.

Sciences & Technology

Rise of the robots

But driverless vehicles are not yet on public roads. And their integration with existing systems as well as human drivers, presents a challenge for urban and social planners.

There are both negatives and positives flowing from the incorporation of driverless vehicles into our everyday lives and the way we work, according to Professor Stevenson.

“Autonomous vehicles will provide greater efficiency in transport; on-demand ride sharing could reduce the number of cars on the road, though traffic could also increase,” he says.

With driverless vehicles, he says, patterns of commuting will change.

“We are doing some exciting work looking at 1700 cities, each with populations of more than 300,000. Cities that are car-dependent, like Melbourne, certainly cluster. Those cities spread because they grew when ‘car was king’.

“This opened land on the fringes of the city for housing. It was cheaper and it was populated usually by people of lower income, but it was often developed without adequate planning of infrastructure.

“So, we are seeing greater inequities in our outer suburbs because of that.”

The implications of these developments have been far-reaching, both on our lives and our lifestyles.

“Employment does not seek you where you live; you find it where you can,” says Professor Stevenson. “There have been major increases in travel, particularly for those lower income groups – sometimes three or more hours daily. As a consequence, there are significant health effects including major implications for cardiovascular systems, stress, social isolation and mental health.

“Introducing autonomous vehicles for such areas would be positive, but they would need to be integrated into a modern public transport system. It will give people living in outer parts of the city access to an amenity they have never had, but the cost has to be reasonable.”

Planning and careful policy-making will be critical for getting the maximum health benefits out of this new phase of transportation.

“We need to build active transport into our daily lives,” says Professor Stevenson.

“We need to ensure that people can walk to public transport, or take their bikes on it so they can use them to continue their journey. If we design it in a futurist way we potentially will get health benefits – a bike rack on the back of the autonomous car, for instance, or an autonomous vehicle that takes you to a public transport node.”

So what about dispersal of employment away from city CBDs? Making that work will be the challenge for urban planners, engineers and legislators, as much as for social scientists and health professionals.

“We know that, in relation to what we refer to as new urban mobility, planners are saying let’s incentivise public transport. To do that, they have to put a barrier around the city for vehicles, such as high parking charges or congestion charges as we’ve seen in London, Helsinki and Copenhagen,” suggests Professor Stevenson.

“One big plus would be an incredible reduction in a city’s carbon footprint. Global energy use in urban transport could be cut by more than 70 per cent with savings of $5 trillion a year.”

Professor Frank Vetere, Director of the Microsoft Research Centre for Social Natural User Interfaces at the University of Melbourne’s Department of Computing and Information Systems, says that while the march of technology – whether it be the advent of driverless vehicles or other advances in automation – is unstoppable, humans will need to be equipped to make key decisions and drive change in their favour.

“Anything that can be automated will be, but the human side will always be important. That’s the most important thing, really, the parts that cannot be automated; our humanity,” Professor Vetere says.

In his view, artificial intelligence’s capability to make humanlike, sophisticated decisions and judgments is “a very, very long way off”.

While technology has brought great improvement in productivity, “we are still wasting a lot of time finding passwords and files and dealing with systems that fail,” he notes.

“People talk about all the things technology is going to do, but they don’t talk about how it is going to rely more on human-type senses: how it might look where you are trying to anticipate your actions, relying more on humanity than less. And that could bleed off into society and make it better; at least, I hope so.”

Banner image and video: Getty Images