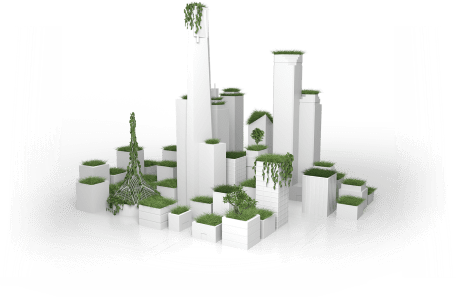

Growing greener cities

Planting gardens on office buildings will reduce inner-city temperatures and create energy savings - and improve workers' moods.

Published 29 October 2016

On a hot, sticky day, air conditioning is a modern-day miracle. But its side effects are not: drying skin, increased noise and even the possible spread of infections.

And it’s expensive.

But planting vegetation on a building’s roof has lots of upsides: naturally cool cities and reduced energy costs. Green roofs can be minimally planted with succulents and native grasses or lush with bright fruit trees and flowering perennials, but be just 10cm deep. And the benefits are numerous: reduction in stormwater run-off, natural shading and cooling, lower energy costs and even psychological benefits, such as increased concentration and productivity.

The University of Melbourne is a leader in researching and implementing green roofs, which are set to become part of Melbourne’s booming skyline.

Dr Claire Farrell, lecturer in green infrastructure in the School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, says: “In Melbourne, we’re going through a period where we’re building lots of apartments close to transport hubs and green roofs are a way of fixing environmental problems, with lots of other benefits.”

There are two types of green roofs: extensive, which are quite shallow and contain low-maintenance plants such as hardy succulents and grasses, and intensive, which are deeper and can include more variety in greenery, including vegetables, shrubs and even small trees.

The vegetation and soil shades hard, impervious materials such as bricks and concrete, which in turn reduces the absorption of heat from the sun and provides natural cooling.

University of Melbourne researchers released the Growing Green Guide, an industry-standard manual, which explains the science behind the concept.

The manual, which is available free online, says that evapotranspiration – water released from soil and plants and released through leaves – takes the sun’s energy for that process, which would otherwise have increased air temperature.

Choosing the right plant for a green roof is essential. Unlike in other parts of the world, where the winters are much colder and rain is heavier, Melbourne’s summers are often hot, dry and long but our winters are warmer and wetter.

Dr Farrell has explored the most suitable plants, which come from ecosystems that are naturally like green roofs, such as rock outcrops.

Dr Farrell and Associate Professor Nicholas Williams, also from the School of Ecosystems and Forest Sciences, have looked at some of Victoria’s endangered native grasslands, which are low maintenance and can cope with spikes in hot weather.

Associate Professor Williams is part of a team trying to quantify the financial savings, but says early research suggests it could be about 30 per cent.

“The savings depend on the type of building. If it’s a high-rise, the insulating effect of the green soil and plants will mainly benefit the people on the floors directly below the roof,” Associate Professor Williams says. “But putting green roofs on lower buildings, or the podiums of office towers, will also cool more people on the street.”

As cities have developed, we’ve replaced all the natural vegetation with bitumen and those hard surfaces really heat up and make cities hotter.Dr Claire Farrell, lecturer in green infrastructure in the School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences

Dr Farrell, who co-runs an Australian-first research green roof at the University’s Burnley campus, in Melbourne’s inner east, says the convenience of urban living has created a phenomenon called urban heat islands, which is caused when hard materials trap and increase heat.

“As cities have developed, we’ve replaced all the natural vegetation with bitumen and those hard surfaces really heat up and make cities hotter,” she says.

Increasing population and construction, cars and industry are all contributing to making Melbourne’s temperature rise. And the hotter it gets, the higher the likelihood of residents getting heat stress and other heat-related health problems.

There is also the problem of stormwater and pollution.

“We get problems like flooding when there’s too much rain, because that water has nowhere to go. And because it runs off buildings and roads, that water picks up pollution and degrades the natural ecosystems,” she explains.

But if more green roofs are installed, Dr Farrell says, the plants will absorb much of that water and prevent it from polluting the environment.

While green roofs are still a relatively new concept in Australia, there are many cities overseas that have embraced the technology. Berlin and Copenhagen are among the leaders, where installing one is as cheap and easy as “going to Ikea”, Dr Farrell says.

But while Melbourne is lagging behind, our climate, booming population and building works are the ideal conditions to join other innovative cities.

“Because we’ve created green roofs just for Australian and Melbourne conditions, our system is a lot more sophisticated than if we had just copied what was being done mostly overseas,” Dr Farrell says.

While the financial pay-offs for lower energy costs and reduction in the chance of floodwater are important for infrastructure, the benefits to people’s mental health are just as powerful.

Those benefits have been researched over the years, proving that workers who have access to some form of nature perform better throughout the day.

The University of Melbourne last year released the findings of its research into productivity from workers who took a ‘micro-break’ of just 40 seconds looking at vegetation.

They found that those who glanced at a green roof boosted their concentration and increased their performance for the rest of the day.

Green roofs are a truly interdisciplinary area of research: while science is at the heart, experts from across architecture, psychology, engineering and business are also involved.

Dr Dominique Hes, director of the Thrive Research Hub at the University’s Melbourne School of Design, says load bearing and maintenance are the two biggest issues when incorporating a green roof into building plans.

“If it’s a retrofit, we look at whether the building has the structure to support the extra weight, including when it rains, because the water will add weight,” Dr Hes says.

There are approximately 50 roof gardens across the Melbourne CBD and more are expected as the skyline becomes increasingly crowded with high-rise buildings.

Melbourne City Council was one of the first local governments to adopt a green roof policy, and encourage building owners to include one in their plans or retrofit an existing building.

Gail Hall, who leads the council’s team in open space planning, says there are 880 hectares of available space on Melbourne’s rooftops.

“The potential is amazing,” she says. The key motivation for developers to include a green roof is marketability and creating a point of difference, she says.

“They want to make their buildings the most appealing and increased vegetation in the city is one of those ways.”

But how should we encourage developers to include green roofs? Should we change planning laws and overlays or is public education the answer?

Dr Farrell believes that if you made green roofs compulsory for mid-rise and high-rise buildings, then developers would be tempted to install them “on the cheap”.

“Instead, I think we’ll probably get to the point in which people will demand them. If you have the choice between living in a building that has a beautiful roof garden and one that doesn’t, that might be the deciding factor for buyers and renters.’’

Find out more about this research.